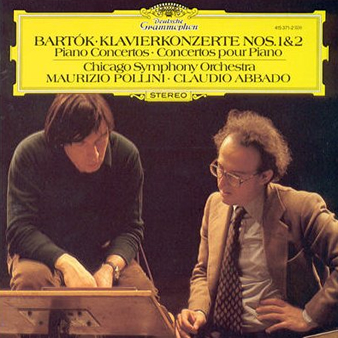

Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 1

Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 2

Maurizio Pollini, Piano – Chicago Symphony Orchestra (Claudio Abbado, Conductor) (Deutsche Grammophon)

Recorded: Chicago, Orchestra Hall, February 1977

ONE-SENTENCE REVIEW:

After nothing but a diet of Bach for the past couple of weeks, a little Bartok at his chaotic best is just what the doctor ordered – this is an excellent recording.

ORIGINAL LINER NOTES (by Paolo Petazzi – translation, Gwyn Morris):

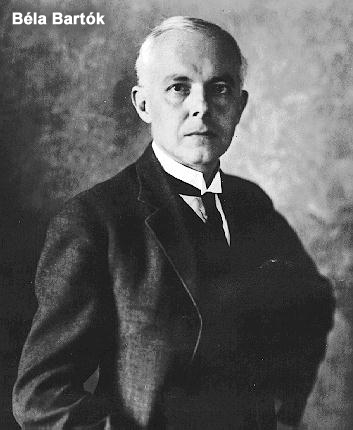

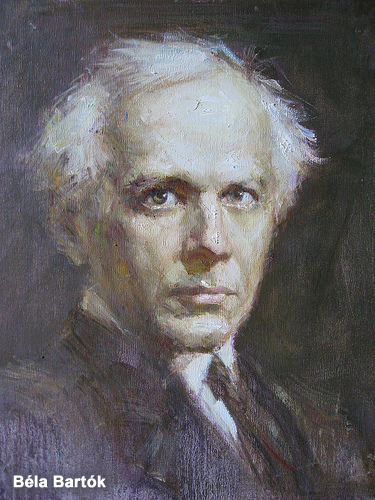

Bela Bartok’s first two piano concertos, dated 1926 and 1930/31, belong to two different stages of the period when he was formulating the musical language of his advanced maturity – a synthesis in which an original reassessment of certain aspects of the European cultural tradition (Bach, Beethoven, Debussy) combined with stimuli and influences resulting from the study of Hungarian and Balkan folk music: in assimilating rhythmic and melodic elements foreign to Western classical music, Bartok did not use them in an ornamental, “exotic” way but as an integral part of a new language.

Concerto No. 1, composed between August and November 1926, immediately follows other important piano works like the Sonata and the “Out of Doors” Suite, to which it bears a strong affinity; these works mark a revival of Bartok’s creative activity after three years of almost total silence.

Concerto No. 1, composed between August and November 1926, immediately follows other important piano works like the Sonata and the “Out of Doors” Suite, to which it bears a strong affinity; these works mark a revival of Bartok’s creative activity after three years of almost total silence.

In a famous statement he made to the musicologist Edwin von der Null, Bartok himself stressed the presence of new stylistic characteristics in the Sonata and the First Concerto, pointing out the fruits of his interest in Baroque music, such as a more striking use of counterpoint than was apparent in his previous compositions.

Concerto No. 1 can also be seen as Bartok’s personal response to certain trends in the 1920s, from neo-classical objectivism to the vogue for solid construction and Bachian counterpoint. But Bartok’s style remains alien to the ironic taste for “pastiche” and “square-cut music”: in its harsh, severe, rigorous conception, Concerto No. 1 reveals a unity and force that are quite singular.

In the solo part, the more strictly percussive aspects of Bartok’s piano style predominate in a quest for violent sonorities, biting harshness, combinations of sounds conceived more as blocks than chords in the traditional sense.

And already in the First Concerto this type of piano writing spurs Bartok to probe the potentialities in the relationship between piano and percussion: in this respect there are clear anticipations of the Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion (1937).

The use of ostinatos, insistent motor rhythms sustained by constant propelling energy, are what chiefly link the Concerto to other experiments of the ’20s; but Bartok’s way is a highly personal one, a deliberate choice of discourse in the first person (and thus poles apart from Stravinsky and neo-classicism).

The balance between soloist and orchestra, only theoretically akin to that of the Baroque concerto, is brought about within a severe conception in which the orchestral colour is mainly sober and tends more to an essential chiaroscuro (excluding, therefore, innovations in sonority) than to a wide variety of colour, in keeping with the compact form of the entire work, its obsessive unity and the violent, barbaric energy which bursts forth from the harsh, hammering writing.

In the introduction to the first movement, which immediately defines some essential characteristics of the music, there emerges a basic melodic cell to which a great part of the material of the composition is related.

In the introduction to the first movement, which immediately defines some essential characteristics of the music, there emerges a basic melodic cell to which a great part of the material of the composition is related.

Immediately after the introduction, the soloist states the first theme, the only one which stands out strongly in relief; those that follow are less broad and more like brief thematic nuclei. Hence, even if one recognizes in the first movement sonata-form construction (exposition-development-recapitulation), the logic which determines it is profoundly different from the Classical conception, in its combining and elaborating of the thematic material within a closely-knit, contrapuntal web and its frequent use of the ostinato technique.

The Andante, where the strings are silent, begins with a dialogue between piano and percussion. New and subtle relationships of timbre in this austere meditation open up regions of astonishing originality and profundity.

In the central section of the Andante, clearly constructed in A-B-A form, the piano repeats an ostinato figure which acts as a background to a crescendo traced by the woodwind. A brief transition with grotesque trombone glissandi links the second to the third movement, which is more animated and lively throughout.

A string ostinato accompanies the statement of the first theme; the successive ideas which support a structure tending to the episodic are all variations of a single nucleus. It is possible to detect connections between the thematic material of the first and the third movements, even though these are not constructed systematically as in Concerto No. 2.

In an article which appeared in 1939, Bartok wrote: “My First Concerto… I consider it a successful work, although its style is up to a point difficult, perhaps even very difficult for the orchestra and the public. And so I decided, a few years later, in 1930/31, to compose my Second Concerto with fewer difficulties for the orchestra and more pleasant themes. This aim of mine explains the more popular and easier character of the greater part of the themes…”

This statement should not be taken too literally, but it points to the different style of the two concertos. In the roughly five years that separate them, Bartok had written, among other works, masterpieces like the Third and Fourth Quartets and the Cantata profana, and their proximity is discernible in the inspiration of the Second Concerto.

This statement should not be taken too literally, but it points to the different style of the two concertos. In the roughly five years that separate them, Bartok had written, among other works, masterpieces like the Third and Fourth Quartets and the Cantata profana, and their proximity is discernible in the inspiration of the Second Concerto.

Here, there are certainly no compromising concessions to “easy music,” but it is true that the thematic material presents a more clearly recognizable profile and the quality of expression is more fluid in comparison with the harsh tension of the First Concerto.

Similarly, the orchestral writing provides a greater variety of colours, more lively and vivid – especially in the third movement, the only one in which the whole orchestra is featured (in the first movement, the strings are silent; in the Adagio, the woodwinds are excluded from the first and third sections).

The relationship between soloist and orchestra is also one of slightly less rigorous integration, allowing space for cadenzas in the first movement. The overall construction of the Second Concerto is similar to that of the Fourth Quartet: the first and third movements, with their internal similarities, are symmetrically placed around the central movement, which itself has a ternary construction – Adagio-Presto-Adagio.

In the Allegro, the first theme is obviously inspired by Stravinsky: the melodic shape of the first notes corresponds to the beginning of the horn theme at the start of the finale of The Firebird. Other analogies can be drawn with Petrushka. Such occasional affinities can also indicate how differently Bartok and Stravinsky – in his Russian period – used popular themes.

In Bartok, we note an underlying sense of moral conviction, of familiarity bred of a long and intense study of folk music – in other words, an involvement leading to results far removed from those produced by Stravinsky’s dry stylization.

In Bartok, we note an underlying sense of moral conviction, of familiarity bred of a long and intense study of folk music – in other words, an involvement leading to results far removed from those produced by Stravinsky’s dry stylization.

In any event, Bartok turns to advantage in a most personal way the “Stravinsky” theme in the Second Concerto.

In the sonata-form construction of the first movement (where the recapitulation presents the inversion of the themes in the exposition), there is a lavish variety of invention and modes of expression.

The Adagio is another specimen of “night-music” based on a completely different range of timbres from that of the Andante in Concerto No. 1. In a kind of tense and mysterious dialogue, we hear by turns a slow-paced chorale rendered by the pallid sonorities of the strings and the meditative comments of the piano with arabesques of intense evocative force.

After the first Adagio, a real Scherzo (Presto) leaps into action, light and pungent, with extreme and fantastic mobility; then, the opening episode returns and the Adagio fades away in an atmosphere of uncertainty.

In the third movement, the first theme – with its incisive energy, its hammering, barbaric force – seems to lead back to the mood of the First Concerto.

It is the only really new thematic element in this section, and acts as a refrain whose appearances frame the other episodes, all based on variations of the thematic material in the first movement (it is not difficult, on listening, to recognize the transformations of the “Stravinsky” theme); the movement takes shape as a fantastic, animated and richly coloured sequence of changing inventions articulated in an incisive, synthetic and energetic fashion.

TRACK LISTING:

- 1-3: Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 1 [9:06; 7:52; 6:23]

- 4-6: Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 2 [[9:37; 11:45; 6:04]

FINAL THOUGHT:

There is some truly frightening moments in these pieces and must say, I got a little scared listening to this late night alone in my office. There is something about piano and percussion that just makes a person a little jumpy.

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company)

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company)

Congrats on this wonderful piece, I have a script on Bartok with Oscar winners interested. Let’s connect.