Ludwig Van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Ludwig Van Beethoven (1770-1827)

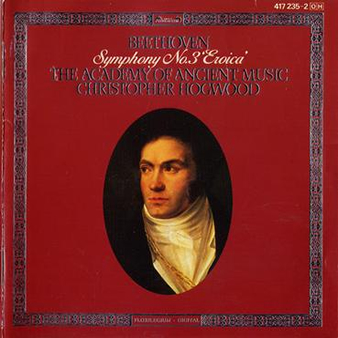

Symphony No. 3 in E-flat Major, Opus 55 – ‘Eroica’

The Academy Of Ancient Music (Christopher Hogwood, Conductor)

Recorded at Walhamstow Assembly Hall, London – August, 1985

ONE-SENTENCE REVIEW:

Even though this symphony, I think, is most effective when performed with the best modern instruments money can buy, this “authentic instrument” recording (thanks, Sir Hogwood) is the standard bearer and generation after generation will forever have this fabulous recording to know exactly how this masterpiece sounded in Beethoven’s day (provided the orchestras in Beethoven’s day didn’t suck).

ORIGINAL LINER NOTES (written by Barry Cooper):

Although Beethoven was born and brought up in Bonn, he moved to Vienna in 1792, at the age of nearly 22. Once there, he quickly became recognized as a virtuoso pianist, and he also become wildly admired for his remarkable ability at improvisation.

His reputation as a composer, however, developed more slowly, and until the end of the century his compositions found favor with only a small number of people. But two works did more than anything to broaden his popularity – the Septet Opus 20 of 1799-1800 and the ballet Die Geschopfe des Prometheus (The Creatures of Prometheus) of 1801.

His reputation as a composer, however, developed more slowly, and until the end of the century his compositions found favor with only a small number of people. But two works did more than anything to broaden his popularity – the Septet Opus 20 of 1799-1800 and the ballet Die Geschopfe des Prometheus (The Creatures of Prometheus) of 1801.

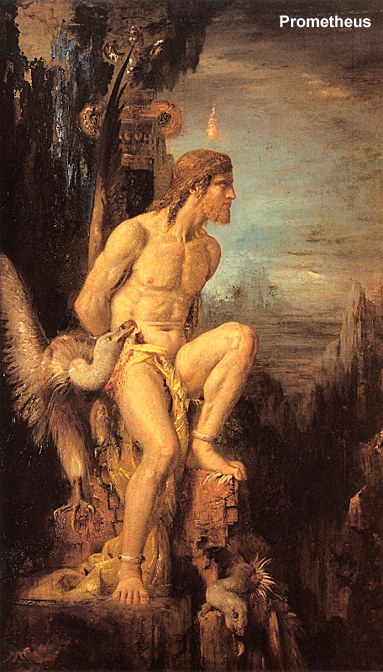

The Prometheus music was to play an important role in the genesis of the Eroica Symphony of 1803, and so an understanding of the ballet and its background is essential for a full appreciate of the Symphony. Ballet in Vienna had reached new heights during the 1790s, with several being produced each year; many were new, with music by such composers as Sussmayr, Weigl and Wranitzky, and most were labelled as belonging to a particular type, such as comic, heroic or tragi-pantomime.

Beethoven’s Prometheus, first performed on 28 March 1801, formed part of this tradition and was described as a ‘heroic allegorical’ ballet (notice the word ‘heroic’).

The work was so successful that it received twenty-three performances in less than two years. The finale appears to have been particularly popular, and Beethoven soon took advantage by arranging the two main finale themes as Contretanze for use at balls (it is sometimes stated that the Contreanze preceded the ballet, but the sketches indicate that ballet undoubtedly came first).

In 1802, he used the principal finale theme again, this time for a set of piano variations Opus 35; he even requested the original publishers to mention on the title page that the them was from Prometheus, though his request was ignored.

As soon as he had finished sketching these variations, he wrote on the next two page of his sketchbook a plan for the first three movements of a symphony in E-flat – a plan that was to evolve into the Eroica Symphony.

The fact that there are no sketches for the finale at this initial stage suggests he had already decided to base this movement on the popular theme from Prometheus,; thus the Eroica became the fourth work to use this theme.

The fact that there are no sketches for the finale at this initial stage suggests he had already decided to base this movement on the popular theme from Prometheus,; thus the Eroica became the fourth work to use this theme.

During the next few months, the planned Symphony lay dormant, but Beethoven returned to it in the middle of 1803. He worked intensively on it throughout the summer, as usual composing the movements in the same order as they appear in the finished version.

By autumn 1803, the Symphony was more or less complete, but he continued touching it up for at least a year or so afterwards and it was not finally published until October 1806.

The Eroica or ‘Heroic’ Symphony was the first of his symphonies to have specific extra-musical associations. But although he doubtless expected the musical reference to his heroic ballet to be instantly recognized by the Viennese public, Prometheus was not the only hero he had in mind.

According to one account, General Abercromby (who had been killed in action in 1801) was the hero was provided the initial idea for the Symphony.

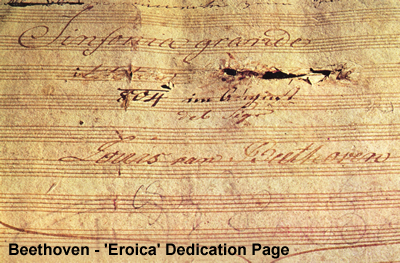

More significantly, Beethoven intended to dedicate the work to Napoleon, whom he regarded as the hero who had overthrown the tyranny of the Anicen Regime. He had even written out a dedicatory title page, when news reached Vienna that Napoleon had proclaimed himself emperor.

More significantly, Beethoven intended to dedicate the work to Napoleon, whom he regarded as the hero who had overthrown the tyranny of the Anicen Regime. He had even written out a dedicatory title page, when news reached Vienna that Napoleon had proclaimed himself emperor.

In a fit of rage, Beethoven is reported to have torn up the page, exclaiming, “Is he too nothing more than an ordinary man? Now he too will trample on all human rights.”

In a manuscript copy of the Symphony which he possessed and which still survives today, Napoleon’s name on the title page is so heavily deleted that there is a hole in the paper.

In the end, the Symphony was dedicated to Prince Lobkowitz, who not only paid Beethoven for the dedication but also enabled him to try out the Symphony several times at the prince’s palace before its first public performance on 7 April 1805.

The work is thus best regarded as a portrayal of the idea of heroism rather than of any individual; the title page of the first edition leaves the matter ambiguous, stating that the Symphony was ‘composed to celebrate the memory of a great man’ (‘compsta per festeggiare il sovvenire di un grand Uomo’) – either the memory of the Napoleon that was (before he became emperor) or of any great man.

The concept of heroism is portrayed in the music in a number of ways, most conspicuous of which is the size of the work. For Beethoven, a hero was apparently a larger-than-life character, and so the Symphony is substantially bigger than any previous one.

The concept of heroism is portrayed in the music in a number of ways, most conspicuous of which is the size of the work. For Beethoven, a hero was apparently a larger-than-life character, and so the Symphony is substantially bigger than any previous one.

In the first movement it is the gigantic development section in the middle of the movement that best portrays the hero, as it builds up to a climax of ferocious discords, followed by a desolate theme in the woodwind and ultimately the triumphant return of the main theme.

The second movement is headed ‘Marcia funebre’ and alternates between minor and major – between mournful melancholy and noble pathos.

In the third movement, a scherzo and trio, the heroic element appears most clearly in the trio, where a theme of uncommon boldness is played on three horns instead of the usual two, giving a much fuller sound. This theme, like many of the main themes in the Symphony, is based on the notes of the tonic chord, a device that contributes much to the heroic quality of the music.

(Some analysts suggest these tonic-chord themes are derived from the two opening chords of the Symphony, but the sketches show that these two chords were very much an afterthought.)

In most earlier symphonies the finale was a relatively light movement, but the Eroica marks the beginning of a trend towards much weightier finales. This is hardly surprising when one remembers that the main themes of the Eroica finale was an important generating factor for the whole Symphony.

Beethoven did not specify any programme in the finale, but it is tempting to see the movement as reflecting the plot of Prometheus. The ballet begins with a storm, and similarly the finale of the Eroica has a stormy opening; next Prometheus encounters two statues he has made, and in the Symphony the stiff, unharmonized bass-line that follows the storm could hardly be more statuesque.

Beethoven did not specify any programme in the finale, but it is tempting to see the movement as reflecting the plot of Prometheus. The ballet begins with a storm, and similarly the finale of the Eroica has a stormy opening; next Prometheus encounters two statues he has made, and in the Symphony the stiff, unharmonized bass-line that follows the storm could hardly be more statuesque.

Prometheus brings the statues to life, and Beethoven likewise breathes life into the empty bass-line by adding various counterpoints, culminating in the addition of the tune borrowed from his ballet.

In the rest of the ballet the now living statues are introduced to various arts, while the remainder of the Symphony Beethoven proceeds to use a great variety of musical arts, including variation, fugue and symphonic development.

The meaning of the ‘allegorical ballet’ is this: Prometheus is a lofty spirit who finds the men of his day in a state of ignorance and civilizes them, making them susceptible to human passions by the power of harmony. Thus it concerns the creative artist, a hero who breathes life into his creations and civilizes those around him. This idea can also be discerned in the gradeur of the Eroica, where the real hero is surely the composer.

It is of course possible to appreciate the Eroica while knowing nothing of its connections with Prometheus and Napoleon. But if we are to make progress towards ‘authentic’ listening, which is the logical counterpart of authentic performances, it is essential to be aware that the original audiences would have understood at once the reference to Prometheus in the Eroica, as well as appreciating that the Symphony was breaking new ground.

It is also important to appreciate the genesis of the work – both its musical and extra-musical origins – so that we can approach it from the same angle as the composer. Such attitudes will certainly enhance our enjoyment of the music, and our receptiveness to the ideas that Beethoven was trying to communicate.

TRACK LISTING:

- 1-4: Symphony No. 3 in E-flat major – Opus 55 – ‘Eroica’

FINAL THOUGHT:

Napoleon had to get all cocky and name himself “Emperor” – doesn’t he realize that Beethoven’s 3rd Symphony could have been dedicated to him? What a dumb ass.

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company)

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company)

Love these posts – heard this at the Hollywood Bowl a few times – great share!

I certainly prefer a modern-instrument performance of this. My own favorite is the Barbirolli/BBC Symphony account (EMI). I know some people find it “sentimental.” but I find it powerful, the affectionate shaping of the lyric themes notwithstanding.

I do like Hogwood’s “Eroica” — I’m not a Hogwood-basher, as much of the musical press seem to be these days — but I think that, among “historical” accounts, it’s outclassed by the Gardiner (DG Archiv).

Steve

A few years ago I prepared a survey of what struck me as the most significant recordings of the Eroica (with heavy emphasis on historical ones), which may be of interest. It’s at http://www.classicalnotes.net/classics3/eroica.html . I’m always interested in others’ views and recommendations.