Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

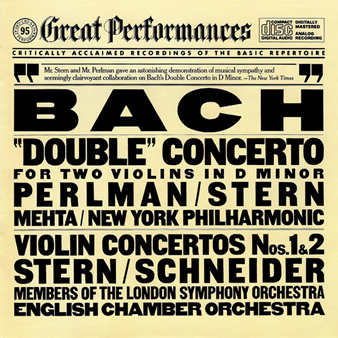

Concerto in D Minor for Two Violins and Orchestra, BWV 1043

Isaac Stern, Itzhak Perlman, New York Philharmonic – Zubin Mehta, Conductor (CBS Great Performances)

Concerto No. 1 in A Minor for Violin and Orchestra, BWV 1041

Members of the London Symphony Orchestra – Isaac Stern, Violinist and Conductor (CBS Great Performances)

Concerto No. 2 in E Major for Violin and Orchestra, BWV 1042

Isaac Stern, English Chamber Orchestra – Alexander Schneider, Conductor (CBS Great Performances)

ONE-SENTENCE REVIEW:

One of the best recordings of J.S. Bach’s music ever made (as long as you ignore all the annoying audience noises in the background).

ORIGINAL LINER NOTES (uncredited):

Most of the concertos of Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1759) – including the six Brandenburgs – were composed in the years 1717 through 1723, the period of his tenure as court organist and director of the orchestra for Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cothen.

Apart from his prowess as organist and conductor, Bach was an accomplished violinist who had, according Albert Schweitzer, “learned from Vivaldi the perfect violin technique, the art of writing ‘singably’… For him there was really only one style that naturally suggested by the phrasing of the stringed instrument – and all other styles are for him only modifications of this basic style.

Apart from his prowess as organist and conductor, Bach was an accomplished violinist who had, according Albert Schweitzer, “learned from Vivaldi the perfect violin technique, the art of writing ‘singably’… For him there was really only one style that naturally suggested by the phrasing of the stringed instrument – and all other styles are for him only modifications of this basic style.

In view of Bach’s predilection for the violin, it is all the more disappointing that only three of his works specifically written for the violin have been left to us.

On the often inaccurate basis of stylistic analysis, scholars have postulated that the majority of Bach’s harpsichord concertos are arrangements of concertos originally written for the violin.

True or not, we have to content ourselves with the two Concertos for Violin and Orchestra and with the Double Violin Concerto.

However, this can scarcely be regarded as a hardship. The Double Violin Concerto is a masterpiece, and the two solo violin concertos are like twins divinely blessed.

The very fact that there are only two has worked in their favor. We do not have to contend with the disappointing knowledge that there are some 350 others, equally good and not strikingly dissimilar, vying for our attention – as in the case of Vivaldi, who, legend says, composed violin concertos even during meals.

And it was Vivaldi who was probably the moving force behind Bach’s violin concertos. Bach had already paid the Venetian master the not inconsiderable compliment of transcribing a number of his published concertos for solo keyboard, and, further, he turned a Vivaldi concerto for four violins into a concerto for four harpsichords.

Curiously, all these transcriptions show Bach rethinking idiomatic violin music in terms of the keyboard. When he came to compose his own violin concertos, the harpsichord – with its self-sufficient contrapuntal possibilities and its quick, unsustained brightness – was entirely forgotten.

Curiously, all these transcriptions show Bach rethinking idiomatic violin music in terms of the keyboard. When he came to compose his own violin concertos, the harpsichord – with its self-sufficient contrapuntal possibilities and its quick, unsustained brightness – was entirely forgotten.

Bach’s violin concertos are not virtuoso showpieces, as Vivaldi’s tend to be, but are conceived completely in violinistic terms.

In form, Bach takes over Vivaldi’s characteristic three-movement, fast-slow-fast pattern. The final movements of both solo concertos, as with Vivaldi, are giguelike dances. The slow movements are again a favorite Vivaldi device – long candilenas over a recurring ground bass.

Only in his first movements does Bach depart somewhat from the practice of Vivaldi and his fellow composers. The general form is the same.: The orchestra is given a distinctive theme, heard at the beginning and end of the movement and also, in abbreviated form, throughout its course; this orchestral ritornello alternates with passages for solo violin.

But while the solo passages in Vivaldi are often merely brilliant displays of virtuosity with small relationship to the ritornello, in Bach the soloist fully shares the thematic material with the orchestra.

The A-Minor Concerto opens with a playful melody, aerated with well-calculated pauses. In this movement, the solo violin is also lighthearted, moving through a rather conventional series of sequential passages with enviable bounce and aplomb.

The Andante is an ostinato piece. The ground bass constantly returns to its thrice-repeated low C, giving it an earthbound quality in contrast to the floating solo violin.

The final gigue has a French grace about its endlessly spun-out triplets. The soloist is given real opportunities here in whirling-dervish speedups of the basic rhythm.

The Violin Concerto in E Major opens with an Allegro in the solid commanding style of the Brandenburgs, with three proclamatory chords that echo persistently throughout the movement. The soloist plays in real dialogue with the orchestra; there is no rigid separation of tutti and solo.

The Violin Concerto in E Major opens with an Allegro in the solid commanding style of the Brandenburgs, with three proclamatory chords that echo persistently throughout the movement. The soloist plays in real dialogue with the orchestra; there is no rigid separation of tutti and solo.

The Adagio begins and ends with the low strings stating a long, rather melancholy, ostinato bass. Over this, the violin sings a tender song in phrases that seem endless and are virtually devoid of cadential points.

The Allegro assai is one of Bach’s business-like finales – staid, self-assured, rather “fat” in instrumental texture. The movement, with its alternation of ritornello and solo, comes closer to the Vivaldi ideal of Baroque concerto writing than does the first movement.

The Concerto in D Minor for Two Violins and Orchestra was also written during Bach’s Cothen period when the nature of his appointment forced him to concentrate on instrumental music.

It holds a unique position among the many compositions that he wrote for the Court band of some eighteen pieces, for the possibilities of contrasting two solo instruments removed this work substantially from the customary concerto type.

This is particularly true of the slow movement, in which the discourse of the two violins reduces the orchestra to a very subordinate position.

Back too full advantage of the aptitude of the violin for melodic beauty. He set the two instruments against each other in a veritable dialogue, with the orchestra providing harmonic and rhythmic background.

As in many of Bach’s concertos, the slow movement is the point of gravity of the entire composition, flanked by two fast and more or less conventional sections.

TRACK LISTING:

- 1-3: Concerto in D MInor for Two Violins and Orchestra, BWV 1043

- 4-6: Concerto No. 1 in A Minor for Violin and Orchestra, BWV 1041

- 7-9: Concerto No. 2 in E Major for Violin and Orchestra, BWV 1042

(Sorry, I found no video of the Isaac Stern / Itzhak Perlman recording. Those two hacks above will have to do.)

FINAL THOUGHT:

The “Double Concerto” is featured in one of my favorite movies – Woody Allen’s “Hannah & Her Sisters.” The opening strains of the piece take me immediately to the scene where Sam Waterston is giving Dianne Wiest and Carrie Fisher an architectural tour of New York. This CD is a great workhorse classic and has many of Bach’s “hits” that most people will recognize immediately. It is a well-earned “88” on my piano scale!

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company)

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company)

Hello, this is for your pleasure and participation,

Happy Valentines day, Here is a new song and short movie from Sam Sallon. This is a beautiful site with a 3 minute mini movie. Also enjoy for trailers from around the world. We are asking for your opinion on the idea of using your smartphone to pick the winners as interactive audience participation by mobile in theaters. The grand prize is $3k plus much more.

The International Movie Trailer Festival ran this contest for mobile movie makers. The challenge: Use a smartphone or tablet to shoot a two minute trailer of a movie in the dream stage. We received entrants from ten countries and

many from the USA. We are reaching out to festivals and indie film venues to play a six minute short of the winners prior to scheduled shows. You can view them here at our site International Movie Trailer Festival I am asking that you review all of this, share it with your friends and give us your thoughts. Looking forward to your feedback.

Cheers, have a great day

Ronald Sallon