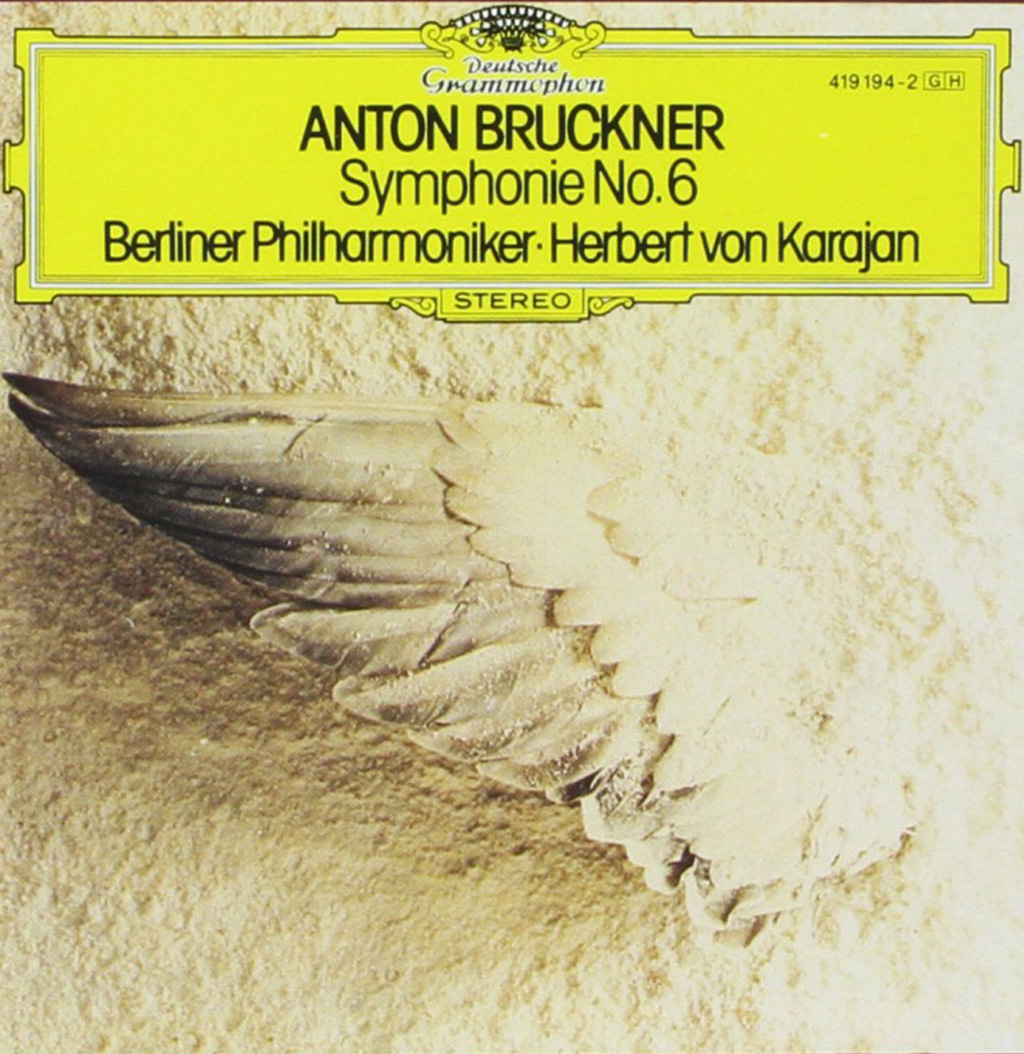

Anton Bruckner (1824 – 1896)

———————

Herbert Von Karajan, Conductor

Berliner Philharmonic

Recorded 1980, Berliner Philharmonie – Berlin, West Germany

———————

ONE-SENTENCE REVIEW:

One word – ROUSING!

———————

ORIGINAL LINER NOTES by Richard Osborne

“Listen to the music with reverence; for the composer meant what he said, and he was speaking of sacred things,” wrote Sir Donald Tovey of the Sixth Symphony’s slow movement.

It is well said, for this is wise and compassionate music, Sachs-like in its broodings. Tovey’s advocacy of the symphony in the early years of the century was remarkable then and would be remarkable now, for the Sixth – personal, economical, thrillingly shaped and scored – has never been much noticed by the wider musical public.

During Bruckner’s lifetime only the Adagio and Scherzo of the Symphony were known. Wilhelm Jahn, director of the Vienna Hofoper, had conducted these two movements, to considerable acclaim, at a Philharmonic concert in Vienna in February 1883, seventeen months after the work’s completion.

But it was Gustav Mahler who brought the full score to public notice (albeit with cuts in some of the third subject groups and some revised orchestration) at a concert in Vienna in February 1899.

Mahler had long wanted to present a Bruckner symphony to the Philharmonic audience, and his choice was as enterprising as it was inspired. One wonders what Mahler made of the work in performance.

He was himself to write slow movements of omparable beauty, but his dance movements, with their persistent nostalgia, their recurrent irony, and their sophisticated orchestral method rarely, if ever, attempt to re-appropriate and re-fashion the classical scherzo as fascinatingly as Bruckner does.

Bruckner’s Trio, with its woodland horns and haunting sense of an Urwald far distant in time from our own, is a minor masterpiece in itself.

Like the trudging start to the Scherzo (which may or may not have given Mahler a germinal idea for his own Sixth Symphony), Bruckner’s music is rooted in certainties which Mahler all too rarely glimpsed.

Bruckner’s two outer movements are incluctably splendid; but they, too, follow a ground-plan, and an orchestral procedure, radically different from anything we encounter in Mahler.

Spacioius in design, swift in process, without a spare ounce of flesh on the orchestral texturing, the finale searches out the tonic A major – the key briefly burked out by trumpets and horns in bar 23 of the movement across a quietened, minor-key, nocturnal landscape.

During the course of the movement there are many arrivals on precipitate tonal steeps, as well as blander, blanket moments, abortive fermatas marking journey’s end.

“In Bruckner,” Robert Simpson has brilliantly observed, “the unexpected is inevitable, and the inevitable totally unexpected.” This is certainly true of the Sixth’s finale. Its mood is by turns furtive, heroic, feverish, serene and assertive. Never, though, is it despairing. It is a movment marked by a heroic refusal to contemplate victory until all the possibilities of defeat have been squarely faced. Onlly out of doubt is faith born.

The first movement is almost unequivocally splendid! Is there a recapitulation in the history of the symphony between Beethoven and Silelius more unexpected or more thrilling that that at the heart of this particular movment?

The use of the drum is Beethovenian both as an harmonic pivot and as a source of awesome splendor in the orchestral texture; but though the effects are Beethovenian in origin they are entirely Brucknerian in their application.

Earlier, the movement begins with the note of C sharp pulsing like rapid morse high on the violins – though the crucial ideas are held, with typical Brucknerian reticence, low in the cellos and basses.

Here, within a characteristically plain tonic and dominant ambit, an array of highly charged Neopolitan harmoniers give the music its special charisma, just as broad rhythmic formulations are soon to give focus to the exquisite lyrical episodes, the music made magical by the arcane loveliness of the kaleidoscopically changing inner rhythmic fragments.

By the code, as Tovey eloquently observes, the thematic inversions are ‘passing from key to key beneath a tumultuous surface, sparkling like the Homeric seas.’

TRACK LISTING:

Anton Bruckner (1824 – 1896) – Symphony No. 6 in A Major

- Majestoso [15:16]

- Adagio: Sehr feierlich [18:58]

- Scherzo: Nicht schnell – Trio, Langsam [7:52]

- Finale: Bewegt, doch nicht zu schnell [15:13]

FINAL THOUGHT:

If you’ve decided to listen to some Brucknertoday – start with this one. Your heart rate will rise. Most doctors say Bruckner’s 6th equals one hour of cardio.

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company

Admiring the time and effort you put into your blog and detailed information you offer!.. direct to film transfers

Admiring the time and effort you put into your blog and detailed information you offer!.. tesla refrigerator

Admiring the time and effort you put into your blog and detailed information you offer!.. DC Wallbox Charger