Anton Bruckner (1824 – 1896)

———————

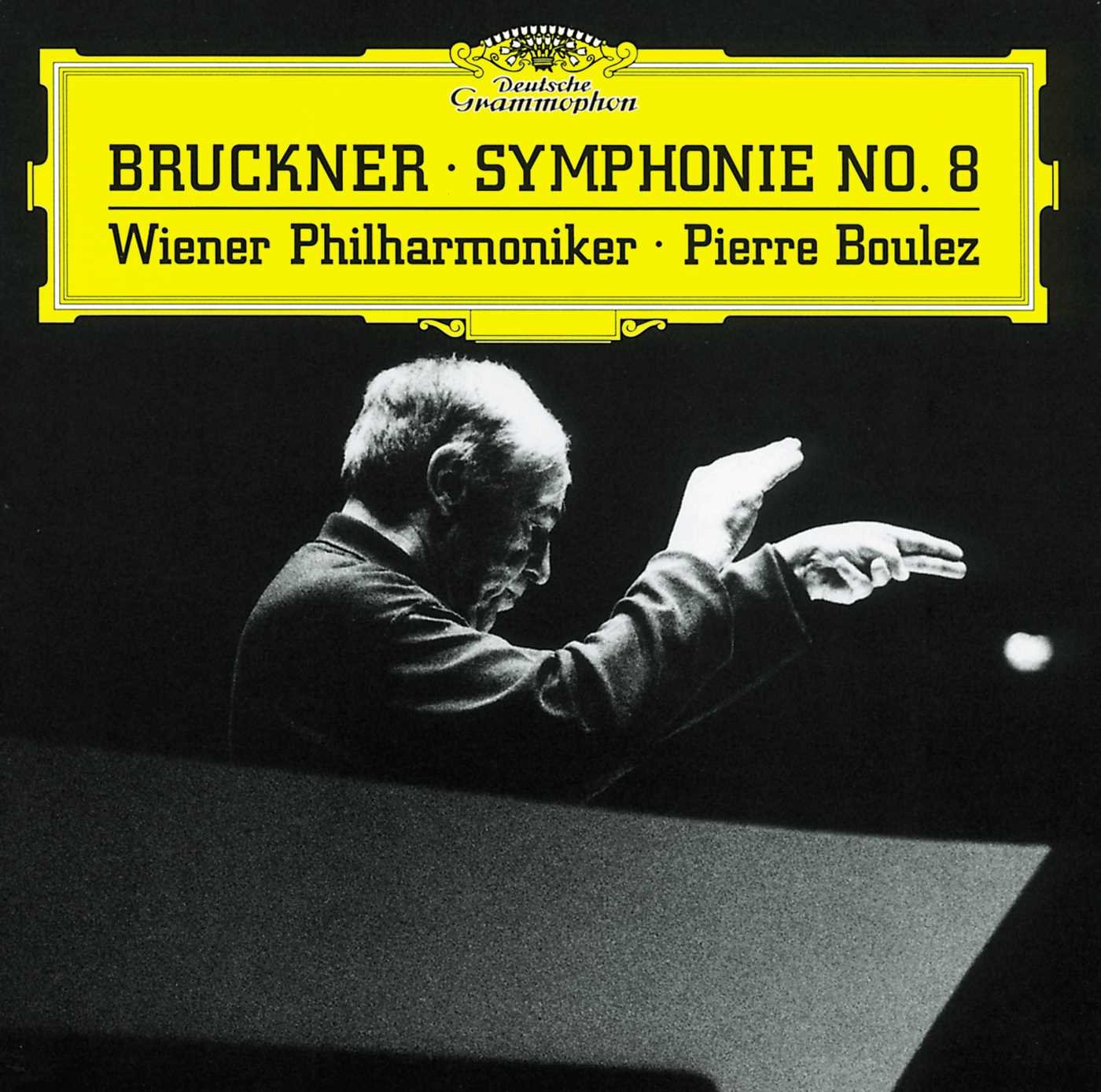

Pierre Boulez, Conductor

Vienna Philharmonic

Recorded live at St. Florian, near Linz at the International Bruckner Festival 1996

———————

ONE-SENTENCE REVIEW:

Sorry, Anton, this bloated bore of a Symphony is about as boring as it can get – and it’s not the band (or Pierre Boulez’s fault).

ORIGINAL LINER NOTES by Ewald Mark (translated by Stewart Spencer)

THE PROJECT:

In September 1992, after a magnificent concert in London by the Vienna Philharmonic under Pierre Boulez, the conductor and the orchestra’s then managing director, Walter Blovsky, found themselves sitting next o each other at a reception and doing what conductors and orchestra managers like doing most of all; drawing up plans for the future.

When in the course of their conversation, Blovsky floated the idea of a performance of Bruckner’s Eighth Symphony in the Abbey Church at St. Florian in September 1996. Boulez asked for time to think it over. After all, that would mean departing from the preferred practice of performing the work in the concert hall before recording it in the studio.

But the diaries of both the conductor and the orchestra allowed for only a live recording. It was not long, however, before Boulez gave the project his blessing after rehearsing at the Musikverein in Vienna, they would travel to Linz and stay there, with further rehearsals and the concerts themselves at St. Florian on 21 and 22 September. These would be filmed by Euroart and ORF and recorded by Deutsche Grammophon.

APPROACHES TO BRUCKNER:

In 1970, Boulez wrote an article for the Bayreuth Festival programme, “Approaches To Parsifal,” an article which, twenty-six years later in Vienna, encouraged me to ask the composer and conductor about his approach to Bruckner.

When Boulez receied his musical training between 1943 and 1946, Bruckner was virtually unknown in France – merely a name in books on the history of music, nothing more. According to Boulez, the general attitude to Bruckner was more or less that “he’s good enough for Central Europe but of no interest to us.”

But, as Boulez goes on, “there are two reasons why I can’t accept this point of view. First, the French have always been fanatical about Wagner, his chromatic language had a profound influence on them.

Secondly, they have always been particularly receptive to this kind of harmonic language – at least from Debussy onwards. So I simply don’t understand why the French weren’t immediately conscious of the wonderful harmonic language, this lacyrinthine harmonic language.”

Charles Munch hailed from Alsace but taught at the Leipzig Conservatory while playing in the Gewandhaus Orchestra under Wilhelm Furtwangler and Bruno Walter. Pierre Montreux worked as guest conductor with the Concertgebouw Orchestra in Amsterdam alongside Willem Mengelberg. And Andrei Ouytens was the first Frenchman to conduct at Bayreuth.

All three men regularly conducted Beethoven, Brahms and Wagner in the concert hall and recording studio, while ignoring Bruckner’s works. It was left to Daniel Barenboim during his years with the Orcestre de Paris to introduce Brucker’s symphonies to French audiences. But for the musicians, too, these scores were terra incognita, and the orchestra even had to acquire a set of Wagner tubas in order to be able to produce the right sound.

The Eight Symphony Under Klemperer That Was The Fifth.

A key experience for the elderly Igor Stravinsky was a gramophone recording of Bruckner’s Ninth Symphony with the Columbia Symphony Orchestra under Bruno Walter. Did Boulez have a similarly seminal experience with Bruckner?

The conductor recalls that during the 1960s he was often in London and regularly took the opportunity to hear Otto Klemperer conduct. He heard Beethoven, Mahler and, for the first time, Bruckner. When, in the course of the discussion mentioned at the outset, the question arose as to which of Bruckner’s symphonies he might like to conduct at a concert with the Vienna Philharmonic, he spontaneously chose the Eighth, because this, he said, was the work that had left such a deep impression on him when he had heard it under Klemperer with the Philharmonia Orchestra.

Many years later Klemperer’s daughter Lotta explained that it had in fact been the Fifth that Boulez had heard on that occasion. To this day, Boulez remains uncertain as to whom he owes his introduction to the Eighth. But at least he now knows that ‘memory always counterfeits the very thing one wants to feel.’

A Plea In Favor Of the Haas Edition

Any performance of a Bruckner symphony naturally begs the question as to which edition to prefer. It is a question that Pierre Boulez has had to confront in turn. He decided in favor of the Haas edition, as it seemed to him that the cuts in the Nowak version are unnecessary. ‘They sometimes destroy the symmetry, logic and structure.’

Equally clear-cut was his decision to choose the ‘original version’ in preference to that of 1887: ‘In the 1887 version the first and fourth movements end in the same way, whereas in the ‘original version’ the epilogue of the opening movement dies away ppp.’

Pierre Boulez is also familiar with some of Bruckner’s letters and with the anecdotes that have grown up around the composer. There is a passage, for example, in which Bruckner expresses his ‘deep emotion and gratitude to the highly esteemed Philharmonic Society‘ on the occasion of the first performance of the Eighth Symphony in 1892.

As an example of opportunism, this takes some beating and strikes more or less the same note as Wagner’s letters to King Ludwig II. ‘For me,’ says Boulez, ‘the boundary between a composer’s life and works is uncrossable. Or, to put it another way, the score is always the main thing for me.’

After studying the score in detail, therefore, Boulez can image that the double-dotted rhythms may be played more tautly by the orchestra, very much as ears attuned to Stravinsky and Bartok might expect them to be played. But then, with typically French generosity, he qualifies his remark: ‘From the very outset, I accepted that I would undoubtedly get more from the orchestra than they would get from me.’

Acoustic Problems

Both as a member of the audience and as a conductor, Pierre Boulez has had ample experience of the vagaries of church acoustics. He still clearly remembers a performance of Berlioz’s Symphonie funebre et triomphale at St. Paul’s Cathedral in London and the nerve-racking struggle of the solo trombones with the building’s infamous echo.

During the summer of 1975 he conducted Mahler’s Ninth Symphony with the New York Philharmonic in Chartres Cathedral and recalls: ‘The performance of the fourth movement was ideal, but in the second and third movements in particular the audience heard absolutely nothing. Yet is was impossible to play it any slower, otherwise it would have lost all character. Because of this, one is willing to make compromises, but a compromise must not be taken too far.’

When the Vienna Philharmonic performed Bruckner’s Eighth Symphony under Pierre Boulez in the Abbey Church of St. Florian in September 1996 – only weeks before the centanary of Bruckner’s death – it was unnecessary to make any such compromises. This, after all, is the church in whose crypt the composer lies buried in a simple sarcophagus placed beneath the great organ that bears his name.

Or to put it another way; a great 20th Century composer has been paid homage to one of the great composers of the 19th Century.

Ewald Markl (translation: Stewart Spencer)

TRACK LISTING:

Anton Bruckner (1824 – 1896) – Symphony No. 8 in C Minor

- Allegro Moderato [15:08]

- Scherzo: Allegro Moderato – Trio, Langsam, Scherzo Da Capo [ 13:39]

- Adagio: Feierlich Langsam, Doch Nicht Schleppend [24:52]

- Finale: Feierlich, Nicht Schnell [22:19]

FINAL THOUGHT:

Come at me, Bruckner-ites – but I can’t get behind this one. The work, not the performance. It’s just a bore. Go back to Symphonies 3-6 for the good stuff.

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company

Pretty good post. I just stumbled upon your blog and wanted to say that I have really enjoyed reading your blog posts. Any way I’ll be subscribing to your feed and I hope you post again soon. Big thanks for the useful info. بت یک

Pretty good post. I just stumbled upon your blog and wanted to say that I have really enjoyed reading your blog posts. Any way I’ll be subscribing to your feed and I hope you post again soon. Big thanks for the useful info. iblbet

You make so many great points here that I read your article a couple of times. Your views are in accordance with my own for the most part. This is great content for your readers. AK Lasbela

This is very educational content and written well for a change. It’s nice to see that some people still understand how to write a quality post.! chakibet

This is truly a great read for me. I have bookmarked it and I am looking forward to reading new articles. Keep up the good work!. lcctoto

Thanks for the blog loaded with so many information. Stopping by your blog helped me to get what I was looking for. lcctoto