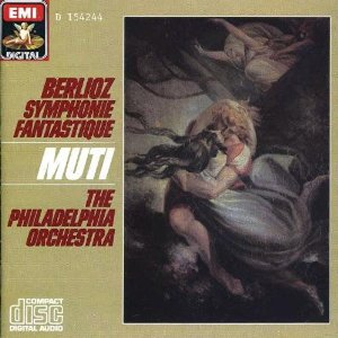

The Philadelphia Orchestra, Riccardo Muti – Conductor

Recorded in 1985 (EMI Records)

ONE-SENTENCE REVIEW:

Symphonie Fantastique – it’s not just the creepy music from the insipid Julia Roberts movie “Sleeping With The Enemy.”

ORIGINAL LINER NOTES (by James Harding, 1984):

Fifty years ago Berlioz was out of fashion compared with today, and there were far fewer chances of hearing his music.

Writing in the mid-thirties, the English critic James Agate observed: “Two reasons why Berlioz is unpopular in this country – nine-tenths of musical critics have not the ears to hear him, and the public, not knowing whether to sound the “z” or not, is shy of mentioning him. It will be eighty years before the work of this composer ceases to be what the American book reviewer calls a “flop d’estime.”

Add to this the fact that there is, with the possible exception of Le Carnaval Romain, hardly a whistleable tune in the whole of Berlioz, and one can understand the neglect of his music. He has since, however, achieved his right place, and more quickly than Agate’s pessimism warranted.

Yet, as always with this most paradoxical of composers, even his warmest admirers can find something to criticize.

Yet, as always with this most paradoxical of composers, even his warmest admirers can find something to criticize.

Why didn’t he end the Symphonie Fantastique with the Marche au supplice?, Agate inquired. “Sheer composer’s vanity, of course, and some nonsense about finishing the story. Also because, like Wagner, he had no sense of the point at which, in the hearer, saturation is reached. The Marche is one of the most final things in music, in the sense of bringing a work to an end; there is no more going beyond it than you can go beyond the buffers at Euston station.”

Many other people have thought the same, among them the musician Hippolyte Chelard, a close friend of Berlioz, who believed the Marche au supplice, which the composer salvaged from his unfinished opera Les Francs-Juges, to be the finest thing in the whole work.

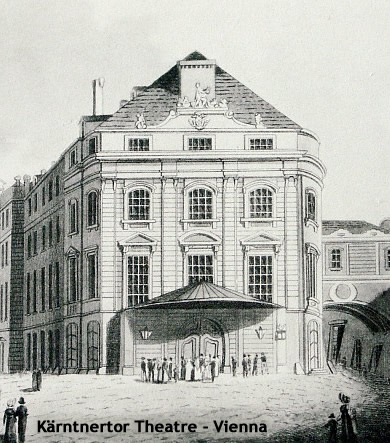

What, though, would have been the reaction of an average middle-aged Parisian music lover in 1830 when the Symphonie Fantastique was first heard?

Remember, he would have been brought up on the classical symphonies of Mozart and Haydn. He would have thought Hummel a greater composer than Beethoven who had died three years earlier.

In any case, at that time, with no radio or gramophone records, music traveled much less fast, and a Beethoven symphony was still a novelty in Paris – or, rather, in the eyes of most, an aberration perpetrated by a madman.

How would our average music lover have responded to the ‘programme’ which Berlioz insisted on distributing among the audience?

How would our average music lover have responded to the ‘programme’ which Berlioz insisted on distributing among the audience?

Imagine his puzzlement at being asked to believe that the music, an ‘episode in the life of an artist,’ represented the feelings of a young man who, hopelessly in love, takes opium and plunges into a sleep haunted by strange hallucinations.

The first movement, Reveries et passions, shows him dreaming of his beloved, an idee fixe which obsesses him.

Then, at a ball, he perceives her in a swirling waltz.

During the third movement, Scene au champs, he finds momentary peace in the countryside but is troubled anew by his unrequited love.

He dreams he has murdered her, and the Marche au supplice takes him to the scaffold.

The Songe d’une nuit de Sabbat features the motif which stands for his faithless love and distorts it into a Witches’ Sabbath where evil spirits gather to bury the artist’s headless corpse and intone a hideous parody of the Dies Irae.

The views of our average music lover were doubtless echoed by composers of the time.

The views of our average music lover were doubtless echoed by composers of the time.

After studying the score Rossini is said to have murmured: “What a good thing it isn’t music.”

When the twenty-two-year old Mendelssohn heard it in 1831 he pronounced it “utterly loathsome.” He added that there was “nowhere a spark, no warmth, utter foolishness, continued passion represented through every possible exaggerated orchestral means….” The Symphonie Fantastique was “indifferent drivel” and “unspeakably dreadful… I have not been able to work for two days.”

Unlike the writer Stendhal, who in 1835 remarked that he had taken a ticket in a lottery which would bring him fame in 1935, Berlioz did not have quite so long a wait.

In his lifetime he was hailed by the poet Theophile Gautier as one of that great Trinity of Romanticism which also included Victor Hugo and the artist Delacroix.

Over the year the technical clumsiness of his scoring which so offended generations of purists has come to be seen as the price paid for a genius whose dazzling originality and fertile inventiveness are at last recognized as unique in music.

TRACK LISTING:

- 1: Reveries – Passions [15:35]

- 2: Un bal [6:09]

- 3: Scene aux champs [16:02]

- 4: Marche au supplice [6:44]

- 5: Songe d’une nuit de Sabbat [9:43]

https://youtu.be/rQXtC6B3CKQ

FINAL THOUGHT:

While certainly not one of the greatest symphonies of all time (in my opinion), it certainly didn’t deserve the treatment or the reviews of Mendelssohn or Rossini. Do those talentless jerks seriously think they can do any better?

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company)

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company)