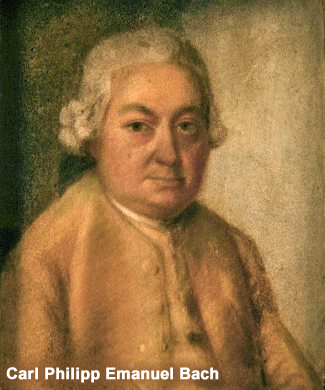

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

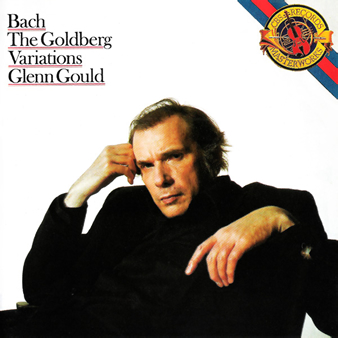

Concerto No. 1 for Piano & Orchestra in D Minor, BWV 1052

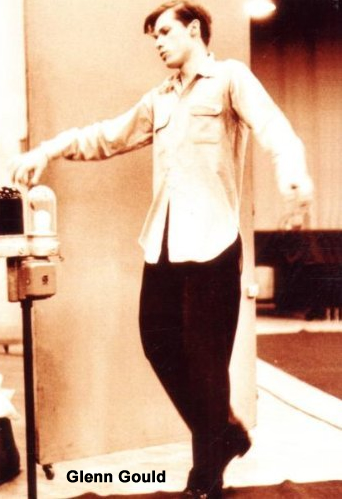

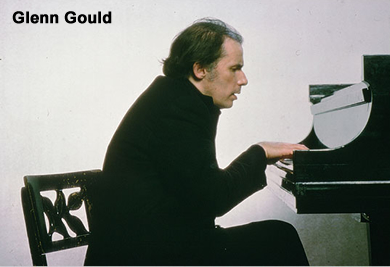

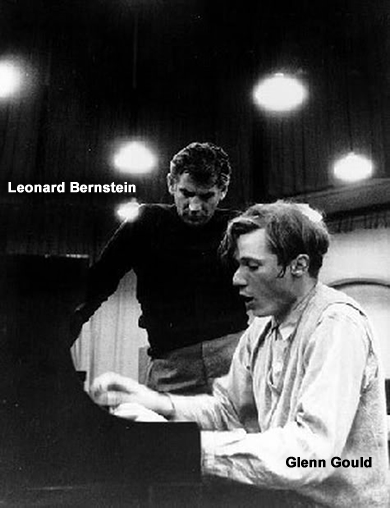

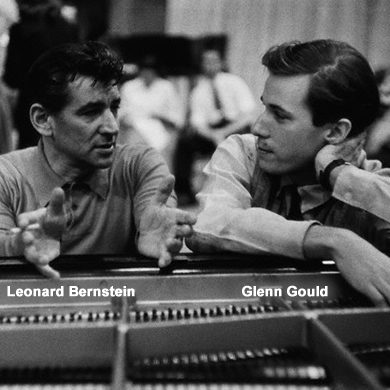

Glenn Gould, Piano – Columbia Symphony Orchestra (Leonard Bernstein – Conductor). Recorded at 30th Street Studio, New York, 1957 (CBS Records)

Concerto No. 4 for Piano & Orchestra in A Major, BWV 1055

Glenn Gould, Piano – Columbia Symphony Orchestra (Vladimir Golschmann, Conductor). Recorded at 30th Street Studio, New York, 1959 (CBS Records)

Concerto No. 5 for Piano & Orchestra in F Minor, BWV 1056

Glenn Gould, Piano – Columbia Symphony Orchestra (Vladimir Golschmann, Conductor). Recorded at 30th Street Studio, New York, 1958 (CBS Records)

ONE-SENTENCE REVIEW:

Who am I to disagree with Robert Schumann (see below)?

ORIGINAL LINER NOTES (uncredited):

In 1837, a noted keyboard virtuoso gave a performance of J.S. Bach’s Clavier Concerto No. 1 in D Minor, after which an influential music journalist had the following remarks to make:

“I should like to speak of many thoughts that were awakened in my mind by this noble work… Will it be believed that on the music shelves of the Berlin Singakademie, to which old Zelter bequeathed his library, at least seven such concertos, and a countless number of other Bach compositions, in manuscript, are carefully stowed away? Few persons are aware of it; but they lie there notwithstanding. Is it not time, would it not be useful for the German nation, to publish a perfect edition of the complete works of Bach? The idea should be considered, and the words of a practical expert, who speaks of this undertaking on page 76 of the current volume of the Neue Zeitschrift fur Musik, would serve as a motto. He says: ‘The publication of the works of Sebastian Bach is an enterprise I hope soon to see in execution – one that delights my heart, which beats wholly for the great and lofty art of this father of harmony.'”

“I should like to speak of many thoughts that were awakened in my mind by this noble work… Will it be believed that on the music shelves of the Berlin Singakademie, to which old Zelter bequeathed his library, at least seven such concertos, and a countless number of other Bach compositions, in manuscript, are carefully stowed away? Few persons are aware of it; but they lie there notwithstanding. Is it not time, would it not be useful for the German nation, to publish a perfect edition of the complete works of Bach? The idea should be considered, and the words of a practical expert, who speaks of this undertaking on page 76 of the current volume of the Neue Zeitschrift fur Musik, would serve as a motto. He says: ‘The publication of the works of Sebastian Bach is an enterprise I hope soon to see in execution – one that delights my heart, which beats wholly for the great and lofty art of this father of harmony.'”

The virtuoso who performed the Concerto was Felix Mendelssohn. The music journalist was Robert Schumann. The “expert” cited was Ludwig Van Beethoven. The quotation was from a letter Beethoven wrote to the music publisher Hofmeister in 1801. So much for establishing the validity and stature of Bach’s clavier concertos as great works of musical art.

To a certain extent, such a validation is necessary for the present-day listener, since Bach’s keyboard concertos differ in many ways from the archetype of the concerto as it was established in the nineteenth century.

To begin with, there is nothing of the heroic drama engendered by the opposition of forces as in the Romantic concerto. In the Brahms Second Piano Concerto – to take a random example – the soloist and the orchestra are pitted against each other as adversaries in a titanic struggle.

To begin with, there is nothing of the heroic drama engendered by the opposition of forces as in the Romantic concerto. In the Brahms Second Piano Concerto – to take a random example – the soloist and the orchestra are pitted against each other as adversaries in a titanic struggle.

Not so with Bach. Nor is there, in his keyboard concertos, even much of the opposition and contrast of the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century concerto grosso, or for that matter, of the Vivaldi violin concerto. Rather, since the clavier plays even in the orchestral tutti, the works are completely clavier-dominated.

In the worlds of Philipp Spitta, the German music scholar and author of a biography of Bach, “These works are, we may say, clavier compositions, cast in concerto form, that have gained in tone, parts, and color through the cooperation of string instruments.”

In the genesis of Bach’s clavier concertos, we find additional differences. The nineteenth century established originality as a primary standard for judging the artistic merit of a work. But such a standard was, in many ways, foreign to earlier times.

One may see, in early painting and graphics, near-identical layouts of subject material, differing only in the stylistic elements that the artist brought to the execution of the idea (and sometimes not even that).

And in the music of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and earlier, thematic ideas and harmonic progressions are to be found floating freely from one composer to another; sometimes whole movements or even whole compositions were adapted and reworked; and, certainly, and most commonly, composers refashioned their own materials to fit new forms or fulfill new functions.

The majority of Bach’s clavier concertos fall into this latter category as rewrites of previously existing concertos, mostly for violin. Herein lies a principal reason for the clavier domination of the works, for the part previously assigned to the solo violin is now given to the keyboard player’s right hand, and the left hand, as if it were another instrument, plays a bass part.

The majority of Bach’s clavier concertos fall into this latter category as rewrites of previously existing concertos, mostly for violin. Herein lies a principal reason for the clavier domination of the works, for the part previously assigned to the solo violin is now given to the keyboard player’s right hand, and the left hand, as if it were another instrument, plays a bass part.

In fact, Bach’s usage of the musical material contained in these works did not stop with the concertos themselves. Movements from them can be found re-worked and re-orchestrated and fulfilling a completely new function in the church cantatas he wrote for later occasions.

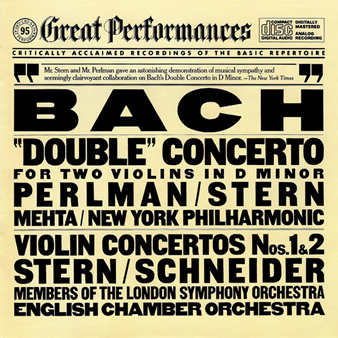

No antecedent is known for Concerto No. 4 in A Major,although despite being a bit more keyboard-like in figurational detail than most of the other concertos, it is still presumed to have been based on a violin (perhaps oboe?) original.

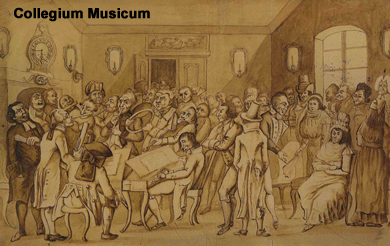

Two final points remain to be made about the concertos, the first having to do with the occasions for which they were composed. Bach went to Leipzig to become Cantor of the Thomasschule – a fairly prestigious position and one that involved an enormous amount of labor, all of it devoted to sacred music. Since Bach’s musical interests extended beyond the boundaries of the sacred, it is not altogether surprising that, in 1729, he added to his responsibilities the job of conductor of the Collegium Musicum, a purely secular society.

The Collegium Musicum met one a week, in Zimmermann’s coffee house, or, in summer months, in his garden. For those meetings, Bach supplied secular cantatas and instrumental music, including the seven known complete clavier concertos (there exists a fragment of an eighth).

The Collegium Musicum met one a week, in Zimmermann’s coffee house, or, in summer months, in his garden. For those meetings, Bach supplied secular cantatas and instrumental music, including the seven known complete clavier concertos (there exists a fragment of an eighth).

Personnel for an orchestra was invariably present at these meetings, as was something of an audience. And Herr Zimmermann, perhaps impressed by Bach’s reputation as a virtuoso organist and harpsichordist, purchased for the meetings an exceedingly fine, large, double-manual harpsichord. It was a happy combination of factors, for the concertos played at these meetings were probably the first clavier concertos ever written.

The presence, too, of an audience was significant in the history of music, for it signaled, in its small way, the movement away from the church and the court and toward the public concert as a center of music.

TRACK LISTING:

- 1-3: Concerto No. 1 for Piano & Orchestra in D Minor, BWV 1052

- 4-6: Concerto No. 4 for Piano & Orchestra in A Major, BWV 1055

- 7-9: Concerto No. 5 for Piano & Orchestra in F Minor, BWV 1056

FINAL THOUGHT:

I would have loved to be a fly on the wall during the Leonard Bernstein/Glenn Gould recording sessions. What did they talk about during lunch? Imagine Glenn Gould’s reaction to Lenny’s smoking, drinking and cursing!

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company)

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company)