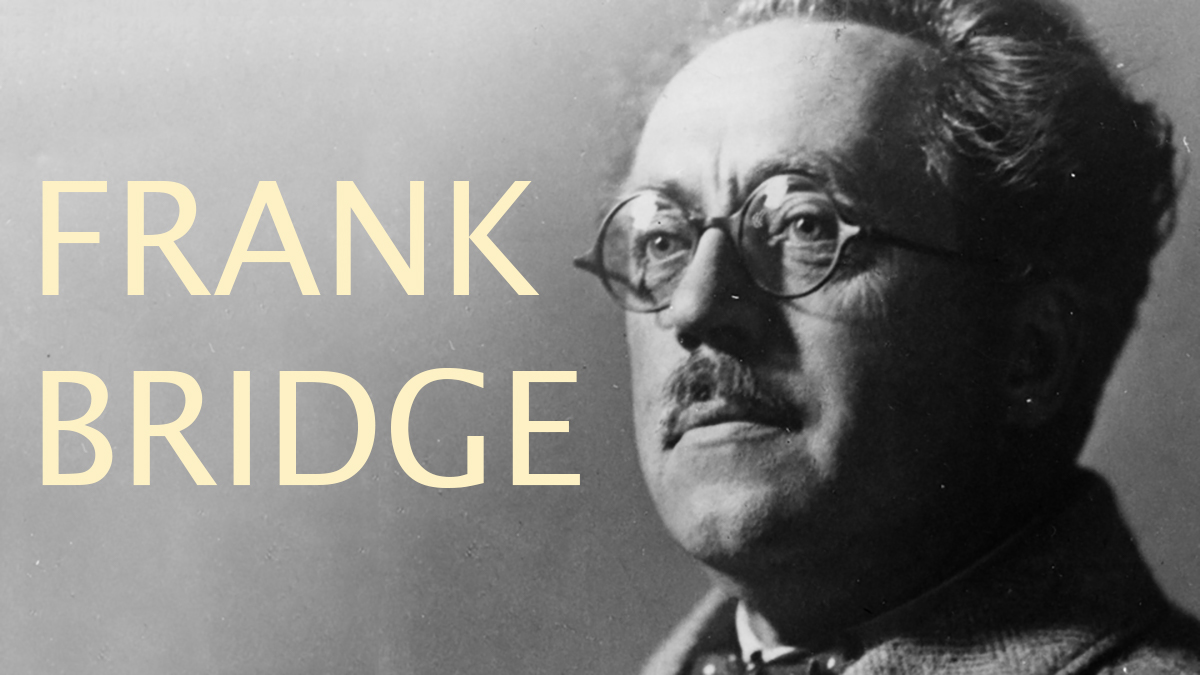

Frank Bridge (1879-1941)

String Quartet No. 2 in G Minor

Performed by: Brindisi String Quartet (Jacqueline Shave – Violin; Patrick Kiernan – Violin; Katie Wilkinson – Viola; Jonathan Tunnell – Cello).

Recorded at: St. Silas Church, Kentish Town, London – June 1991.

Recordings made with financial assistance from the Frank Bridge Trust.

ONE-SENTENCE REVIEW:

While my Emily’s Music Dump music collection only has Volume 2 of the Complete Frank Bridge String Quartets (No.’s 2 and 4), I get a pretty good idea of all four based on this CD – and I like them – they’re lush with an undercurrent of sorrow (regardless of the muffled sound quality and poor production values).

ORIGINAL LINER NOTES – Anthony Payne – 1991.

Frank Bridge’s String Quartets

Bridge left what is arguably the most intensely personal and richly varied legacy of chamber music by any 20th-century British composer. His dialectical methods and civilized artistry were perfectly suited to the medium, and every step in his extraordinary stylistic development can be charted through his contributions to the medium.

The peak of this output is represented by the four string quartets, which encapsulate the four main stylistic periods into which his work can be seen to fall. They present a complete portrait of the composer in all his technical mastery and expressive daring.

The First Quartet, named the Bologna following its success there in a competition in 1906, is the composer’s first large-scale work of real identity, and it brings to a peak his early preoccupation with the string quartet medium, capitalizing on the experience gained from writing the Phantasy String Quartet (1905) and the two sets of salon pieces, Novelletten (1904) and Idylls (1906).

It is a work that tells us much about the newly emergent composer, an exceptionally adroit craftsman for a 25-year-old at this period in English music, yet also cautious in what he expects of his players and listeners. There is a revealing lack of those knotty incidents in melody and texture which would suggest the young composer coming to grips with an individual vision.

We can perhaps conclude that Bridge was the type of artist whose creative personality was initially founded on a natural gift for composition and a strong feeling for good taste, rather than on a burning sense of his own uniqueness as a human being. That was only to develop later.

Bridge’s skill was in advance of all his contemporaries at this time, but his first consideration was accessibility and practicality – admirable tenets. If harnessed to pressure of vision, but dangerous when given over-riding importance, compelling the composer to use familiar tags, explore well-charted emotional territories, and smooth all corners and edges.

In this way growth can be hindered, and it is not surprising that some saw the composer as ‘too professional’ in his methods. Luckily for his art, Bridge later developed a strong curiosity about styles and techniques outside his immediate world, and allowed his growing store of emotional experience to connect with his compositional mastery; but this is not prefigured in his early music.

Despite these considerations, however, the First Quartet is still an admirable achievement. The slow movement, a ‘song without words,’ and the gracious scherzo and trio are redolent of Bridge’s salon style, but the opening sonata structure announces the composer’s wider aims. It was a mistake, perhaps, to treat the easy-going second subject at length in the development prior to extending it even further during the recapitulation, but the evolution of new material by combining first- and second-subject motives marks a real structural achievement, and the spaciousness of the movement as a whole shows Bridge’s early sense of musical architecture.

This, rather than the invention of immediately memorable individual incidents, was always to be the main embodiment of his thought. Both the intervallic content of the opening theme, for example, and its rhythmic outline prove to be motivically fruitful, and already we find first-movement material clinching paragraphs in the third and fourth movements – a characteristic unifying process.

Bridge’s first mature chamber music masterpiece, the Second String Quarter (1915), still has ties with the past, perhaps because ideas for the work had germinated over a long period, or else because the medium encouraged him to rely on the well-tried methods of contrapuntal discourse which were linked to his previous style.

The chromatic language shows a considerable advance over that of the work’s predecessor, however, and if the opening subject is related in its smoothly flowing phrases and in the unclouded diatonicism of its top line to Bridge’s earlier manner, the tightly organized chromatic part-writing that supports it, while lacking the acute tensions of later years, marks a new complexity of thought.

There is still a tendency to make spacious and practically unvaried counterstatements – the first movement’s second subject is typical – but there is also a new inclination to develop and vary when repeating. Again, textures throughout the quartet are motivically saturated in a way that presages his late style, and thematic evolution and integration are developed to a new pitch. Thus, the insistent triplets of the scherzo’s main subject evolve new subsidiary themes which in their turn are transformed into the tenderly lyrical andante of the trio, while the finale remains unsurpassed for its preoccupation with by now familiar processes.

A wistful molto adagio preface which totally transforms the first movement’s second subject launches, in a moment of magical sonority, one of Bridge’s sonata arch-forms. All the principal themes can be traced back to previous material and the two main subjects are combined in counterpoint immediately before the final coda. This brilliant movement, with its unbroken flood of ideas varied by contrasting colors and textures, represents the kind of music Bridge must have been working towards for years, and the Second String Quartet as a whole can be accounted one of the composer’s finest achievements.

The first work to show Bridge’s late manner in full flight, all impurities filtered out, the implications of his recently framed ideas completely realized, is the Third String Quartet. Completed in 1926, this is music which approaches the world of the Second Viennese School in its radical procedures, while remaining utterly personal in tone.

The first movement’s first subject is typical of the kind of energetic lyricism in which the quartet abounds: the sense of linear growth is as strong as ever, but the subtle web of tensions which binds the dislocated phrases together is far removed from the old flowing cantabile, as is the way in which all 12 chromatic notes are kept in play.

In the vertical aspects of his textures, Bridge approaches a Schoenbergian pantonality, but the lack of semi-tonal dissonance in the chord-spacing and the tendency to select whole-tone and dominant formations gives an individual flavor. Harmonies of this kind are found in the middle-period works, but the speed with which they are now juxtaposed, and the freedom of the linear writing, dictate a totally different logic and create a new sound-world.

The harmonic texture is further extended by the introduction of less orthodox chord structures. The superimposition of tritones and fourths favored by the Viennese School becomes a new characteristic, as do tense Bartokian chords formed from interlocking major and minor thirds.

The structure of the quartet’s three movements shows an increasing richness and complexity of thought, and main material often appears after a period of assembly and preparation, as in the first movement’s slow introduction. Formally, the whole work is dominated by modifications of the sonata principle – arch-shaped in the first movement and with a rondo refrain in the finale. (It is indicative of the fertility of Bridge’s invention that the abundance of material in the finale still leaves room for additional development of the main first-movement themes.)

An examination of the micro-structure of the quartet reveals startling facts for an English work of the 1920s. Like Schoenberg before him, Bridge realized the significance of a pervasive motive working as a support for the developing argument in the absence of orthodox tonality. He extended the principle to the point of integrating vertical and horizontal aspects of the music, and tracing the motive connections between successive phrases and incidents in the work. One is irresistibly reminded of the tightly packed motive development in pre-12 note works by Schoenberg and Berg.

The elaborately figured and combative energy of the Third Quartet’s outer movements, and the sad, uneasy half-lights of its central intermezzo, inform much of the work of Bridge’s maturity, and the Fourth Quartet (1937), perhaps the peak of his writing in the oeuvre, resembles its predecessor in several respects.

There is a similar vein of lyrical energy, and the central movement is again a wistful intermezzo. But it is now in the finale that a slow introduction leads, via an assembly of motives, to a definitive thematic statement, and its rondo structure presses to a conclusion of hard-won optimism, contrasting with the melancholy into which the Third Quartet descends. In more general terms, the language has moved away from the expressionist richness of its predecessor: a more classical vision is outlined by the concentrated statements, concise transitions, and increase economy of texture.

At the same time, there is room enough for lyrical growth and the first movement’s second subject can afford counter-statements, albeit in varied forms, which remind us of Bridge’s early expansive vein. There is also space for the obligatory references to the first-movement material as the work closes.

In its harmonic world the Fourth Quartet is the most radical of all Bridge’s works, and its preoccupation with the more open intervals – fourths, fifths, major thirds and ninths – gives a new textural personality, uncomprisingly dissonant and bracing. The old obsession with the interlocking thirds has left its mark, but the composer’s harmonic resources are becoming increasingly wide-ranging, and the masterly way in which he saturates the texture of the finale with fifths, the interval of optimism and tonal orientation, using overtone structures to suggest a high norm of polytonal dissonance, typifies the new freedom.

The quartet’s opening sonata structure is far more concise than its counterpart in the Third Quartet, yet it manages to encompass as many changes of pace, mood and texture, welding and integrating them through the fierce heat and energy of its compressed processes. Plunging immediately into a maelstrom of gritty, motivic activity, it as quickly becomes subdued for a largamente transformation before launching out animatedly once more on transitional material.

The formal compression is made possible by the extreme concentration of the motive work and the tight developmental web of the texture. In common with the general terseness of thought, the working-out section proper is short and the recapitulation literal, apart from the omission of counterstatements and movements of expansion. This leaves the way clear for the coda to broaden the movement’s formal horizon, with two brief but unerringly judged processes – a further short development of first subject material and a tender postlude which neatly balances the largamente treatment of the first subject in the exposition by similarly transforming the second subject.

If the intermezzo opens in a wistful vein like that of its counterpart in the Third Quartet, the mood is soon broken up by lively bursts of grotesquerie. In fact, this quasi-menuetto, like much else in the work, is really without expressive precedent in Bridge’s music; in common with certain movements in the Viennese classical repertory it combined toughness of thought with an apparently capricious and divertimento-like manner.

The minuet and trio form, for instance, is enriched by sonata elements; there is the suggestion of a second subject in the main section, and the trio is a development of the first subject and introductory material, while the recapitulation omits the second subject but richly extends and contrapuntally works the first, including a reference to the first movement’s second subject.

Finally, a compressed structure is subtly opened out by the little semiquaver phrases that link many of the paragraphs, giving a sense of freedom and improvisatory leisure.

The finale is certainly one of Bridge’s finest achievements, a fitting conclusion technically and emotionally to a great work. Typically its rondo form is of the utmost simplicity: A-B-A-B-A, which allows the two principle subjects of the first movement to be worked into the transition to the final rondo statement without overburdening the structure. This brief return to the darker forces of the work’s opening renders the rondo theme’s final winging development the more impressive in its spiritual courage.

Brindisi String Quartet

The London-based Brindisi Quartet was formed at Aldeburgh in 1984.

Already an established name with listeners to BBC Radio 3, they are increasingly well known on the continent through their frequent overseas visits. Their growing reputation as one of Britain’s most exciting string quartets has led to many festival appearances, including Aldeburgh, where their close association resulted in a residency in 1990.

Whilst firmly rooted in the classical tradition, they are committed to exploring contemporary music and have had a number of works written for them by leading composers.

TRACK LISTING:

Frank Bridge – String Quartet No. 2 in G Minor

- Allegro ben moderato – 9:18

- Allegro vivo – andante con moto – 6:07

- Molto adagio – allegro vivace – 8:35

Frank Bridge – String Quartet No. 4

- Allegro energico – 10:32

- Quasi minuetto – 4:17

- Adagio ma non troppo – allegro con brio – 6:23

FINAL THOUGHT:

Alas, it appears the Brindisi String Quartet is no longer together (this recording was 30 years ago for Pete’s Sake!) – but at least we still have them rockin’ that 1986 photo! I wish the recording was better… recorded and not so muddled – and I really wish those liner notes above weren’t so long and BORING!

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company