Ludwig Van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Ludwig Van Beethoven (1770-1827)

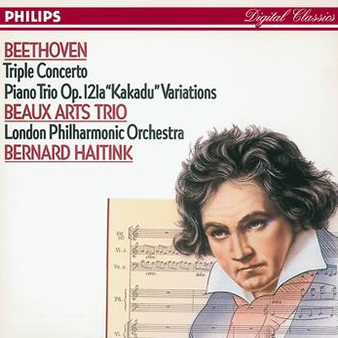

(Triple Concerto) Concerto in C for Piano, Violin, and Cello, Opus 56

Piano Trio No. 11 in G, Opus 121a

London Philharmonic Orchestra (Bernard Haitink, conductor)

Beaux Arts Trio – Menahem Pressler (piano), Isidore Cohen (violin), Bernard Greenhouse (cello)

Recorded in London 1/1977 (Opus 56); La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland 5/1979 (Opus 121a)

ONE-SENTENCE REVIEW:

I didn’t really have anything special to do on Valentine’s Day (don’t cry for me I’m going out tomorrow night – the restaurants in L.A. are a nightmare on Valentine’s Day) – so I finally have time to write this about this recording of the Beethoven Triple Concerto and… it is fabulous!

ORIGINAL LINER NOTES (by Lothar Hoffmann-Erbrecht – translation by Michael Talbot):

The Drive For Unity

Beethoven Concerto in C, Op. 56 (Triple Concerto)

Beethoven Concerto in C, Op. 56 (Triple Concerto)

Beethoven worked on the Triple Concerto during 1803-1804; it was not published, however, until 1807.

The first drafts appear already on the last pages of the “Eroica” sketchbook and are continued in the large “Eroica” sketchbook.

The concerto is dedicated to Prince Lobkowitz, but Beethoven’s later “right-hand man,” Anton Felix Schindler, claimed that this “Concertino,” as he called it, was intended for the Archduke Rudolph, the violinist Karl August Seiler, and the cellist Anton Krafft.

The same source informs us that the first performance of the concerto took place in May 1808 in the Augarten, Vienna; the concert that featured it belonged to the series that Mozart had inaugurated in 1782.

The audience’s reception was frosty; according to Schindler, the unnamed artists who performed it (and thus indirectly also Beethoven) “earned no applause at all, for they had taken the affair too lightly.” Schindler goes on: “It (the concerto) remained undisturbed until 1830.”

When, at the beginning of the present century, Hugo Riemann revised the third edition of Thayer’s five-volume biography of Beethoven, he identified the Triple Concerto as a descendant of the sinfonia concertante, widely cultivated between 1770 and 1790, in which one or more instruments from the orchestra are treated in a solo fashion.

Even without considering the fact that the piano was never thrust into the foreground at that time, Beethoven’s Op. 56 seems to find a more natural home among the new concertante literature in “chamber music” style of the early nineteenth century, where in addition to the principal instrument – in our case the piano – the other instruments are all given rewarding solos to perform.

The genre constituted by compositions identified simple as “concertante” enjoyed universal popularity in Beethoven’s time and was rarely absent from the many public concerts given by travelling virtuosi.

After 1800 Beethoven inclined, in his instrumental compositions, towards share thematic and dynamic contrasts; but on the other hand he also favored a unitary approach to cyclical works, which ultimately, as in the Triple Concerto, leads to the presence of strong motivic links between all the movements.

After 1800 Beethoven inclined, in his instrumental compositions, towards share thematic and dynamic contrasts; but on the other hand he also favored a unitary approach to cyclical works, which ultimately, as in the Triple Concerto, leads to the presence of strong motivic links between all the movements.

The opening motive in characteristic rhythm, which rises up in the bass instruments and is repeated one scale degree higher, is the kernel from which all the subsequent musical thoughts of the work grow, sometimes so directly that they become hard to distinguish.

For instance, the second theme of the opening Allegro is more notable for the contrast introduced by its dynamic, compulsively modulating development than for its outline. Its structure allows the three instruments to play about with it in manifold ways and even to anticipate the “alla Polacca” finale in the minor-key transformations, which one might well described as “all’Ungherese.”

In the Largo second movement Beethoven transposes the germinal theme to A flat major. Here a broad, freely developed cantilena again eschews contrasts and leads directly into the last movement.

This Rondo alla Polacca in the traditional triple metre harks back to the opening both motivically and formally. As in the first movement we are treated to a minor-key episode, which gradually unfolds dynamically.

Beethoven – Piano Trio No. 11 in G, Op. 121a

Beethoven – Piano Trio No. 11 in G, Op. 121a

Although by 1811 Beethoven had already almost “wrapped up” his creative legacy in the genre of the large-scale piano trio in several movements with Op. 70 and the B flat trio Op. 97, he returned once more to the fount of his artistic strivings in 1816 with the variations on “Ich bin der Schneider Kakadu” (Op. 121a).

Like the variations for piano trio on themes by Mozart from his early period, the “Kakadu” Variations are based on a simple, trifling song-theme, which he took from Wenzel Muller’s then very successful opera “The Sisters of Prague.”

Nonetheless, the differences from the early compositions are unmistakable: the structure has been loosened, and the freely flowing counterpoints and urgent, intense musical language used in the gradually expanding forms betray the proximity of the last piano sonatas and the “Diabelli” Variations from the same year.

The set of variations opens with an Adagio assai in G minor, an introduction that, despite being thematically related through its concentrated, shifting harmony, still conceals its aim. Only then do we hear from the trio the merry, trilling theme in the style of a Singspiel.

The first variations initially proceed along traditional paths, allowing the instruments to come into prominence in turn and slowly building up to a climax with changing figurations.

The music grows ever more complex, develops into fugato (variation 5) and fugue (variation 7) and introduces strong contradictions which develop in broad forms (variation 9: Adagio espressivo).

The tenth and last variation begins as a gigue, then recalls its G minor middle section the harmony of the introduction, and finally, in a viruoso coda, dissolves the outline of the restated opening Allegretto theme in a whirl.

The tenth and last variation begins as a gigue, then recalls its G minor middle section the harmony of the introduction, and finally, in a viruoso coda, dissolves the outline of the restated opening Allegretto theme in a whirl.

The course of this work once again demonstrates in a nutshell how Beethoven found an individual way forward from the mechanical type of variation of the eighteenth century to the character variation on which he set his stamp.

TRACK LISTING:

- 1: Beethoven Concerto in C (Triple Concerto) – Allegro [18:03]

- 2: Beethoven Concerto in C (Triple Concerto) – Largo, Rondo alla Polacca [18:24]

- 3: Beethoven Piano Trio No. 11 in G, Op. 121a [19:01]

https://youtu.be/dS8CkxkQ-YE

https://youtu.be/RfocptSpsYA

FINAL THOUGHT:

So the audience hated the first performance of the Triple Concerto so much that it wasn’t played again for 23 years. Man, have our standards become so low that this bum Beethoven somehow became a genius over the years – or is our knowledge of classical music so limited that anything by anyone from a couple of hundred years ago is considered great because we’re afraid any criticism would show our ignorance? My vote goes to Beethoven is a genius and that opening night audience in 1808 were a bunch of idiots.

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company)

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company)