Benjamin Britten (1913-1976)

Young Apollo For Piano, String Quartet and String Orchestra (1939)

Double Concerto For Violin, Viola and Orchestra (1932)*

Two Portraits For String Orchestra (1930)*

Sinfonietta (Version For Small Orchestra) (1932)

———————

Gideon Kremer, Violin

Yuri Bashmet, Viola

Nikolai Lugansky, Piano

Halle Orchestra

Kent Nagano, Conductor

Recorded Bridgewater Hall, Manchester, February 1998

* World Premiere Recordings

———————

ONE-SENTENCE REVIEW:

To read the recording notes you would think this recording of Benjamin Britten early works was nothing more than ‘shite’ from a composer that was, eventually, going to be great – but these are really interesting pieces that deserve to be heard more.

ORIGINAL LINER NOTES – Colin Matthews

Benjamin Britten – The Young Apollo

These recordings document an extraordinary period of innovation and experiment from Britten’s early years; two of the works predate his Opus 1, the Sinfonietta, and were never performed in his lifetime, and one, Young Apollo, was withdrawn shortly after its first performance.

Britten was remarkably prolific as a young composer, and many of the works from this time were put aside to await revision or completion as he rushed on to the next piece.

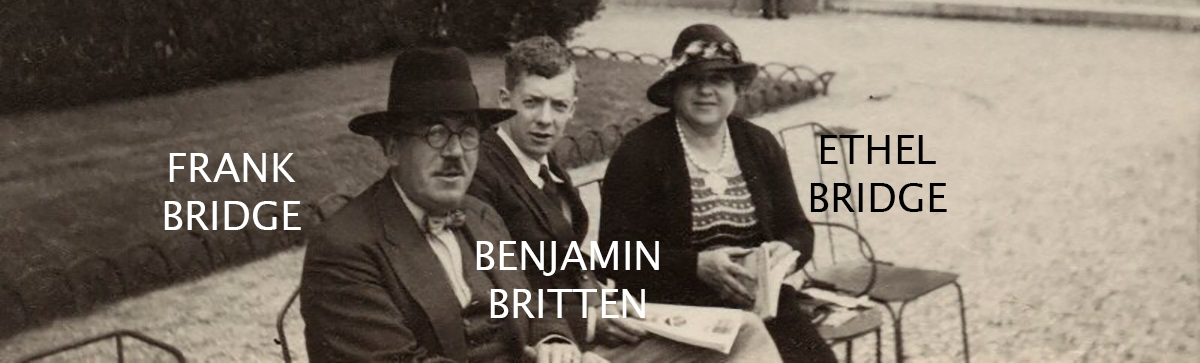

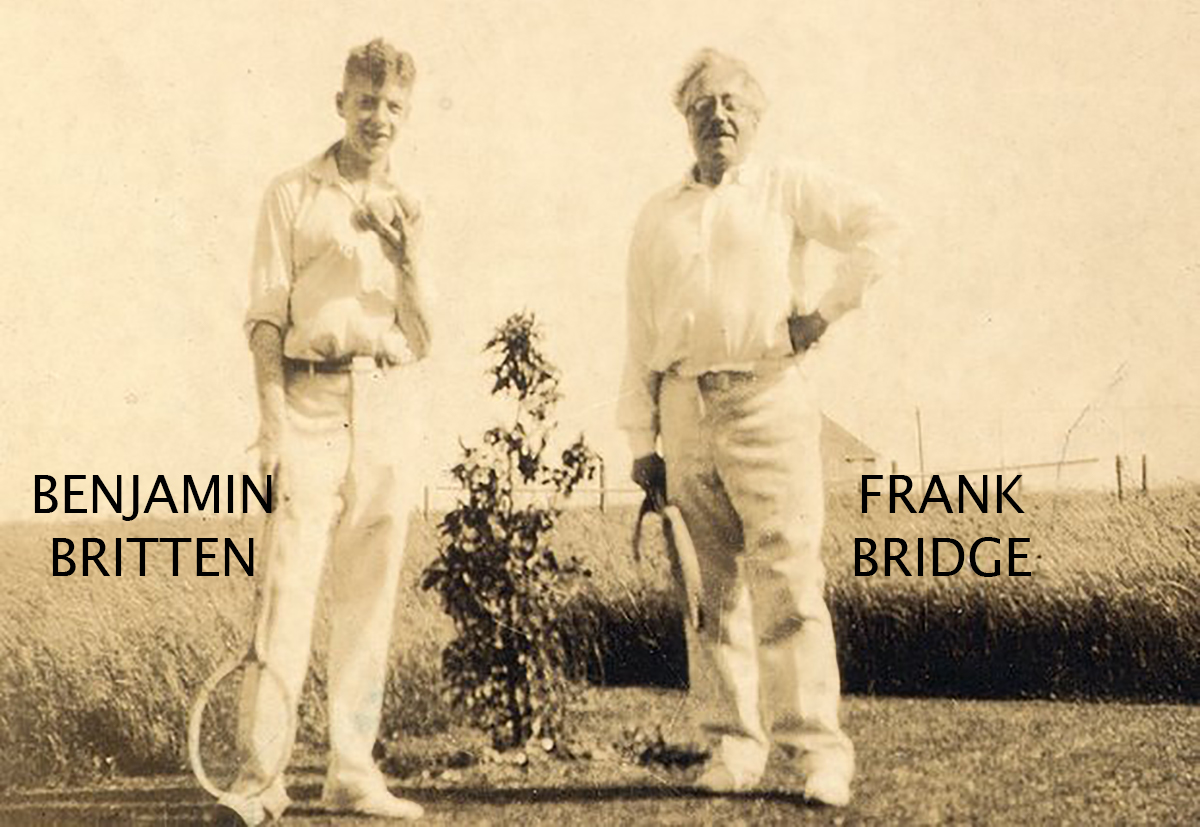

From 1928, when he was fourteen, Britten studied privately with Frank Bridge (1879-1941), before going to the Royal College of Music in the autumn of 1930.

He began writing the Two Portraits in August 1930 shortly after leaving school. One of his closest school friends had been David Layton, who is depicted in the first Portrait (Britten’s manuscript title is ‘Sketch for strings‘).

The second Portrait has the subtitle ‘E.B.B,’ Britten’s initials, and it is clearly a self-portrait, with the viola (his own instrument) taking the lead role.

A third movement was planned but was not written; probably there was not time before Britten started his academic studies.

The first Portrait is a highly-chromatic and intense piece, rhapsodic in character, but introducing a strange waltz-like lilt shortly before the remarkable coda, in which solo strings bring back the opening of the work over a distance C major chord.

The second Portrait is strikingly different; a gentile and deeply-felt melody over a simple accompaniment.

During his first year at the Royal College, Britten wrote mainly vocal music, although he completed a D major String Quartet which he was to revise and publish in 1974.

From the autumn in 1931, he began to concentrate on instrumental and orchestral works (including two large-scale ballet scores), beginning work on the Double Concerto in May of 1932.

He interrupted it to compose the Sinfonietta (in no more than three weeks!), but completed the Concerto in sketch by the early autumn. Although the sketch is very detailed, he never made a full score, and seems to have made no attempt to get the work performed.

He showed it to his teacher at the College, John Ireland(1879-1962), who, as Britten recorded in his diary, was ‘pretty pleased’ with it. But it seems quite likely that his experience in rehearsing the newly completed Sinfonietta with a student orchestra in the autumn of 1932 (‘I have never heard such an appalling row!’ read another diary entry) discouraged him from going on to complete the Double Concerto in score.

He was not, in fact, to hear any of his orchestral music until the first performance of Our Hunting Fathers four years later.

The Double Concerto was first performed at the 1987 Aldeburgh Festival, with Kent Nagano conducting.

Since the composition of the Concerto and the Sinfonietta was so intertwined, it is not perhaps surprising that they follow the same formal plan; a vigorous opening movement, and a Tarantella Finale.

The Concerto, although substantially the larger of the two pieces, is perhaps less adventurous in style (the first movement of the Sinfonietta is strongly influenced by Schoenberg’s 1906 Chamber Symphony). Clearly the highly virtuoso writing of the soloists parts led Britten towards more conservative orchestral textures.

However, the dance-like Finale and sudden and unexpected return at the end to the music of the first movement are as original as anything he had written to date, and the work stands as an outstanding achievement for an eighteen-year-old.

The Sinfonietta’s more concentrated writing for its original ten players reveals a determined effort by Britten to write an ‘Opus 1,’ which would make a mark on the musical world.

Although its first performance in 1933 received a mixed reception (for many years the critical establishment tried to dismiss Britten as ‘too clever by half’), his position as the leading British composer of his generation was established from that point on.

In 1936, he made what he called an ‘orchestral’ version with a part for second horn, and indications for string orchestra rather than solo players. But although it received a performance at the time, the only score in which Britten wrote this version was left in the USA after his return home in 1942, and did not reappear until the 1980s.

The annotated score is a particularly fascinating document as on the flyleaf are two poems of W.H,. Auden, written out for Britten in January 1937 by the poet just before his departure for the Spanish Civil War.

Auden’s departure for America in 1939 was the catalyst for Britten’s own move there in April of that year. His initial reception as composer and pianist in the USA and Canada was so enthusiastic that he contemplated a long stay, if not permanent residence.

By the summer he already had his first commission from the Canadian Broadcast Corporation in Toronto, for a ‘Fanfare’ for piano and orchestra. Britten wrote in a letter that it is founded on the end of [Keats’ unfinished poem] Hyperion ”From all his limbs celestial’... It is very bright and brilliant music – rather inspired by such sunshine as I’ve never seen before.’

Young Apollo was broadcast live by CBC in August 1939 with Britten as soloist; after a subsequent broadcast from New York in December, Britten withdrew the work, and it received no further performance until 1979. Yet he had given it an Opus number (16) and had seemed pleased with it.

Experimental in a wholly different way from his early music, Young Apollo is an extraordinary Fantasia composed entirely – with the exception of the piano’s scales in the cadenza near the beginning – in A major.

Britten seems almost to have anticipated minimalism with this work: did he think he had, for once, gone too far?

TRACK LISTING:

Benjamin Britten (1913-1976) – Young Apollo, Opus 16 (1939)

- Moderato – Allegro Molto – 7:06

Benjamin Britten – Double Concerto in B Minor (1932)

- Allegro ma non troppo – 6:03

- Rhapsody, Poco lento – 7:25

- Allegro scherzando – Allegro non troppo – 8:03

Benjamin Britten – Two Portraits (1930)

- No. 1 – ‘David Layton’ for string orchestra – Poco presto – 9:10

- No. 2 – ‘E.B.B.’ for solo viola and string orchestra – Poco lento – 5:43

Benjamin Britten – Sinfonietta, Opus 1 (1932)

- Poco presto ed. agitato – 4:16

- Variations, andante lento – 6:16

- Tarantella, Presto vivace – 4:04

FINAL THOUGHT:

Even today, Benjamin Britten is still being discovered and though it took 60 years (!) for a couple of these works to get a recording, it was worth the wait (Note, this was recorded in 1998.). This is a nice group of early Britten pieces and worth a listen. Here’s hoping BB gets the same kind of renaissance that Shostakovich received in the late 1990s which continues to this day! (Note, for good reason – he’s fucking awesome!)

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company