Anton Stepanovich Arensky (1861-1906)

Anton Stepanovich Arensky (1861-1906)

String Quartet No. 1 in G Major, Op. 11

String Quartet No. 2 in A Minor, Op. 35

Piano Quintet in D Major, Op. 51

Ilona Prunyi – Lajtha Quartet

Recorded at the Rottenbiller Street Studio, Budapest from January 16 – 22, 1994

ONE-SENTENCE REVIEW:

Sometimes, even though you wash your hands over and over again, you just can’t get the stink out – that’s how I feel about the Arensky String Quartets – I want them to be clean and smell good but every time I listen to them, I can’t get the stink out. (I realize that should be three sentences but I used dashes instead to preserve my one-sentence format – sorry.)

ORIGINAL LINER NOTES (by Keith Anderson):

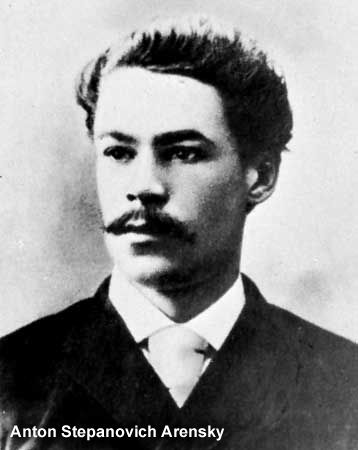

The son of keen amateur musicians, his father a doctor, Anton Arensky was born in Novgorod in 1861. His musical abilities were encouraged by his parents and he had his first piano lessons from his mother.

As a child he had begun to write music and when the family moved to St. Petersburg he was able to take more consistent musical instruction and after some preparation, in 1879 to enter the Conservatory, where his teachers included Rimsky-Korsakov for composition and Johannsen for counterpoint and fugue.

As a child he had begun to write music and when the family moved to St. Petersburg he was able to take more consistent musical instruction and after some preparation, in 1879 to enter the Conservatory, where his teachers included Rimsky-Korsakov for composition and Johannsen for counterpoint and fugue.

He was entrusted with the preparation of a piano reduction of the former’s opera The Snow Maiden and under Rimsky-Korsakov’s supervision began work on his own first opera A Dream on the Volga, which was later completed, to be staged in Moscow with some success in 1891.

His teacher, however, saw no great future for the works of his pupil, considering any success achieved likely to be transitory. This prediction has not proved true in every respect, since some, at least, of Arensky’s works have maintained a secure if limited place in standard orchestral and piano repertoire.

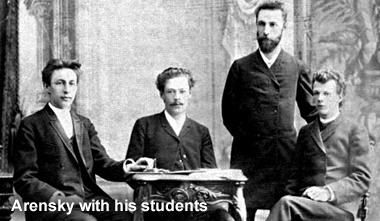

Arensky completed his studies at the Conservatory in 1882 and at once took up a position at the Moscow Conservatory as a teacher and later as professor of counterpoint and harmony. There his pupils included Rachmaninov, Gliere, Conyus and Scriabin, and there was fruitful contact and friendship with Tchakovsky and Taneyev.

He appeared as a conductor at concerts, notably of the Russian Choral Society, and his connection with church music led to his appointment, on the recommendation of Balakirev, as director of the imperial chapel in St. Petersburg, a position he took up in 1895 and held until 1901.

His final years left him free to follow a career as a composer, pianist and conductor, brought to an end in part through his dissolute way of life. He died of tuberculosis in 1906 at the age of forty-five.

His final years left him free to follow a career as a composer, pianist and conductor, brought to an end in part through his dissolute way of life. He died of tuberculosis in 1906 at the age of forty-five.

In style and technique Arensky owed much to his teachers. He developed a sure command of harmonic, contrapuntal and structural musical resources, with a lyrical facility.

These elements are at once apparent in his String Quartet No. 1 in G major Opus 11, written in 1988. This shows, from the first bars, an easy understanding of the medium of the string quartet and of the possibilities still inherent in the traditional first movement form.

The second movement opens with a melody of fine contour, before a contrapuntal element is introduced by the cello, followed by the other instruments, and a treatment of the principal melodic material with more elaborately contrapuntal accompaniment.

The mood changes with a light-hearted Menuetto and contrasting Trio.

A Russian element makes its appearance in the Finale, with its variations on a Russian theme. These bring their surprises, not least in the traditional folk texture suggested by the plucked accompaniment in one variation and the later fragmentation of the theme, before a cadenza and the return of the theme in a mood of mounting excitement, leading to an emphatic and vigorous conclusion.

Arensky’s String Quartet No. 2 in A minor, Opus 35, was written in 1895 and in its first movement presents a more somber atmosphere, lightened by secondary material, dramatically developed, but returning to its initial mood.

Arensky’s String Quartet No. 2 in A minor, Opus 35, was written in 1895 and in its first movement presents a more somber atmosphere, lightened by secondary material, dramatically developed, but returning to its initial mood.

The theme of the second movement is stated simply, before its elaboration in a series of variations with the theme taken by each instrument in turn, before the possibilities of plucked strings and further textural resources are explored in a spirit that ventures far from the original material, sometimes with the energy of a scherzo, then relaxing into a gentler lyrical and eventually somber mood.

The third movement continues in its opening bars the Russian idiom, already heard in the theme of the second. The introduction is followed by what promises to be a vigorous fugue, on a Russian subject, superseded by a reminiscence of the melancholy of the opening of the quartet and followed by an energetic and triumphant conclusion.

The Piano Quintet in D major, Opus 51, was written in 1900.

The piano starts the first movement, soon joined by the string instruments in a historic opening of a texture that recalls that of Schumann’s Piano Quintet. Here, too, the piano plays a virtuoso part, whether in accompaniment or in the statement of thematic material.

The second movement is again in the form of a theme and variations, the former entrusted first to the strings, before the lyrical intervention of the piano, followed by a turn to the more dramatic, a change of mood to the solemn and then to the lyrical. The piano moves on to a recreation of Chopin, in romantic partnership, and then to music of greater vigor, subsiding into the language of the opening.

The capricious Scherzo breaks in, interrupted in its turn by a peaceful trio that brings momentary serenity here and when it returns after a repetition of the Scherzo, which itself has the last word.

A subject of Baroque contour introduces the last movement fugue, but the rigors of counterpoint are later submerged in a thoroughly romantic conclusion.

TRACK LISTING:

- 1-4: String Quartet No. 1 in G Major, Op. 11

- 5-7: String Quartet No. 2 in A Minor, Op. 35

- 8-11: Piano Quintet in D Major, Op. 51

FINAL THOUGHT:

Look, I’m not going to slam Arensky too much here (he got enough of that in his life from the asshole Rimsky-Korsakov) but considering he was living a pretty wild life away from work (gambling, drinking like a fish, etc. etc.) the String Quartets are pretty boring. I’ll cut the Piano Quintet a little more slack because I just love piano quintets as a genre (for my money, there is nothing much better than the Shostakovich Piano Quintet – which I’ll get to in about two years!). Unfortunately for Arensky and his legacy – these are works you just don’t want to listen to that much.

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company)

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company)