Anton Bruckner (1824 – 1896)

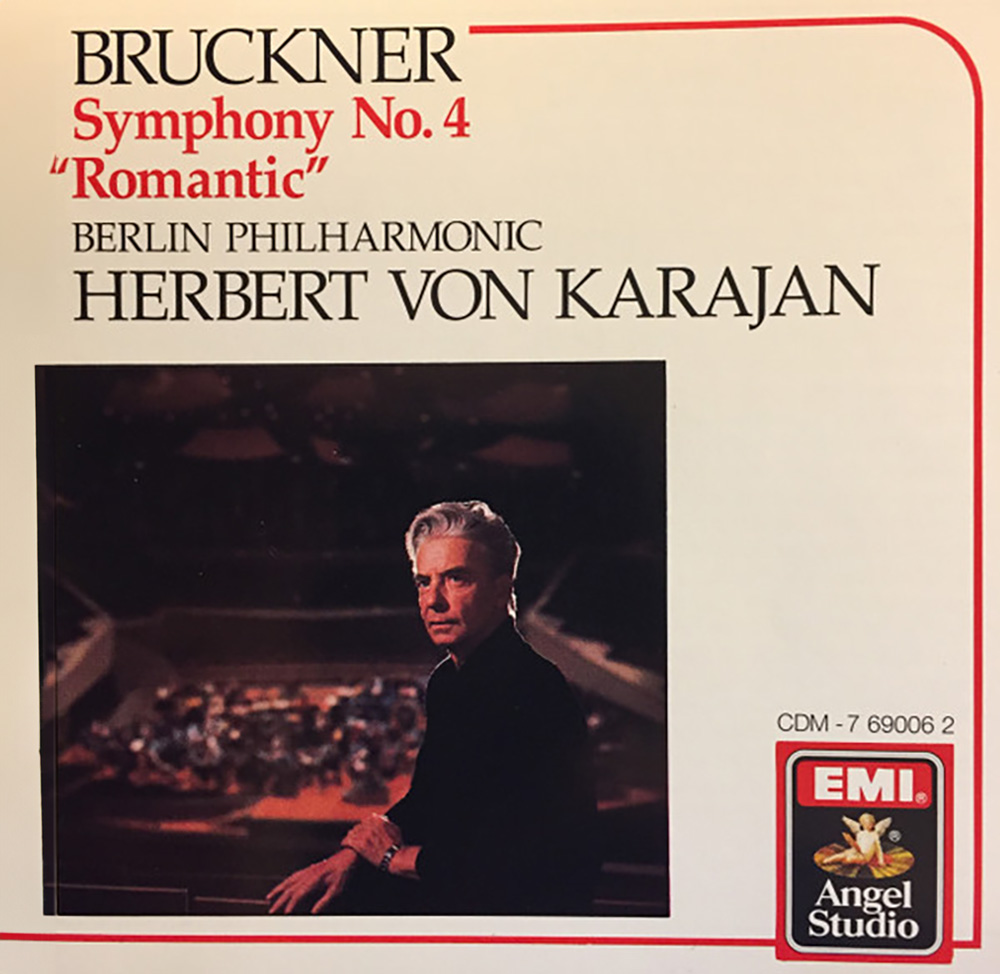

Symphony No. 4 in E-Flat Minor ‘ Romantic’

———————

Herbert Von Karajan, Conductor

Berliner Philharmoniker

Recorded 1970, Jesus Christus Kirche, Berlin, Germany; Remastered 1987

———————

ONE-SENTENCE REVIEW:

I mean, it’s Bruckner, it’s von Karajan, and it’s the Berliner Philharmoniker… what could go wrong? Not much.

ORIGINAL LINER NOTES by Peter Branscombe, 1985

Bruckner wrote his Fourth Symphony in 1874, but between 1878 and 1880 he revised it twice, completely replacing the scherzo and finale. In its new form the work was successfully performed at a Vienna Philharmonic concert under Hans Richter on February 20, 1881. The symphony was nevertheless subjected to further reworkings in 1886 and 1887-1888, but it is in the 1878-80 version that it is normally heard.

I. Bewegt, nict zu schnell: Over shimmering ppp strings there rings out the horn-call that will dominate the first movement and return at the end of the finale. With a typical two-plus-three rising figure Bruckner introduces his second thematic complex. A sonorous tutti gives way to a woodbird call in the violins.

The development ranges from the quietest of woodland musings to the full roar of striding tutti and resonant chorale, and the recapitulation creates the impression of a familiar landscape viewed from a new vantage point. Though the coda steals in quietly, even menacingly, this is to be a passage of the utmost splendor.

II. Andante quasi Allegretto: Although the typical Bruckner Adagio lies in the future, there is a solemnity about this lovely movement that on its own terms is quite as impressive.

Cello cantilena, a quiet chorale and a beautiful viola melody prove the principal material for this boldly modulating, questing movement. The principal theme is heard for the last time in the coda. Then, after a powerful climax, the movement dies away with tonic and dominant timpani-taps and pizzicato chords.

III. Scherzo – Bewegt: There is no precedent for the splendid ‘hunting’ Scherzo which – along in Bruckner’s symphonies – is in 2/4 rather than 3/4 time.

In two-plus-three rhythm the horns launch their calls ever more intensely above hazy strings; the heavy brass join in before a gentler string response, but there are also eerie phrases to come. The Trio, Nicht zu schnell, Keinesfalls schleppend, presents a magical period of calm; the sudden shift back to the reprise of the Scherzo is an exciting moment.

IV. Finale: Bewegt, doch nict zu schnell: The movement opens in an ominous B-flat minor, with clarinets and first horn enunciating a falling three-note figure which will become important at the first tutti, where it is answered by the two-plus-three note-pattern that has already been remarked on.

This powerful paragraph (it looks back to the theme of the Scherzo and the rhythm of the opening movement) closes in a firm E-flat; a drop in tempo users in the second subject on the upper strings, in C minor.

The C major theme that comes next is almost vacuous by comparison, and what follows reveals that Bruckner has not yet attained full master of the symphonic finale.

The coda, however, is a wonderful achievement; horns emerge from a wash of woodwind to stride purposefully towards a majestic final peroration.

_______________

TRACK LISTING:

Anton Bruckner (1824 – 1896) – Symphony No. 4in E-Flat Minor – ‘Romantic’

- Bewegt, nicht zu schnell – 20:37

- Andante quasi Allegretto – 15:28

- Scherzo: Bewegt – Trio, Nicht zu schnell, Keinesfalls schleppend – 10:33

- Finale: Bewegt, doch nicht zu schnell – 23:02

FINAL THOUGHT:

Don’t like the piece? Fine. Don’t really like Bruckner? Okie-dokie. But this performance cannot be denied. A perfect match of music, conductor and orchestra.

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company