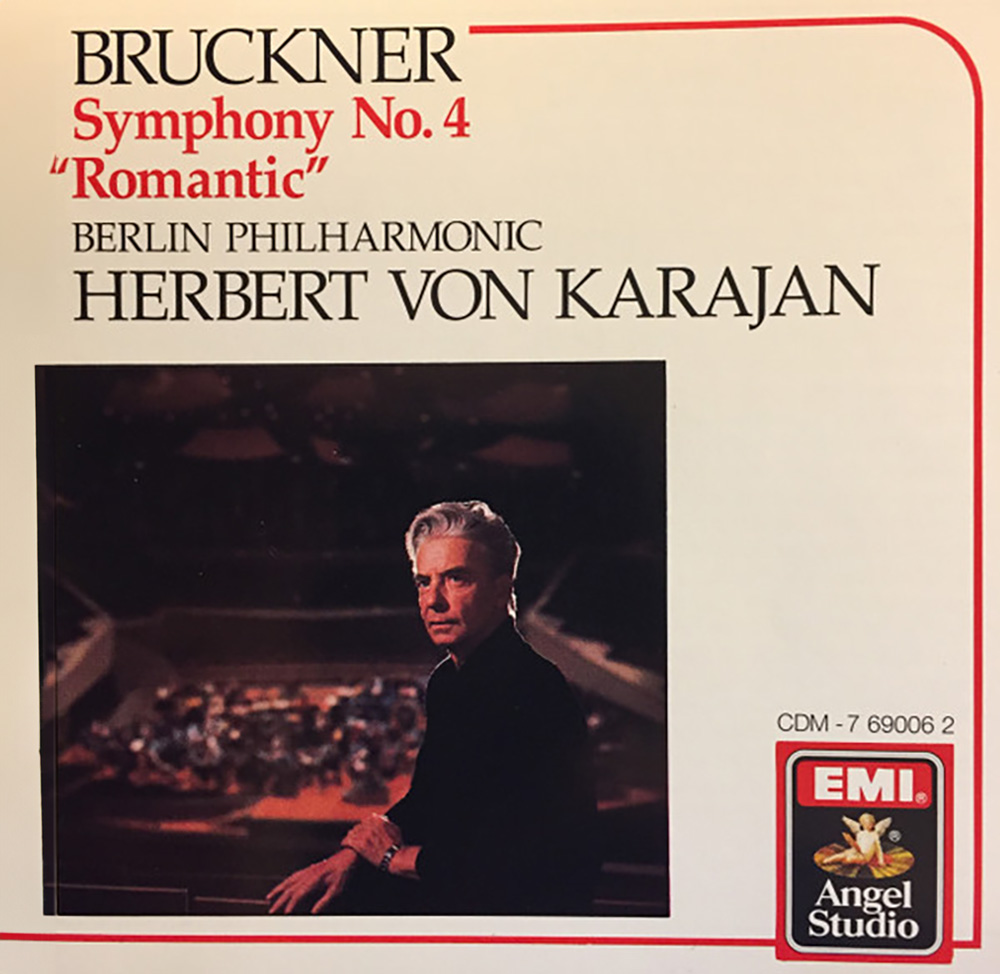

Anton Bruckner (1824 – 1896)

———————

Herbert Von Karajan, Conductor

Berliner Philharmoniker

Recorded April 1975, Berlin

———————

ONE-SENTENCE REVIEW:

I mean, it’s Bruckner’s Seventh – who can screw this up – certainly not Herbert Von K!

ORIGINAL LINER NOTES by Richard Osborne, 1975

The Seventh Symphony is perhaps Bruckner’s most perfectly wrought work, his richest, most luminous utterance.

It was begun with the Scherzo in 1881, droll, dancing and humane. Then in 1882, under the spell of Wagner’s Parsifal, Bruckner began work on the beautiful first movement, a movement of aspiring eloquences whose principal theme, the composer tell us, came to him (scored for a viola) in a dream.

The Adagio is said to have been written under the influence of a premonition of Wagner’s death; indeed, its coda, a profound and solemn threnody, was redrafted when news arrived from Venice on February 13, 1883, of the Master’s passing.

Completed later in 1883, the Symphony received its first performance under Arthur Nikisch, in Leipzig on December 30, 1884. The work was dedicated, not to the memory of Wagner (Bruckner invariably chose living dedicates, among whom he numbered Almighty God), but to Wagner’s patron, King Ludwig II of Bavaria.

It was well liked, and as the revised autograph was used by the printers of the first edition, it offers a rare example in the Bruckner canon of a clean text, through the anonymously scrawled phrase ‘gilt nicht’ (not valid) over the timpani, triangle and cymbal at the Adagio’s ecstatic climax has excited controversy. The cymbal was probably Nikisch’s idea; but cymbal clashes are not necessarily banal. They can be emblems of light and divine revelation, as Wagner himself shows in the Prelude to Lohengrin.

Certainly most eminent Bruckner conductors see fit to include the cymbal, ‘valid’ or not. Some editions (but not Robert Haas) also include meddlesome tempo markings which, along with other ‘traditional’ effects, can, if followed, seriously detract from the movement’s single vision. But this is not a problem which need detain us in this set. Karajan’s whole, luminous way with the later Bruckner symphonies is well known – has, indeed, been one of the glories of the European musical scene for four decades.

The theme that launches the Seventh Symphony is one of the loveliest, and longest, Bruckner ever wrote; a glorious, sweeping melody on the cellos spanning two-octaves.

Always longer than one remembered, it sweeps down, up and and across; hill, valley and a whole ample landscape beyond. As one paragraph ended, another begins, even more serene, the eye now travelling upwards and outwards from the earth – one of the most beguiling and characteristic tricks of romantic landscape art, with its love of sweeping vistas and intimations of immortality beyond.

A second them in B major on oboes and clarinet, and recognizable by its discreet ‘Wagnerian’ appoggiatura, intrudes, adding a different kind of radiance, a deeper distance, to the music and it, too, is answered with quiet ecstasy.

But, as so often in Bruckner, a pizzicato figure brings new life; a climax is gestated, itself gestatory, for from it a third and finale theme is born; a naive dancing motive in fustian octaves, not unlike the germ cell of the first movement of Beethoven’s ‘Pastoral’ Symphony, though more home spun.

Climaxes in the Seventh Symphony are rarely climactic as they are in the Eighth. A triple forte arrives, but it strikes no terror in our hearts and leads to one of Bruckner’s most spacious meditations, the page almost bereft of notes.

Only the eye perceives the V-shape of the opening theme spread by the clarinets, while the oboe arches above (a shape which will usher in the movement’s coda) and the trombones cluster beneath, a humped, rock outcrop. Twice the rustic third theme fits across our view high on the flute, until the flute, finding voice, undergoes a symbolic transformation – becomes a a dove descending, ushering in a passage for cellos (soon to be gloriously extended) which recalls Parsifal and the mysteries of the Grail.

The third subject returns, the basses, mocking, inverting it step by step until it steals away in an elfin motion on the solo flute. Another climax bursts, full of striding V-formations. But serenity is the movement’s keynote and the next climax, after an arcane and (for this Symphony) surprisingly long recapitulation-cum-development, rides in, aptly enough, on the dancing third subject.

Out of the ensuing silence part of the movement’s opening theme emerges; then a bridge passage of great harmonic beauty; and finally, the coda peacefully, radiantly ushered in by the chameleon flutes while, beneath, tremolando strings conjure an ecstatic ground swell and the brass prepare to resound the great movement proudly home.

The Adagio begins with a glorious, imposing utterance on violas and Wagner tubas in a key, C sharp minor, skillfully avoided until now. Then, in the fourth bar, a second theme appears in the strings, a deep-throated hymn similar in outline to the ‘non confundar’ of the Te Deum.

A long, undulating, contemplatively beautiful extension of the strings main subject leads to a short climax from which violins and clarinets sweep solemnly down to horns and tubas poised on the second subject’s very edge.

The subject, when it comes, is something of a surprise; one of Bruckner’s most winningly accessible melodies floated off the beat, graciously in 1/4 time in the courtly and chivalrous key of F-sharp.

The opening measures return, still in C-sharp minor and even more massively impressive, until the music, sweeping onwards and upwards, reaches a C major climax and a wonderful series of stark, antiphonal statements – flutes and oboes, horns, sotto voce strings and, finally, trombones erecting keys like royal standards before the regal G major climax is bowed nobly in.

Bruckner’s slow movements could often end halfway through, so marked in the mid-way caesura. But the second subject now returns in fantastic guise, the first violins wreathing laurel leaves in its hair. Again, the music pauses, but a brief transition leads us more swiftly than we dared imagine into a reiteration of the tubas’ solemn theme.

This time, though, the strings’ caressing motion tells of imminent apotheosis. Wave upon wave of sound – as glorious a preparation as Bruckner ever penned – lead us to the disputed climax; C major, triangle, timpani and resounding cymbal giving out, with the full orchestra, a climactic triple forte.

The coda, by contrast, is cavernous and grand; a eulogy to the dead Wagner, with one magnificent horn crescendo and an octave fall of the violins’ C sharp that unburdens the soul. In a sense, this grand movement seems no longer than a slow movement by the mature Mozart – a tribute to the profundity and reach of Mozart’s music; but a tribute, too, to the depth and succinctness of Bruckner himself, who even in this majestic Symphony remains decisively within the pale of the greatest of all symphonic traditions.

The Scherzo is gloriously all of a piece, with its steadily dancing motive rhythm and the proud cock-crow of the trumpets (the familiar description – though whether cocks crow in such exemplary fourths, fifths and octave leaps must be a matter for ornithological verification).

The dipping string theme nine bars in has to English ears, something of an Elgarian feel to it. The Trio, by contrast, is a rich song of summer, quarried from the Scherzo’s opening pulse, beginning in F major but moving radiantly beyond before its nostalgically songful returns.

That the darting opening theme of the Finale is related to the Symphony’s opening is an interesting, if somewhat academic, point. More significant is its terse ‘humorous’ quality (Haydn could have used it). Rather more familiar ground is reached in teh second subject, a lovely broad chorale, complete with Wagnerian appoggiatura and the familiar stalking Bruckner bass. And to these elements a third is joined, for in a series and mock-heroic confrontations.

A minor solemnly vies with C major, and A flat major vies with both, in a quest for tonic status. At one point the violin break cover, soaring imposingly upwards, and it is only with the solemn, schoolmasterly intervention of the Wagner tubas that the debate is temporarily stilled.

From here, themes are suddenly and surprisingly inverted (a familiar Bruckner device), another battle is joined and an even bigger climax achieved, C major sailing out of the fray, after a suitably pregnant silence, with the lovely chorale (prize booty, indeed) safely stowed.

No doubt Bruckner’s humor, like Wordsworth’s, will strike many by its meagerness alone. But blunt, and quirky and abstruse as it may seem, this finale reconciles dignity and humor in a remarkable way. Brevity, they say, is the soul of wit, and this Finale (gloriously scored) is, by Brucknerian standards, brief to the point of being abrupt. But if its opening theme could indeed have been used by Haydn, and if the joyous repetitions in the coda suggest the Olympian playfulness of Beethoven at the end of his Eight Symphony, the mix as a whole remains indelibly Brucknerian.

For terse and witty as this finale is, it has – once E major reestablishes its hold upon the rock face, which it does soon after the chorale’s return – not only ebullience to its credit but a kind of cosmic sufficiency, hymning us, as only Bruckner can, with an invincible splendor.

_______________

TRACK LISTING:

Anton Bruckner (1824 – 1896) – Symphony No. 7 in E Major

- Allegro moderato – [20:06]

- Adagio, Sehr feierlich und seh langsam – [21.55]

- Scherzo, Sehr schnell – [9:50]

- Finale: Bewegt, doch nicht schnell – [12:26]

FINAL THOUGHT:

An awesome work and an incredible performance – but, man, those liner notes are so annoying and so overwritten. Still – a top notch, hall of fame worthy recording.

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company