Sonata in A minor, Wq.156 (H.582)

Sonata in F major, Wq.154 (H.576)

Sonata in E minor, Wq. 55 (H.577)

Sonata in B-flat major, Wq.158 (H.584)

Sonata in D minor, Wq.160 (H.590)

London Baroque (Ingrid Seifert – violin; Richard Gwilt – violin, Charles Medlam – cello; Richard Egarr – clavecin) (Harmonia Mundi)

ONE-SENTENCE REVIEW:

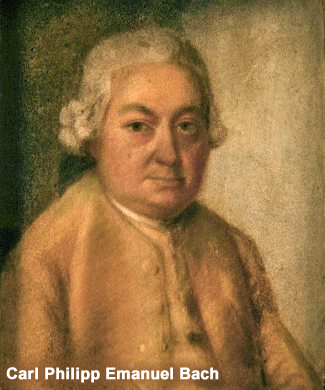

J.S. Bach had 20 children (10 survived to adulthood) – C.P.E. Bach is one of the survivors and he also composed music like his dad, just not quite as good (the chick on the CD cover pretty much says it all).

ORIGINAL LINER NOTES (by Hans-Gunter Ottenberg – translation by Derek Yeld):

One of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach’s earliest compositions was a Trio Sonata which has unfortunately been lost. I twas not without a tinge of pride that the remark, “compiled collaboration with Johann Sebastian Bach,” was added to the catalogue of Bach’s posthumously published works (1791).

It cannot be a coincidence that at the beginning of his career as a composer J.S. Bach’s second son had to come to terms with one of the most commonly practiced instrumental forms in Baroque music, considering that the Trio Sonata demanded “that there shall be all the parts, but especially in the upper voices, a steady singing line and a fugal development” (J.A. Scheibe). Moreover, the “concertante” setting-out of the Trio and particularly the techniques of the thorough-bass could be tried out in this, “one of the most difficult forms of composition.”

It cannot be a coincidence that at the beginning of his career as a composer J.S. Bach’s second son had to come to terms with one of the most commonly practiced instrumental forms in Baroque music, considering that the Trio Sonata demanded “that there shall be all the parts, but especially in the upper voices, a steady singing line and a fugal development” (J.A. Scheibe). Moreover, the “concertante” setting-out of the Trio and particularly the techniques of the thorough-bass could be tried out in this, “one of the most difficult forms of composition.”

Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach composed a total of twenty-five Trio Sonatas, seven in his Leipzig and Frankfurt periods, and the others in Berlin, mainly around 1747 and 1754.

In the worlds of the Berlin period the technical standards of the composition of the Trio Sonata, as described in a work like Sulzer’s Allgemeine Theorie der Schonen Kunste (1771-1774) had long-since been attained.

It is remarkable how C.P.E. Bach builds the theme of the first movement of the Sonata in F major, W.154/H.576 written in 1747 in the spirit of a gradual opening-up of the sound space. This shaping of the theme can probably be explained, in the first place, from the point of view of performing techniques, since they were played in Berlin by obviously accomplished violinists.

Through the use of different layers Bach achieves greater melodic variety. According to his natural tendency the main theme is kept open, that is, it wants to keep going; in the immediately following development section its motivic substance is treated polyphonically, consequently the second melodic instrument enters at the interval of a fifth.

In the Andante a more expressive mood predominates communicated to the listener by the gesture of a delicately sensitive melodic line.

In the Andante a more expressive mood predominates communicated to the listener by the gesture of a delicately sensitive melodic line.

In the last movement the motivic ideas are of such vitality that there is a change of musical scene in virtually every bar. This constant fluctuation was understood by his contemporaries as the prevalence of a rhetorical principal.

And, in fact, the opening movement of the Sonata in E minor, Wq.155/H.577, also written in 1747, does lead us into a conversational situation in which the alternation of an emotional and a gallant tone results in the domination of a dialogue-like structure.

Sulzer, in a generalization of a peculiarity of the “Berlin Bach’s” keyboard works (“Most of them are so eloquent that one does not think one is hearing tones, but a comprehensive language”), said of the Trio Sonatas that they were “veritable passionate musical conversations.”

In the slow movements, too, Bach occasionally makes use of the galant manner by indicating a faster tempo – here Andante. The concluding Allegro gives the impression of having been inspired by a dance, with its dotted motives and series of triplets arousing a cheerful mood in the listener.

The Sonata in B-flat major, Wq.158/H.584 of 1754, also demonstrates how Bach already introduces disparate expressive values within the theme itself, which then go on to mark the further progress of the movement: four bars of a plaintive motive, and four bars of triplet figures. If one were to seek the general theme of the dialogue suggested here, one could speak of a “fashionably galant expressiveness” (A. Durr).

The slow movement, Largo, con sordini, is the traditional position for a piece of musical Empfindsamkeit. All the activity is focused on the melodic line. Eloquent pauses and sudden exclamation underline the emotionally laden gesture of this movement, which once more bears witness to Bach’s sensitive handling of the variation form, for instance where he changes the direction of the movement of theme.

As in the opening movement, the concluding Allegro is also formed of heterogeneous elements: an introductory phrase that insistently turns around the note and gives rise to octave interval structures in the end phrase. And again they evoke an ambivalent expressiveness.

As in the opening movement, the concluding Allegro is also formed of heterogeneous elements: an introductory phrase that insistently turns around the note and gives rise to octave interval structures in the end phrase. And again they evoke an ambivalent expressiveness.

The manner in which Bach treats the two upper voices of the Sonata in A minor, Wq.156/H.582 (1754) shows him on the way to a new understanding of the genre.

The second voice is reduced to a mere accompanying function. It moves along in thirds and sixths beneath the melody of the top voice without intervening in its motivic construction. Occasionally it drums out the same quaver figure as the bass.

Sulzer knew this type of Trio Sonata, which is derived from the symphony and demands “an extremely charming and expressive melody in the upper voice and strange and artful modulations in the scoring.”

There is no ample cantilena, but rather a capricious mood in the highly varied dynamic nuances of the Andantino. Neither does the amusing Tempo di minuetto erect any barriers against the growing number of music-lovers of the second half of the 18th century.

This was also the aim the new chamber music form practiced by Bach in his “Clavier Sonatas with a Violin and Violincello Accompaniment” of 1776 and 1777. Here the thorough bass is finally replaced by the keyboard part. The individually written melodic line is taken up by the treble in the keyboard. The violin and the violincello seem dispensable – but not for long.

In the hands of the Viennese classics and their piano and string trios equal rights would soon be restored to all of the instruments involved.

TRACK LISTING:

- 1-3: Sonata in A minor, Wq.156 (H.582) [10:17]

- 4-6: Sonata in F major, Wq.154 (H.576) [13:58]

- 7-9: Sonata in E minor, Wq.155 (H.577) [15:08]

- 10-12: Sonata in B-flat major, Wq.158 (H.584) [13:46]

- 13: Sonata in D minor, Wq.160 (H.590) [8:06]

FINAL THOUGHT:

It’s tough to be the son of a genius. I realize there many music scholars that would through C.P.E. Bach into the genius bucket – but I just don’t get it. C.P.E. Bach is kind of like Frank Sinatra, Jr. to me. Sure, he can carry a tune and even looks like his dad a bit, but when you watch him in some cheesy small room lounge in Las Vegas, you know you’re not seeing the real Ol’ Blue Eyes.

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company)

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company)