Ludwig Van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Ludwig Van Beethoven (1770-1827)

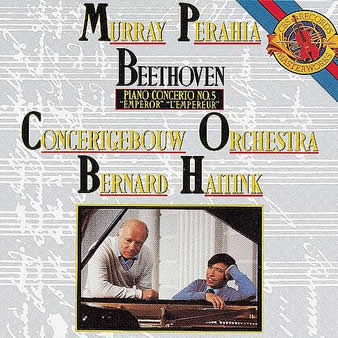

Concerto No. 5 for Piano & Orchestra in E-flat Major, Opus 73

Murray Perahia, Piano – The Concertgebouw Orchestra (Bernard Haitink, Conductor)

Recorded at the Concertgebouw, Amsterdam, 1986

ONE-SENTENCE REVIEW:

You know it – you love it – an excellent recording of a true masterwork.

ORIGINAL LINER NOTES (by Phillip Ramey):

Similar to his Seventh and Eighth Symphonies, Ludwig van Beethoven’s Fourth and Fifth Piano Concertos stand in considerable contrast to one another.

No. 4 (1804-06) is perhaps the most poetic and intimate of Beethoven’s concertos, a work in which lyricism is predominant; while No. 5 (1809) is animated by what might be termed the composer’s public-square manner, gesture rather than melody given pride of place.

E-flat major was the key favored by Beethoven (and others) for music of “heroic” cast. With the Fifth Concerto, one can go further and make a case for its being a “military” concerto.

Musicologist Alfred Einstein rightly described this score as the “apotheosis of the military concept” in Beethoven’s music, because of its martial rhythms, aggressive themes, motives of triumph and oft-pronunciatory nature.

Musicologist Alfred Einstein rightly described this score as the “apotheosis of the military concept” in Beethoven’s music, because of its martial rhythms, aggressive themes, motives of triumph and oft-pronunciatory nature.

According to Einstein, compositions in military style were familiar to Beethoven’s audiences: “They expected a first movement in four-four time of a ‘military’ character; and they reacted with unmixed pleasure when Beethoven not only fulfilled but surpassed their expectations.”

Certainly, there had never before been a piano concerto of such grand proportions or with such emphasis laid on brilliant pianistic effect for its own sake.

It has been theorized that between writing the Fourth and Fifth Concertos, Beethoven obtained a new and better piano, one that suggested the possibilities inherent in an improved instrument and provoked him to assign the piano an equal, even sovereign, role (as opposed to its more usual essentially ornamental role) when combining it with orchestra.

In any case, the E-flat Major Concerto’s extraordinary improvisatory cadezalike opening, with its decidedly magisterial tone, must have startled its first audiences, and the unprecedented length of the first movement (in Beethoven’s works, only the corresponding movement of the Eroica Symphony is longer) must have come as a surprise.

Beethoven wrote his Fifth Concerto during the invasion year 1809, when his native Vienna was besieged by Napoleon’s armies – a fact that surely dictated the music’s military atmosphere.

Occasionally, the composer took refuge from the bombardment in a basement room, where he covered his head with pillows to lessen the din. “The course of events has affected by body and soul,” he wrote “[and] life around me is wild and disturbing, nothing but drums, cannons, soldiers…”

Occasionally, the composer took refuge from the bombardment in a basement room, where he covered his head with pillows to lessen the din. “The course of events has affected by body and soul,” he wrote “[and] life around me is wild and disturbing, nothing but drums, cannons, soldiers…”

Beethoven developed a case of war fever, which expressed itself in outbursts of rage against Napoleon and the French.

During the occupation of the city, he was once observed in a coffeehouse shaking his fist at a French officer, shouting, “If I were a general and knew as much about strategy as I know about counterpoint, I would give you something to think about!”

The subtitle “Emperor” was appended not by Beethoven or its first publisher, but by tradition. It may have arisen from an incident that supposedly occurred at the Vienna premiere, on February 12, 1812, during the French occupation (Carl Czerny was soloist; there is no record that Beethoven himself ever played the work; by that time he grown too deaf to perform).

A French soldier in the audience, taken with the Concerto’s grandeur and imperiousness, reportedly cried, “C’est l’Empereur!” If true, the outburst cannot have pleased the staunchly republican composer, who in 1804 had angrily eradicated a dedication to Napoleon on the autograph score of his Eroica Symphony when Napoleon proclaimed himself Emperor of France.

The first performance of the E-flat Major Concerto evidently took place in Leipzig on November 28, 1811, at the seventh Gewandhaus Concert. The soloist was Johann Schneider, who may have been a Beethoven student, and the conductor was one Johann Phillip Christian Schultz.

The first performance of the E-flat Major Concerto evidently took place in Leipzig on November 28, 1811, at the seventh Gewandhaus Concert. The soloist was Johann Schneider, who may have been a Beethoven student, and the conductor was one Johann Phillip Christian Schultz.

The piece was enthusiastically received by the audience, and a January 1, 1812 noticed in the Allegemeine musikalische Zeitung described it as “undoubtedly one of the most original, imaginative, effective but also most difficult of all existing concertos.”

TRACK LISTING:

- 1: Allegro [20:30]

- 2: Adagio un poco moto [8:30]

- 3: Rondo: Allegro [9:43]

FINAL THOUGHT:

While the 20 minute opening movement is genius in a military-style bombastic kind of way, it’s really the 2nd movement that is the star here. From all I’ve heard of Beethoven’s work – it seems to me he really knew what he was doing.

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company)

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company)