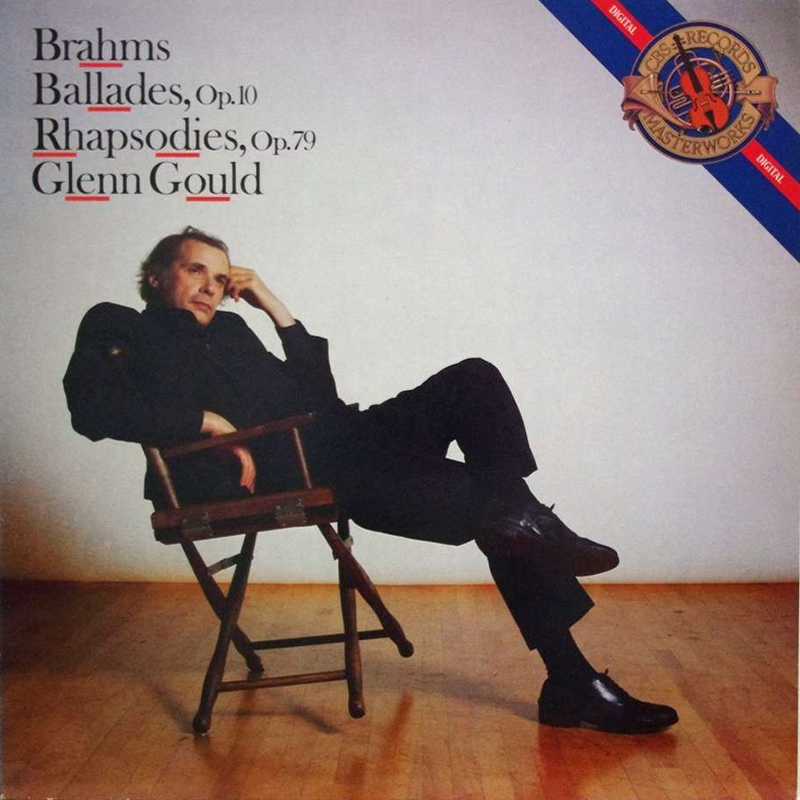

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897)

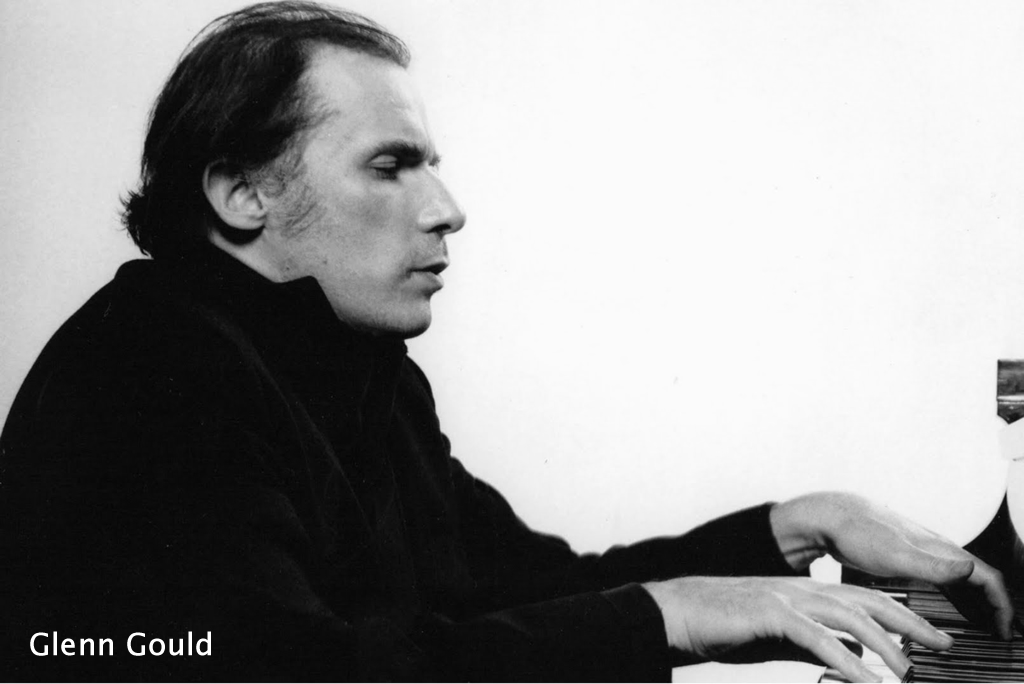

Glenn Gould, Piano

Recording Location: CBS Recording Studios, New York, NY, 1982

ONE-SENTENCE REVIEW:

There is nothing to review about Glenn Gould’s final piano recordings – just listen and love.

ORIGINAL LINER NOTES: (by Peter Eliot Stone)

The nineteenth century ballade took its earliest inspiration from literary sources – the ballads or narrative poems, usually German or English in origin, dealing with legendary, historical or often purely romantic characters and happenings.

Thus, ballades were early characterized by a programmatic content that could easily seize the imagination both of composer and listener alike. Works by some composers, such as Frederic Chopin, were even considered to parallel lines of poems – in Chopin’s case those by fellow-countryman Adam Mickiewicz.

Johannes Brahms, on the other hand, devoted his ballades, as a rule, to “absolute” music, and his Four Ballades, Op. 10 of 1854 contain only one “programmatic” piece – the first in D minor.

This Ballade musically embodies the famous Scottish ballad of patricide, Edward (“Why does your brand sae drop wi’ bluid, Edward, Edward?”), which Brahms knew in translation from Johann Gottfried Herder’s Stimmen der Volker and which he later set for alto and tenor (Op. 75, No. 1). Brahms climaxes this grim dialogue between mother and son with the Beethovenian fate motif that was to color many of his other works. When the opening theme returns, Brahms treats it in a surprisingly operatic fashion.

The second Ballade, in D major, departs from its lyrical mood with a dramatically contrasting middle section.

The elfin third Ballade, in B minor, labelled intermezzo and functioning in the set as a scherzo, likewise differentiates its middle section. Brahm’s interest in the inner voices of the fourth Ballade, in B major, reveals the influence of his friend Robert Schumann, but Brahm’s more classic reserve and his formal sophistication yield glimpses of the master’s mature style.

Brahms dedicated his Two Rhapsodies, Op. 79 (1879), to the charming and musical Elisabeth von Herzogenberg, originally entitling them “Capriccio (presto agitato)” and “Molto passianato.” For Brahms, the word capriccio did not seem to imply a light-hearted caprice (unless he used the titles ironically). Almost all of his caprices were gloomy, turbulent, and in the minor mode.

Regarding publication in 1880, Brahms suggested the title “Rhapsody” to Elisabeth. She answered: “You know I am almost most partial to the non-committal word Klavierstucke, just because it is non-committal: but probably that won’t do, in which case the name Rhapsodien is the best, I expect, although the clearly defined form of both pieces seems somewhat at variance with one’s conception of a rhapsody.”

Somewhat at variance, indeed!

Temperamentally “youthful” but compositionally mature, there is nothing improvisatory or irregular about these pieces. The first, in B minor, contains its agitation within a da capo form to which a coda has been added.

The second, in G minor, unleashes its passion through what for all intents and purposes is a sonata form. Yet the pieces do not resemble movements that might flow from the pen of the neo-classicist Brahms when he intended to write a sonata. Here, Brahms eschews the stable expository section for the instability of development right from the start.

In the first Rhapsody, the middle, bagpipe-like section, is based on a complete exposition of a “second theme” that had been arrived at prematurely and in the “wrong” key in the first section where it was then interrupted by a further intensive development of the first theme.

The G-minor Rhapsody opens with a true primary-group theme whose iambic rhythm, one of Brahm’s fingerprints, contrasts fittingly with the march-like secondary group theme. But the oppressive nature of this second Rhapsody continues to the bitter end, unlike the brief B-major close of the first Rhapsody which somewhat softens its turbulence.

TRACK LISTING:

- 1: Brahms Ballade, Op. 10, No.1 (D-Minor)

- 2: Brahms Ballade, Op. 10, No. 2 (D-Major)

- 3: Brahms Ballade, Op. 10, No. 3 (B-Minor)

- 4: Brahms Ballade, Op. 10, No. 4 (B-Major)

- 5: Brahms Rhapsody, Op. 79, No. 1 (B-Minor)

- 6: Brahms Rhapsody, Op. 79, No. 2 (G-Minor)

FINAL THOUGHT:

Below is a fascinating (audio) recording of the complete Brahms Ballades recording session from 1982. I didn’t listen to the complete 5 HOUR (!!) recording – but just so much great audio of Gould being Gould (so to speak). Enjoy!

[This recording receives the VERY RARE 88 out of 88 for the simple fact – it’s Glenn Gould’s last piano recording before his death. It may not deserve 88 out of 88 (from a review standpoint) but as a huge Gould fan, anything less would be silly.]

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company)

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company)