Schonberg Ensemble with Percussion Group The Hague and Netherlands Chamber Choir – Reinbert De Leeuw, Conductor

Recorded March 9, 1990 at Muziekcentrum Vrendenburg, Utrecht, The Netherlands

ONE-SENTENCE REVIEW:

If you like the sound of metal scraping against human bone, you’ll love De Tijd.

ORIGINAL LINER NOTES [EXCERPT] (by Elmer Schonberger):

‘mirando il punto a cui tutti li tempi son presenti’ (“… fixed on that point thy sight to which all times as present appertain”)

Dante, The Divine Comedy (Beatrice in ‘Paradisco’ 17th canto, line 17 – translation: J.W. Thomas)

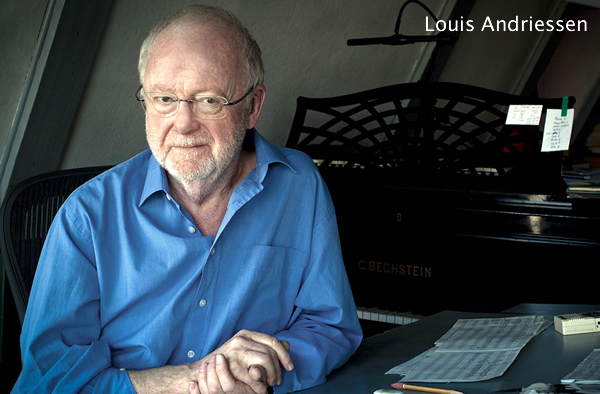

When Louis Andriessen was about two thirds of the way through composing his newest work De Tijd (Time), he played what he had written through, and he suddenly realized that if he managed to conclude it successfully he would have succeeded in doing something that he had wanted to achieve since 1972.

He remembered visiting a friend one evening ‘full of plans for big works – this was well before De Staat (The Republic) and very excitedly I shouted: “I want to compose a piece – nothing but terrifying blue columns. Very long. Bangs. Silences.”‘

Nine years later the work acquired its definitive form and title: De Tijd.

It was the third in a series of large instrumental-vocal pieces which began in 1976 with De Staat to a text by Plato, and continued three years later with Mausoleum to a text by Bakunin.

In De Tijd the ‘blue columns’ took the form of a drawn-out series of chords which supported a vocal cantus firmus; the ‘bangs’ constituted a second layer made up of strongly attacked chords which articulated the eternal present of the blue columns, imbuing the music with the present, past and future.

The ‘silences’ became bars of rest which functioned as interims – sometimes for all the musicians (as in the beginning of the ninth minute), at other times for the choir alone, such as when eternity (aeternitas) is mentioned for the first time – eternity of which it is ultimately said that ‘ever still standing it determines both past and future time, although itself neither past nor future.’

De Tijd ended up being a long pieces: 41 minutes in an unchanging tempo of 48.

In contrast with De Staat which was rooted in a musical vision, De Tijd is the musical image of what was originally a non-musical impression, once described by Andriessen as ‘a unique experience which gave me the feeling that time had ceased to exist, the feeling of an eternal moment.’

In contrast with De Staat which was rooted in a musical vision, De Tijd is the musical image of what was originally a non-musical impression, once described by Andriessen as ‘a unique experience which gave me the feeling that time had ceased to exist, the feeling of an eternal moment.’

The desire to transpose this experience into a work of ‘sustained exalted musical motionlessness’ spurred the composer on a quest into the scientific, historical and philosophical labyrinth of time, which began with Dijksterhuis’s classic De mechanisering van bet wereldbeeld (The Mechanization of the World Image) and Dante’s Divine Comedy, ending up two years later with Saint Augustine, and the same work by Dante which was to provide the superscription for the piece.

In the meantime, the composer’s journey extended from Florence – where he was researching into a particular philosopher who was a contemporary of Dante’s – to Tunisia where in December 1980, more or less by coincidence, he wrote the last bars of the short score of De Tijd hardly sixty kilometers from Saint Augustine’s birthplace.

‘Quid est ergo tempus?’ is the famous question Saint Augustine asked himself: ‘What, then is time? I know well enough what it is, provided that nobody asks me; but if I am asked what it is and try to explain, I am baffled.’

Entirely at odds with his original intentions, Andriessen ended up writing music that measure time rather than expression the ‘eternal moment,’ and in contrast with this he used a text with a metaphysical import.

TRACK LISTING:

- 1 – De Tijd [42:56]

FINAL THOUGHT:

This is not cocktail party music. And really terrible for some sort of outdoor picnic or wedding reception. This is first rate haunted house music or perfect to set the mood at a creepy art installation. The listener may very well need a little bit of early Mozart to get the pounding, disturbing, dissonant clock strikes out of your head.

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company)

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company)