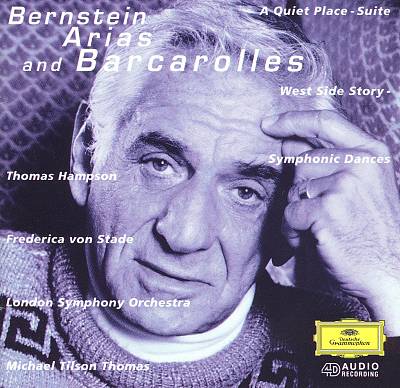

West Side Story: Symphonic Dances

London Symphony Orchestra, Michael Tilson Thomas – Conductor

Recorded September 1993 – London, Henry Wood Hall

ONE-SENTENCE REVIEW:

I was excited to listen to this disc again – such rhythmic bravura and musical surprises from Mr. Bernstein!

ORIGINAL LINER NOTES (by MIchael Barrett):

ARIAS AND BARCAROLLES (1988)

Two of Leonard Bernstein’s last compositions, A Quiet Place (1983) and Arias and Barcarolles (1988) share the same subject: the modern American family.

Arias and Barcarolles, a concert work, gives us fleeting glimpses into a marriage (there are two duets for couples, a wedding scene and meditations on birth and death).

The opera A Quiet Place, written in collaboration with the librettist Stephen Wadsworth is the story of a broken family thrust back together at a funeral (Act 1), showing, in flashbacks, their turbulent history (Act II, which incorporates Trouble in Tahiti, Bernstein’s one-act opera from 1951), and, after the funeral, their eventual reconciliation (Act III).

But the two works have more than a theme in common.

As Michael Tilson Thomas has put it: “Quiet Place and Arias and Barcarolles both show LB as a masterful musical conjurer. He is so amazing in transforming tone rows from angry ostinatos to scat riffs, bluesy ballads or Mahlerian adagios. The music is so clever, yet engaging and satisfying to follow. He was so happy that in these… works he had really conquered serial writing and that he achieved it, not by excruciating study, but by applying his brilliant sense of gamesmanship. If Lenny had wanted to write ‘brainy,’ really difficult music he certainly could have. With his mastery of mental jotto and acrostics, he could have out-puzzled us all. But the essence of music and life for him was communication. His work poses questions and conundrums but also offers solutions.”

As Michael Tilson Thomas has put it: “Quiet Place and Arias and Barcarolles both show LB as a masterful musical conjurer. He is so amazing in transforming tone rows from angry ostinatos to scat riffs, bluesy ballads or Mahlerian adagios. The music is so clever, yet engaging and satisfying to follow. He was so happy that in these… works he had really conquered serial writing and that he achieved it, not by excruciating study, but by applying his brilliant sense of gamesmanship. If Lenny had wanted to write ‘brainy,’ really difficult music he certainly could have. With his mastery of mental jotto and acrostics, he could have out-puzzled us all. But the essence of music and life for him was communication. His work poses questions and conundrums but also offers solutions.”

After playing Mozart and Gershwin at the White House in 1960, Bernstein experienced a somewhat awkward moment, President Eisenhower greeted him and said, “You know, I liked that last piece you placed; it’s got a theme. I like music with a theme, not all those arias and barcarolles.”

According to Eisenhower’s definition, Arias and Barcarolles at first would seem to be music without a theme; the musical elements are disparate and eclectic: twelve-tone writing, rhythmic improvisation, late romanticism, scat-singing and pure Coplandesque Americana.

There is, however, a theme running through the texts, which is revealed in the opening lines of the “Prelude”: “I love you, it’s easy to say it, and so easy to mean it, too.” We have entered the private and sometimes dark thoughts of a couple, and are off on a musical exploration of different aspects of love.

The “Prelude”‘s accompaniment, spiky, discordant and rhythmic, is periodically interrupted by the impassive vocal line, which seems oblivious to the musical storm brewing behind it.

This idea of turmoil masked by calm is continued in the lyrical “Love Duet,” where both characters sing a random list of everyday questions while narrowly avoiding the deeper conflicts lurking beneath their ironic detachment.

This idea of turmoil masked by calm is continued in the lyrical “Love Duet,” where both characters sing a random list of everyday questions while narrowly avoiding the deeper conflicts lurking beneath their ironic detachment.

Over constant, machine-like eighth-notes (quavers) in the orchestra – the piece is in 10/8 meter – the couple is singing about the song they are singing (about their relationship!). It defies their categorization, like the music of Arias and Barcarolles itself: (Is it) “minimal music or classical or popular song? All of them wrong.”

“Little Smary” is a bedtime story the composer remembered hearing repeatedly as a child, told by his mother, Jennie Bernstein, who is credited with authorship of the text. The musical setting follows a double course, alternating the mother’s bright, animated tone with the profound emotions experienced by the child listening. There is a despairing Berg-like interlude at Smary’s loss of her little “wuddit” (rabbit), and a brilliant Straussian flourish at her triumphant recovery of it at the end of the song.

After this brief excursion into the world of children, “The Love of My Life” takes us back to the realm of adult reflection through a long, improvistory twelve-tone orchestral introduction. (The notes are indicated, but not the precise rhythms). The tone row alternates mercurially with tonal sections in a variety of moods, including a few measures of hard-driving blues. The song is edgy, obsessive, questioning and, at the end, ironic, subtly quoting the beginning of Tristan und Isolde at the words, “So that was it, huh?”

“Greeting” was written in 1955 after the birth of the composer’s son Alexander, and then revised in 1988. In its rapt, ethereal atmosphere it hovers above the key of A major without ever actually alighting on an A major triad, and ends on the dominant, E. The repose in this song is the eye of the hurricane of emotion elsewhere in the work.

“Greeting” was written in 1955 after the birth of the composer’s son Alexander, and then revised in 1988. In its rapt, ethereal atmosphere it hovers above the key of A major without ever actually alighting on an A major triad, and ends on the dominant, E. The repose in this song is the eye of the hurricane of emotion elsewhere in the work.

“Oif Mayn Khas’neh” (“At My Wedding”), the setting of a Yiddish poem by Yankev-Yitskhok Segal, is a surrealistic reminiscence of a wedding. Like “The Love of My Life,” it uses a twelve-tone row as a recurring motif, while the music courses through many different tonalities. The song illustrates an essential theme of Arias and Barcarolles: passion can inspire love, but it can also unleash mayhem. At the mid-point in the song, there is a cantorial cadenza. The music then builds from a quiet, slow recapitulation of the opening, accelerating in tempo to a frenzied climax at the end of the song.

“Mr. and Mrs. Webb Say Goodnight” is an affectionate portrait of Charles Webb (Dean of the Indiana School of Music), his wife Kenda, and their sons Malcolm and Kent (in the original version, their parts are taken by the pianists; here they are performed from the orchestra).

In this little domestic drama, played out at four in the morning, the two rambunctious children are head singing together. Kenda, having scolded them into temporary silence, can’t sleep and takes the opportunity to throw a tantrum. Charles calms her with a romantic memory, they say their prayers one last time, and fall asleep as the children are heard quietly scat-singing once more.

A truculent march begins the piece, which continues in a succession of popular music styles — cool jazz for the children, a virtuosic musical theatre-style patter for Mrs. Webb’s tirade and a suggestion of swingtime for Mr. Webb’s reminiscences.

A truculent march begins the piece, which continues in a succession of popular music styles — cool jazz for the children, a virtuosic musical theatre-style patter for Mrs. Webb’s tirade and a suggestion of swingtime for Mr. Webb’s reminiscences.

The “Nachspiel” (Postlude) is a slow waltz, with the two singers humming a descant. Headed “in memoriam,” this final song maintains an inward, elegiac tone, never rising above a hush. The piano version has also been published in a collection of “Thirteen Anniversaries.”

Arias and Barcarolles was first performed in New York in May 1988 in a version for four singers (Joyce Castle, Louise Edeiken, John Brandstetter, Mordechai Kaston) and piano duet (the composer and Michael Tilson Thomas); the version with two voices had its premiere in Tel Aviv in April 1989 (Amalia Ishak, Raphael Frieder, Irit Rub-Levy, Ariel Cohen) and its first New York performance in September 1989 (Judy Kaye, William Sharp, Michael Barrett, Steven Blier).

An arrangement by Bright Sheng for strings and percussion was first performed in New York in September 1989 (Susan Graham, Kurt Ollimann, the New York Chamber Symphony of the 92nd St. Y conducted by Gerard Schwarz).

The orchestration by Bruce Coughlin was given its first performance in London in September 1993, with the conductor, orchestra and soloists of the present recording.

After four productions and one major revision, A Quiet Place has still to find a foothold in the repertoire, yet it contains music which is arguably among the most powerful, affecting and lyrical Bernstein ever wrote.

Much of this has been included in the suite, which was compiled by Michael Tilson Thomas, myself and Sid Ramin, who also provided the additional orchestrations. The first performance was given in September 1991 by the London Symphony Orchestra conducted by Michael Tilson Thomas.

The suite begins with the Prologue, the musicalization of a violent car accident, accompanied in the opera by the comments of witnesses and onlookers (the chorus); in the suite these are exclaimed by an array of percussion instruments following the contour and rhythm of the original Spechstimme choral parts.

A brass chorale emerges, growing phrase by phrase to reach a dramatic climax. In the opera, it is sung to words from Dinah’s final diary entry, “Give all for love, for love is strong as death.” It is she who has been killed in the car accident, and it is her funeral with which the opera begins. Attending are her husband Sam, their grown children, who arrive late, and family friends.

Silent and aloof through most of Act 1, Sam finally, in an operatic tour de force, gives vent to his rage, guilt and frustration toward himself, his children and his deceased wife (Sam’s Aria). In the suite, Sam’s baritone is given to the trombone, propelled by brilliant, metrically shifting orchestral outbursts.

The response to Sam’s fierce Aria is the beautiful Trio, sung by his and Dinah’s daughter Dede, their son Junior, and Dede’s husband, Francois. They recall heartfelt letters they wrote as children to their fathers. Here the vocal lines of Dede (soprano), Junior (baritone) and Francois (tenor) are taken by solo viola, bassoon and english horn respectively.

The Jazz Trio (“Mornin’ Sun” ) from Trouble in Tahiti depicts the troubled marriage of Sam and Dinah 30 years earlier. The words describe, somewhat ironically, the bliss of upper-middle class suburban life in 1950s America. The light, nightclub-combo scoring of the original has been re-worked in the suite into a Big Band number, giving it symphonic weight.

The opening chorale from the Prologue returns, this time quietly and without a climax, punctuated only by fragments of the jazz clarinet tone-row from Trouble in Tahiti.

The suite ends with the Postlude to Act 1. Junior is left alone onstage with his mother’s coffin, after one of his aggressive psychotic episodes has effectively cleared the funeral parlor of family and friends. In this wordless scene, in which he becomes aware of his disarray, the music describes his remorse, tender memories of his mother, and anguish of his grief.

WEST SIDE STORY: SYMPHONIC DANCES

WEST SIDE STORY: SYMPHONIC DANCES

Some commentators have gone so far as to call West Side Story the great American opera that composers have supposedly been trying to write for decades.

Bernstein himself, however, reminded us that West Side Story is not an opera: the denouement is spoken, not sung. And so the work remains a child of the Broadway stage – where it opened in September 1957 and ran for nearly two years – albeit one of its most complex and sophisticated children.

It is a testimony to Bernstein’s gifts and versatility that material from a successful Broadway musical could be turned into a symphonic score which has found a secure place in the standard orchestral repertoire.

In collaboration with the choreographer and director Jerome Robbins, Bernstein created a theatrical world where dance is on an expressive par with song and dialogue. Much of West Side Story is told through dance, and the choreography generates the essential energy of the action; writing dance music allowed Bernstein to deploy the full range of his compositional powers.

The Symphonic Dances (1960) extracted from the complete work are arranged according to an organic plan rather than in dramatic sequence. In their orchestration Bernstein had assistance from his lifelong friend, Sid Ramin, and Irwin Kostal, who together had recently revised the scoring of West Side Story for the screen version.

The first performance of the Symphonic Dances was conducted by Lukas Foss with the New York Philharmonic in February 1961.

Bernstein’s amanuensis Jack Gottlieb has outlined the action of the principal sections of the Symphonic Dances as follows:

- Prologue: The growing rivalry between two teenage gangs, the Jets and Sharks.

- Somewhere: In a visionary dance sequence, the two gangs are united in friendship.

- Scherzo: In the same dream, they break through the city walls, and suddenly find themselves in a world of space, air and sun.

- Mambo: Reality again; competitive dance between two gangs.

- Cha-Cha: The star-crossed lovers see each other for the first time and dance together.

- Meeting Scene: Music accompanies their first spoken words.

- “Cool” Fugue: An elaborate dance sequence in which the Jets practice controlling their hostility.

- Rumble: Climactic gang battle during which the two gang leaders are killed.

- Finale: Love music developing into a procession, which recalls, in tragic reality, the vision of “Somewhere.”

TRACK LISTING:

- 1-8: Arias and Barcarolles (1988) [33:45]

- 9-14: A Quiet Place: Suite (1983) [22:07]

- 15-23: West Side Story: Symphonic Dances (1957) [22:10]

FINAL THOUGHT:

After those notes up there, I doubt anyone has made it to the bottom of the blog. But if you did, the video above is a real treat (not from the disc featured – but the “Mambo” from West Side Story is in the Symphonic Dances. This video, conducted by the great Gustavo Dudamel is a real joy!

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company)

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company)