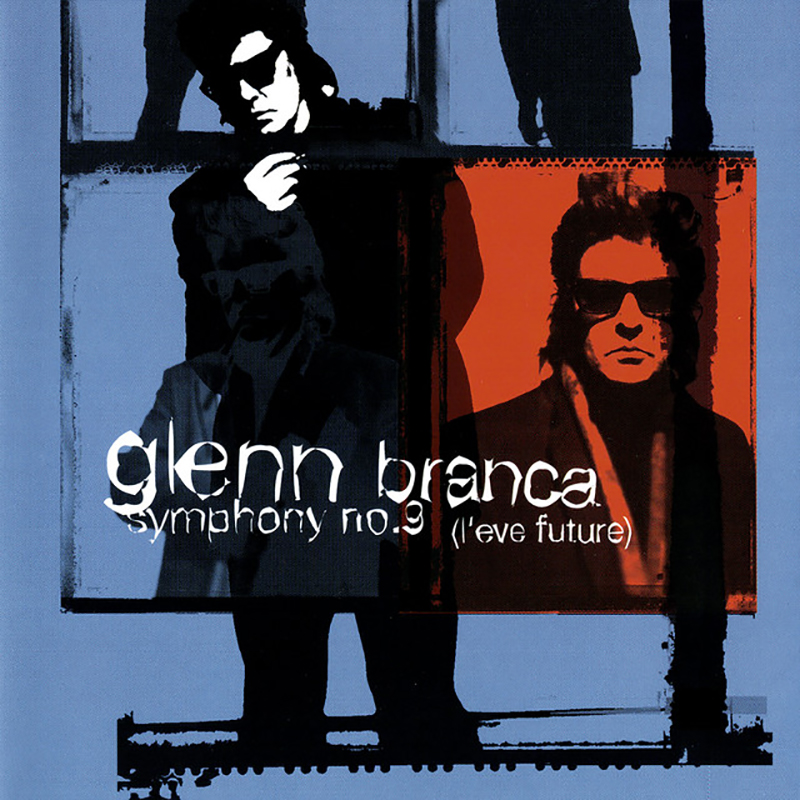

Glenn Branca (1948-2018)

Symphony No. 9 (L’eve Future)

Free Form

Performed by: The Polish Radio National Symphony Orchestra & Camerata Silesia Singers Ensemble

Conducted by: Christian Von Borries

Recorded at the Concert Hall of the Polish National Symphony Orchestra in Katowice, Poland – October 1994.

Glenn Branca’s Symphony No. 9 was commissioned by Freunde Guter Music Berlin for their 10th anniversary. The first performance took place during the U.S. Arts Festival Berlin on July 13th, 1993, at the Parochialkirche by the Moravian Philharmonic conducted by Christian von Borries.

ONE-SENTENCE REVIEW:

Based on the notes entered below, I was expected a bat-shit crazy cacophony of crap – but when I listened to it for the first time in years, it comes across as a thoughtful (or thoughtless) droning of interconnected ideas.

A bullet-hole big as a harvest moon, tattered open, torn & bleeding in a royal blue metallic scrim of a sky limned lattice-like intricate nerve-grid. An unblinking iris, constant as consciousness, peers through the opening, silently rotating 360 degrees with imperceptible rhythmic precision. A distant hum undulating from distant horizons. The fibrillating murmur of ghosts and angels massed together in the shifting mist.

The apocalypse is over. This is what comes after.

ORIGINAL LINER NOTES – Tim Holmes, New York City, March 1995

L’eve Future. As it turns out, a pun.

At first, it intimates the precipice before tomorrow, a shadowy glimpse behind the veil, the night before the morning after. Read aloud, phonetically, it suggests the question: if, “in the late 20th century the im-possible becomes possible,” then we could we leave the future & go somewhere else instead?

All corners of the culture, from the pundits of Wired to the Speaker of the House, are screeching evangelist visions of a neo-biological high-tech global utopian hive. The planet itself is already shrouded in a crypto-neurological myelin sheath, the better to transmit pornography & “information” from PC to PC over the phone lines. The only thing standing between right-this second and no-reason -to-ever-leave-the-house is bandwidth.

[Before this rant spirals any further, the following disclaimer – 1): Glenn Branca, an early and rabidly enthusiastic proponent of cyberpunk, cannot, by any stretch, be called tech-nophobic (he uses a computer as a compositional tool and has been interviewed by Mondo 2000).]

In order to make a tag like “genius” stick, the following must be in place: 1) you gotta invent (or “discover”) something; 2) the influence of the work must extend beyond genre and / or field of endeavor (i.e., you don’t have to be a scientist to be affected by Thomas Edison, you don’t even have to know who he was; 3) genius affects history & is (preferably) unpredictable.

Glenn Branca is arguably, if not irrefutably, the first human since Jimi Hendrix (who I’m still not convinced was not some kind of extraterrestrial) to do something radically new with electric guitar.

Uncovering the harmonic series woven into Nature, he created tuning systems & built instruments to amplify these complex mathematical truths, assembled electric guitar orchestras, structured the pieces in classical symphonic forms, & troweled on the overtones so loud & thick & dense that the roaring cascades of pure sound whorled and whoomed with mushroom cloud wind-tunnel ferocity, every molecule saturated zig-zag harmonics colliding pinwheels like atom-smashing acceleration chamber in every cilia & it felt like the DNA double helixes were being ripped apart, nerve cells erupting in ecstasis des and don’t think for two seconds that these all-too-rare performances didn’t leave an indelible imprint on the future of electric music & apprentices in acoustic phenomena…

And now, I’m gonna roller blade out on a big limb & announce my belief that Symphony No. 9 is the most drastic work in the Branca canon.

For it is here, in the 9th (traditionally, from Beethoven to Mahler, the most mystical of symphonic #’s, the one that foretells death & the afterlife: Glenn’s already written, recorded, & performed his 10th so he’s beaten the jinx & broken another tradition) that Glenn Branca, of all composers, breaks Josef Haydn’s “Sonata For Orchestra” routine (even Branca’s guitar symphonies have “movements”), collapsing the original symphonic functions of prelude, interlude, and postlude into an undulating extended moment (a split-second in eternity unfolding over the course of approximately 50 minutes) of impossible contradictions at once expanding & contracting, ascending & descending, accelerating & decelerating, intervallic contrapuntal modules overlapping & splitting with the organic elegance & inevitability of mitosis on an intergalactic scale, sublime, enigmatic, and divine.

In 1983, I was playing guitar with Glenn on a chaotic North American Club & Arthouse Tour. Right before we went on in Boston, a woman in her sixties (whose name I couldn’t remember if you offered me a thousands dollars, although for that kind of money I’d like & make something up) came backstage & introduced herself as an old college chum of my mother’s.

Now this woman had no idea who Glenn Branca was & she certainly wasn’t a rock & roll person & basically she was somebody who knew me from the family Xmas cards, & she was a spy sent by mom to report back whether I was getting enough to eat & that kind of thing. “I can only stay a minute,” she explained because her husband was waiting outside in the car & they were going to dinner, but she was gonna see what we all looked like on-stage.

So, the Glenn Branca Ensemble came out & performed “Indeterminate Activity of Resultant Masses,” the piece that had John Cage frothing to journalists about what horrible fascist music Glenn was writing & if this was the future, then he sure as hell didn’t want to live there.

To make a long story interminable, we finished the 50 minute piece that begins with a series of guitar overtones & builds to insane crescendos of skull-melting bone-shattering volume & when I came off-stage, the friend of my mother’s still there with her mouth hanging open & this look of post-orgiastic religious after glow in her eyes & I said, “Isn’t your husband outside?” & this look of horror broke through the trance & she sputtered “Omigod, that’s right!” & ran out the door.

I break into this anecdote to make a couple of points. It was then that I realized that people who knew how to listen to music were perfectly capable of “getting” what Glenn was up to, & I also think that what is so heartbreakingly subtle in “L’eve Future” is a quality underlying every piece he’s ever written (at least every piece I’ve ever heard that’s he’s written).

After a lot of Glenn’s performances, people report various kinds of Gnostic sonic visitations, phantom sounds that mysteriously appear in the music chimes, keyboards, horns, choral effects of vast proportions.

In his 9th Symphony, Glenn Branca has literally scored those voices: the piece has, in some sense, hundreds of movements playing off one another, the way the harmonics used to, to create a totality of monumental proportions.

Listening to a tape of “L’eve Future” in my office, a co-worker (who happens to be familiar with Glenn’s work & reputation as a gris eminence to a whole generation of rock-kids) said the music was both “sad” and “scary.” I maintained that Symphony No. 9 was, in a way, (disclaimer 2) what Glenn’s music had always been underneath it all.

Music, unlike any other human endeavor, creates its own temporality. Unlike life, its transience is internal, an illusion, generated by the duration the listener’s experience. Unlike language, music can only exist in an eternal present tense: the verb is the prism of language, there are no verbs in music.

In Glenn Branca’s Symphony No. 9, the uncanny simultaneous tension & repose of the music blending wordless choral lines and the instrumental arrangements suggest, without ever stating, openings and closings all at once.

I once suggested to Glenn – a guy who once told me, during a five-and-a-half-hour discussion of the True Construct of Reality, that he really liked reading Nietzsche because he’d finally found someone who was maybe smarter than he was – (Disclaimer 3) that God wrote the music (the Amadeus theory) which, of course, led to an extremely convoluted (on both parts) theological debate, & if “God” bugs you just substitute Nature, although I find it hard to completely swallow the idea that a True Atheist would write a prayer as profound & detailed & rigorous & passionate & beautiful as “L’eve Future,” which sounds like, among a thousand other things that’ve never been written, as elegy for the 21st Century on the occasion of its passing.

“L’eve Future” literally occurs somewhere outside time, a place beyond the eternal. And, when its over, without warning, it simply stops…

Christian von Borries was solo flute at the Opernhaus Zurich when he decided to start conducting. He studied with Gerhard Samuel in Cincinnati and Nicolaus Harnoncourt in Salzburg: he also consulted Carlos Kleiber. Since then, Christian von Borries is working free lance. He conducted first and created performances of Bruckner, Mahler, Schoenberg, and Berg. He is also active with conceptual concert series and radio happenings.

TRACK LISTING:

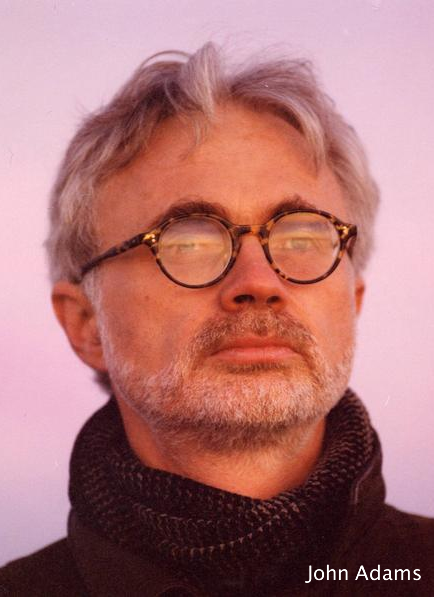

Glenn Branca

- Symphony No. 9 (L’eve Future) – 47:15

- Freeform – 11:43

Shockingly, I could not find a performance of Glenn Branca’s Symphony No. 9 on the internet… at all… anywhere. So here is an interesting interview he gave a few years before his death – and I threw in a performance of the insane Symphony No. 16.

FINAL THOUGHT:

I mean, not much more to add – other than, what the hell are those liner notes? I’m not sure I understand any of it other than Glenn Branca seemed to believe he was the smartest person every – except for Nietzsche – which can be interpreted as… disturbing.

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company