BBC Symphony Orchestra, Andrew Davis – Conductor

Recorded live at Hitomi Kinen Kodo, Tokyo, on May 28, 1993 (BBC Music)

ONE-SENTENCE REVIEW:

What to say about this version of Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique that I didn’t say about the last one… oh, yeah… this one is better!

ORIGINAL LINER NOTES (by Robert Cowan):

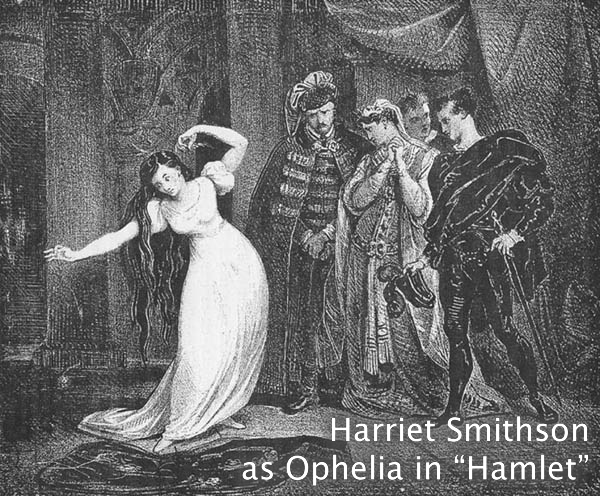

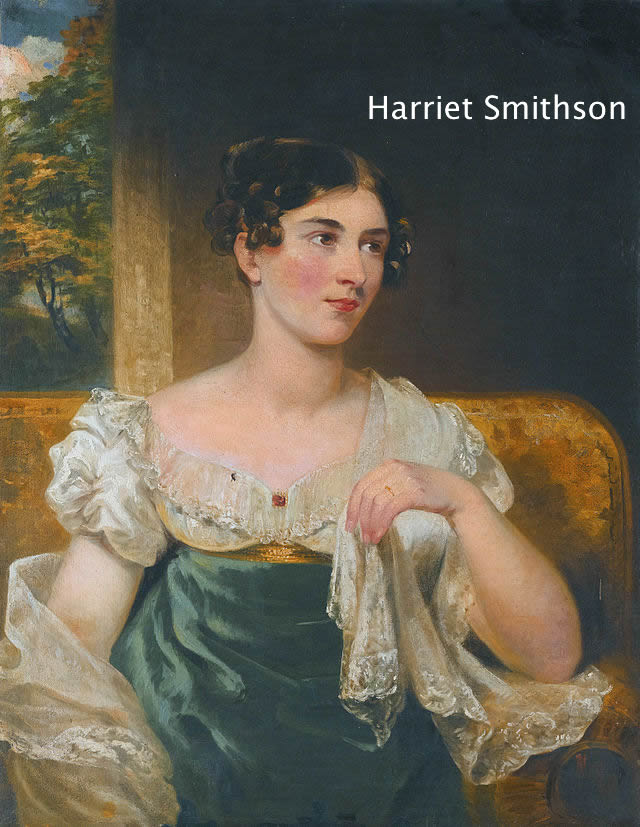

Berlioz’s semi-autobiographical Symphonie Fantastique grew out of his burning infatuation for the Irish actress Harriet Smithson. He had seen Smithson play Ophelia in 1827, and his Symphonie was completed three years later.

Berlioz’s semi-autobiographical Symphonie Fantastique grew out of his burning infatuation for the Irish actress Harriet Smithson. He had seen Smithson play Ophelia in 1827, and his Symphonie was completed three years later.

Berlioz himself stated in a programme note that it was his intention in the piece to ‘treat various states in the life of an artist, insofar as they have musical quality.’

It was the first major orchestral work to follow a detailed programme, and broke new ground by introducing the concept of an idee fixe, or recurring ‘motif,’ in this instance representing Harriet Smithson.

Wagner was to learn a great deal from Berlioz’s innovation and indeed his own ‘leitmotif’ is inconceivable without Berlioz’s inspired prompting.

A further revolutionary aspect of the symphony is its five-tier structure.

Each movement has a subtitle that refers to a specific aspect of the programme: the first, ‘Daydreams – Passions,’ reflects wavering joys, fears and frustrations in the face of amatory obsession; the second, ‘A Ball,’ recalls happier times, but a chance encounter with the beloved deflates its high spirits; ‘In the Meadows’ opens to the pastoral piping of two shepherds and ends with distant thunder; the ‘March to the Scaffold’ reports the artist’s attempted suicide, his dreams of killing the woman he loved and his death by the guillotine; and ‘Sabbath Night’s Dream’ finds him among spirits, sorcerers and monster, preparing for his own funeral.

Each movement has a subtitle that refers to a specific aspect of the programme: the first, ‘Daydreams – Passions,’ reflects wavering joys, fears and frustrations in the face of amatory obsession; the second, ‘A Ball,’ recalls happier times, but a chance encounter with the beloved deflates its high spirits; ‘In the Meadows’ opens to the pastoral piping of two shepherds and ends with distant thunder; the ‘March to the Scaffold’ reports the artist’s attempted suicide, his dreams of killing the woman he loved and his death by the guillotine; and ‘Sabbath Night’s Dream’ finds him among spirits, sorcerers and monster, preparing for his own funeral.

Berlioz’s original scoring included an ophicleide (an obsolete low brass instrument, commonly replaced nowadays by the tuba), bells (doubled, originally, by six pianos), an E-flat clarinet, and a pair of cornets, although the cornets aren’t always used in modern-day performances.

The Symphonie Fantastique, or five ‘episodes in the life of an artist,’ was premiered at the Paris Conservatoire on December 5, 1830, under the direction of Francois-Antoine Habeneck.

Another leading pioneer of musical Romanticism, Franz Liszt, was in the audience, and within three years he had undertaken the gargantuan task of transcribing the entire symphony for piano solo.

TRACK LISTING:

- 1: Daydreams – Passions [15:05]

- 2: A Ball [6:13]

- 3: In the Meadows [15:52]

- 4: March to the Scaffold [6:29]

- 5: Sabbath Night’s Dream [9:57]

—————————————-

This whole bit about Berlioz writing this piece for some Irish actress chick was news to me. And they ended up marrying in 1833 (the liner notes should have mentioned that!). The marriage fell apart by 1840 after Berlioz started having an affair. Harriet Smithson moved out, suffered a form of paralysis that left her barely able to speak and died in 1854. Just another tragic tale from the Romantic era.

(I put pictures of Harriet Smithson in throughout the notes because she is more interesting looking that Hector Berlioz – sort of like Kristen Wiig in this one.)

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company)

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company)