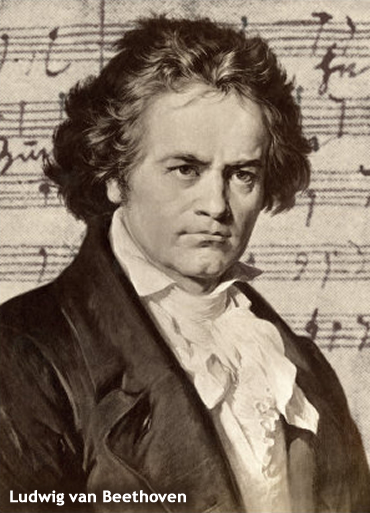

Ludwig Van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Ludwig Van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Symphony No. 9 in D Minor, Opus 125 – “Choral”

Philharmonia Orchestra & Chorus (Otto Klemperer, conductor)

Recorded October & November, 1957 – Kingsway Hall, London

ONE-SENTENCE REVIEW:

So, apparently, Otto Klemperer knows a little something about Beethoven – and he really knows how to conduct the Hell out the Ninth Symphony (though I wonder if this is the slowest recording of it ever made – a whopping 72 minutes!).

ORIGINAL LINER NOTES:

KLEMPERER AND BEETHOVEN (written by John Lucas – 1998):

Although Otto Klemperer had conducted complete cycles of Beethoven’s symphonies in the United States, Italy, France and the Netherlands, it was not until the late autumn of 1957 that he had an opportunity to conduct all nine symphonies in London, in a series of 10 concerts with the Philharmonia Orchestra.

The piano concertos were also included, with Claudio Arrau as soloist.

Herbert von Karajan came to London especially to hear the Eroica. After the performance he went to see Klemperer in the conductor’s room at the Royal Festival Hall. ‘I have come only to thank you,’ said Karajan, ‘and to say that I hope I shall live to conduct the Funeral March as well as you have done it. Good night.’

Walter Legge, founder of the Philharmonia and Klemperer’s record producer at EMI, was cock-a-hoop about the success of the concerts with both audience and critics.

Walter Legge, founder of the Philharmonia and Klemperer’s record producer at EMI, was cock-a-hoop about the success of the concerts with both audience and critics.

He reported to Angel Records, the company’s subsidiary in the United States: ‘Klemperer goes from strength to strength. When we have completed the Ninth I shall have given you a Beethoven cycle on records that will be prized as long as records are collected.’

The cycle at the Festival Hall concluded with two performances of the Ninth Symphony, in which the Philharmonia Chorus, trained by Wilhelm Pitz, the Bayreuth chorus-master, made its debut.

The finale, reported The Times on November 13, ‘exceeded in grandeur and brilliance and human exhilaration all that the foregoing movements had implied.’

Six of the Beethoven symphonies in the Klemperer Legacy series were recorded by EMI at the time of the 1957 cycles: the Second and Sixth Symphonies during the week before it began, the First, Fourth, Eighth and Ninth while it was still in progress. The Seventh comes from 1955, the Eroica and Fifth from 1959.

SYMPHONY NO. 9 ‘CHORAL’ etc. (written by Robin Golding – 1998):

In the summer of 1817, nearly three years after the completion of his Eighth Symphony, Beethoven was approached by the Philharmonic Society in London (founded in 1813) with a request for two new symphonies, to be performed during the 1818 season.

The invitation was conveyed to him by his former pupil, secretary and copyist, Ferdinand Ries, who was then living in London, and Beethoven wrote to Ries on July 9th, promising that they would be ready by January 1818 and that he would himself bring them to London.

The invitation was conveyed to him by his former pupil, secretary and copyist, Ferdinand Ries, who was then living in London, and Beethoven wrote to Ries on July 9th, promising that they would be ready by January 1818 and that he would himself bring them to London.

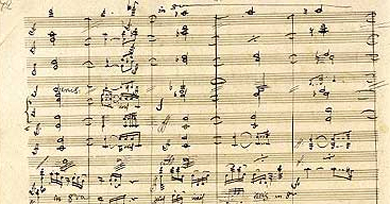

But he would not accept the terms offered by the Society, and the project came to nothing, although he did make substantial sketches for the first two movements of what was to become the Ninth Symphony.

It was not until the autumn of 1822, with the bulk of the Missa Solemnis behind him, that he turned his attention to the symphony in earnest, and most of the must was written between then and the end of 1824.

The idea of setting Schiller’s ode An die Freude (‘To Joy’), of 1785, had occurred to him at least as early as 1793, but it was not until 1822 that it became associated in his mind with the symphony.

He originally intended to end No. 9 with an instrumental finale (he later used the music he designed for this movement in the String Quartet in A minor, Opus 132), and even after the first performance of the symphony expressed some doubt as to whether he had made the right decision.

In November 1822 the Philharmonic Society offered Beethoven fifty pounds for eighteen months’ exclusive possession of a new symphony, and the composer accepted, though grudgingly.

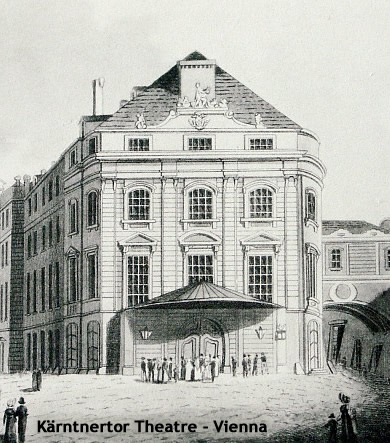

In April 1824 (having received his fifty pounds) he sent the Society a manuscript copy of the score, with a dedication, in his own hand, ‘For the Philharmonic Society in London,’ but he evidently thought that ‘exclusive possession’ only referred to England, since he allowed the symphony to be performed on May 7th, 1824 at the Karntnerthor-Theater in Vienna.

The conductor was Michael Umlauf, and at the end one of the soloists had to turn Beethoven round to face the audience because he could not hear the tumultuous applause.

The score and parts were published in August 1826 by Schott in Mainz, with a dedication to King Friedrich Wilhelm III of Prussia.

The first English performance was given on March 21st, 1825 at the New Argyll Rooms in London (with the last movement sung in Italian!) under Sir George Smart, a founder-member of the Philharmonic Society.

The three purely instrumental movements of the Ninth Symphony are on a scale whose only parallel among Beethoven’s earlier symphonies is offered by No. 3 (the Eroica) of 1802-4: an immensely grand, dignified and impassioned sonata form Allegro; possibly the greatest scherzo ever written, with a crucial part for the timpani, tuned in octaves, as in the finale of No. 8; and an expansive theme and variations interspersed with episodes, in B flat major.

The colossal finale, set to about a third of Schiller’s poem celebrating the brotherhood of Man, and for four (SATB) soloists and chorus in addition to the orchestra, is itself as long as, and fuller of incident than, most classical symphonies.

The ballet Die Geschopfe des Prometheus (‘The Creatures of Prometheus’) to a (lost) scenario by Salvatore Vigano, was produced at the Hofburgtheater in Vienna on March 28th, 1801, with music composed by Beethoven during the preceding year and consisting of an introduction and sixteen numbers, prefaced by the exuberant Overture recorded here.

TRACK LISTING – BEETHOVEN SYMPHONY NO. 9 ‘CHORAL’

- 1: Allegro ma non troppo un poco maestoso [17:03]

- 2: Molto vivace – Presto [15:38]

- 3: Adagio molto e cantabile [15:02]

- 4: Presto [24:27]

- 5: Prometheus Overture, Opus 43 [5:35]

FINAL THOUGHT:

So the Philharmonic Society of London got the exclusive rights to Beethoven’s 9th Symphony for 50 Pounds? Best 50 Pounds ever spent! (Though, I know, in today’s dollars that’s not too terrible – but still!) And it’s definitely a better rate than what Mozart was getting.)

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company)

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company)