Ludwig Van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Ludwig Van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Sonata for Piano No. 30 in E Major, Opus 109

Sonata for Piano No. 31 in A-flat Major, Opus 110

Sonata for Piano No. 32 in C Minor, Opus 111

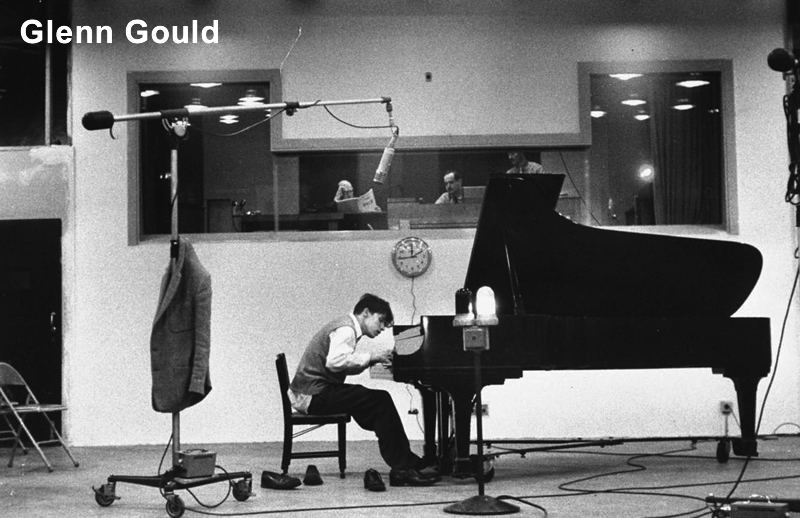

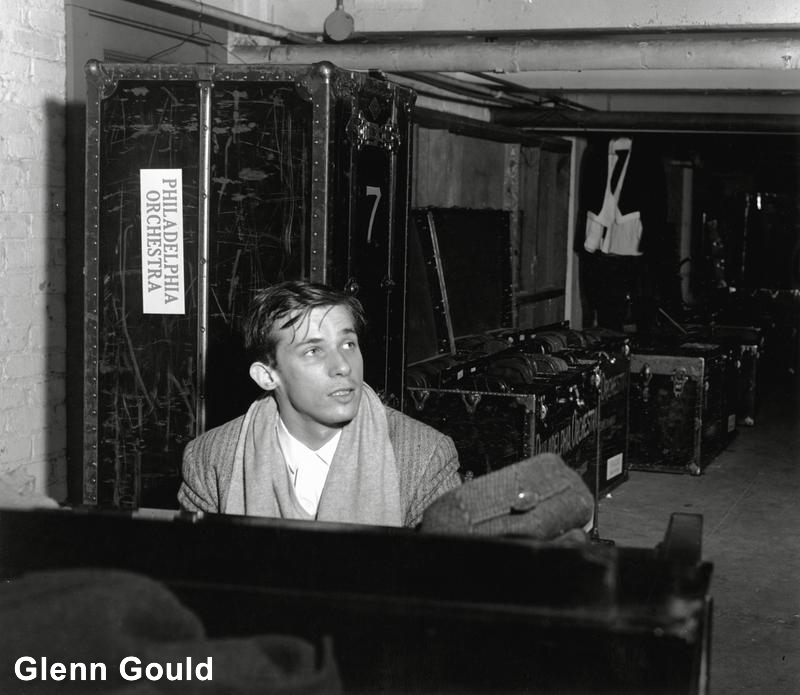

Glenn Gould, Piano

Recorded in 1956 (CBS Records)

ONE-SENTENCE REVIEW:

Beethoven is not the ideal composer for Glenn Gould (as Bach is – as illustrated here and here and here and here and here) but this is still a rousing, exciting performance throughout and, certainly, never boring.

ORIGINAL LINER NOTES (by Marc Vignal – translation by Robert Cushman):

To inaugurate at least two of the important periods of his career, Beethoven wrote a work of vast dimensions in the four traditional movements and applying Haydn’s principles of form on a scale hitherto unknown: on the one hand, the Eroica Symphony in 1804 and, on the other, the Hammerklavier Sonata (No. 29 in B-flat major, Op. 106) in 1818.

Only three piano sonatas – No. 30 in E major, Op. 109; No. 31 in A-flat major, Op. 110; and No. 32 in C minor, Op. 111 – were written after the Hammerklavier. They were composed between 1819 and 1822 in parallel with the Missa Solemnis, the other major work to which Beethoven was then devoting his time.

Only three piano sonatas – No. 30 in E major, Op. 109; No. 31 in A-flat major, Op. 110; and No. 32 in C minor, Op. 111 – were written after the Hammerklavier. They were composed between 1819 and 1822 in parallel with the Missa Solemnis, the other major work to which Beethoven was then devoting his time.

As for the Diabelli Variations, although they were started in 1819 before the last three sonatas, they were only completed in 1823, after a long interruption. The year 1823 was also that in which Beethoven did most of the work on the Ninth Symphony. After this there remained only the last five string quartets.

Compared with the Hammerklavier, the last three sonatas appear to mark a return to a certain brevity, even to a certain simplicity. All three are about the same length with, as a common characteristic, special importance given to the finale, which in each case lasts over half the length of the entire sonata.

Nevertheless, although Opus 109 has three movements and Opus 110 four, Opus 111 has only two. In themselves these overall structures were in no way extraordinary, but it is noteworthy that, in both Opus 109 and Opus 110, the section preceding the finale tends to be reduced to the role of an introduction.

The finales of Opus 109 and Opus 111 are in the theme-and-variations form, ending almost imperceptibly in silence (and yet they do not truly seem to end), while that of Opus 110 is a complex combination of recitatif, arioso and fugue (variations and fugues especially preoccupied Beethoven at the end of his life).

By comparison with what leads up to it, the finale of Opus 111 functions as an antithesis.

By comparison with what leads up to it, the finale of Opus 111 functions as an antithesis.

That of Opus 109 returns to and somehow prolongs the first movement (with the second movement acting as a violent interlude), while the finale of Opus 110 – the only one of the three to end fortissimo – little by little frees the energy previously held more or less in check.

Unlike the Hammerklavier and each in its own way, Opus 109, Opus 110 and Opus 111 are constructed in “open” form, and in them we remark a considerable simplification in style and in the working-out, as well as clearer alternations of tension and relaxation. Such alternations, however, are especially characteristic of the composer’s late works. In these sonatas Beethoven confronted time – and eternity.

Begun in 1819, Sonata No. 30 in E major, Opus 109 was finished in the autumn of 1820 but not published until November 1821, with a dedication to Maximiliane Brentano (the daughter of Antonie Brentano, whom Maynard Salomon believes the most likely candidate for the “Immortal Beloved”).

The manuscripts show that the first movement was originally planned as a separate piece, probably for inclusion in the future series of Bagatelles Op. 119. Of the last three sonatas this is the one that is most unlike the Hammerklavier, after which it offers a welcome feeling of relaxation.

The first movement presents a very free alternation of a lively theme (Vivace ma non troppo, sempre legato), of almost impressionistic sonorities, with an Adagio espressivo bearing the traits of an improvised recitatif. The Prestissimo in E minor (second movement) enters without a pause. The third movement (Andante molto cantabile ed espressivo), which returns to E major, opens with a calm, lyrical theme (a kind of sublimated sarabande) followed by six accelerating variations and closing with the repetition of the theme.

The first movement presents a very free alternation of a lively theme (Vivace ma non troppo, sempre legato), of almost impressionistic sonorities, with an Adagio espressivo bearing the traits of an improvised recitatif. The Prestissimo in E minor (second movement) enters without a pause. The third movement (Andante molto cantabile ed espressivo), which returns to E major, opens with a calm, lyrical theme (a kind of sublimated sarabande) followed by six accelerating variations and closing with the repetition of the theme.

Initially sketched in 1819 and completed by December 18, 1821, Sonata No. 31 in A-flat major, Op. 110 was published in August 1822, without a dedication. It begins with a Moderato cantabile molto espressivo which is undoubtedly the composer’s most beautiful lyrical movement, setting aside his slow movements. It offers resemblances with Schubert. There are many themes, but they follow one another smoothly.

Then comes a violent Allegro molto in F minor, a sort of scherzo in duple (rather than triple) time. After a normal organ point, everything forms a solid block, as Beethoven successfully performs the miracle of interlocking different opposites: arioso and fugue, profound despondency and elan vital. A solemn recitatif in B-flat minor (third movement or introduction to the finale?) marked Adagio ma non troppo opens this “universe of alternation” and culminates in an A repeated 26 times.

Then rises a song of lamentation (Arioso dolente) in A-flat minor leading to a fugue in A-flat major (Allegro ma non troppo) bringing a respite. When it falls away, the Arioso dolente comes back in G minor, more gasping, more despairing than ever. Ten increasingly powerful, obstinate G major chords try a new sally, and the fugue returns inverted and in G major (a distant key). This fugue is dropped once A-flat major reappears, thereby reinforcing the dramatic, triumphal effect of the final measures, especially since the piano writing here is particularly brilliant.

Then rises a song of lamentation (Arioso dolente) in A-flat minor leading to a fugue in A-flat major (Allegro ma non troppo) bringing a respite. When it falls away, the Arioso dolente comes back in G minor, more gasping, more despairing than ever. Ten increasingly powerful, obstinate G major chords try a new sally, and the fugue returns inverted and in G major (a distant key). This fugue is dropped once A-flat major reappears, thereby reinforcing the dramatic, triumphal effect of the final measures, especially since the piano writing here is particularly brilliant.

Completed in 1822 and published during the same year, with a dedication to Archduke Rudolph, Sonata No. 32 in C minor, Op. 111 has only two, completely dissimilar movements: minor and major modes, sonata form and theme-and-variations form, dynamic character and static character, dramatism and contemplation, etc.

It opens with an introduction (Maestoso) largely based upon diminished seventh harmonies. Three diminished sevenths follow one another and return in the same order as chords at the end of the Allegro con brio ed appassionato and, above all, as a generalized harmonic procedure during the central development.

This development is fugal: the main theme of the movement clearly called for a fugue, but Beethoven withheld using it earlier to provide increased animation in the development.

The second movement is the famous Arietta (Adagio molto, semplice e cantabile) in C major with variations. The theme is very simple, and the working-out moves toward constantly greater simplification – not in the musical or sound fabric, quite the contrary, but as regards the very conception of the theme, which is gradually reduced to a mere skeleton.

After about a quarter hour of the purest C major, we reach a cadential trill followed by a modulation to E-flat major: this passage constitutes the only harmonic motion in the movement and also the only passage in which, from the rhythmic standpoint, everything remains completely suspended, until the return of C major in the final, accelerated variations.

As Charles Rosen points out, Beethoven’s exploration, late in his life, of the tonal universe became more and more essentially meditative.

TRACK LISTING:

- 1-3: Beethoven Sonata for Piano No. 30 in E Major, Opus 109

- 4-6: Beethoven Sonata for Piano No. 31 in A-flat Major, Opus 110

- 7-8: Beethoven Sonata for Piano No. 32 in C Minor, Opus Opus 111

FINAL THOUGHT:

An 85 rating almost seems too low for ANY recording by Glenn Gould (he’s Glenn freakin’ Gould for goodness sake) but this entire recording is just so over the top intense that all subtlety is lost on the first notes of the first cut. But 85 out of 88 is still way better than most. I love Glenn Gould!

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company)

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company)