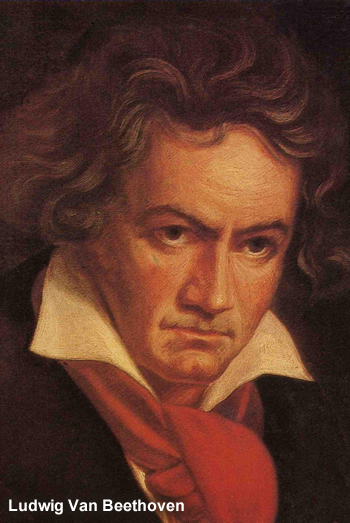

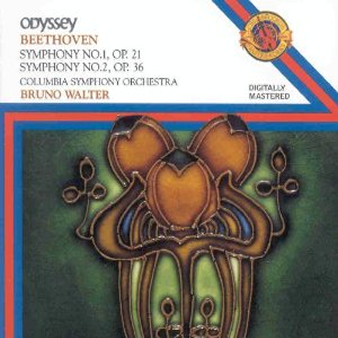

Ludwig Van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Ludwig Van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Symphony No. 1, Opus 21 in C Major

Symphony No. 2, Opus 36 in D Major

Columbia Symphony Orchestra (Bruno Walter, Conductor)

Recorded at American Legion Hall, Hollywood, California, 1959

ONE-SENTENCE REVIEW:

Now we’re getting into the meat – Beethoven Symphonies 1 & 2 – all I can say is Ludwig van is a talented man… the future looks promising.

ORIGINAL LINER NOTES (none):

Another budget disc from CBS Masterworks. They couldn’t even afford liner notes. But here’s a bit of info from our friends at Wikipedia:

SYMPHONY NO. 1

Ludwig van Beethoven’s Symphony No. 1 in C major, Op. 21, was dedicated to Baron Gottfried van Swieten, an early patron of the composer. The piece was published in 1801 by Hoffmeister & Kühnel of Leipzig. It is unknown exactly when Beethoven finished writing this work, but sketches of the finale were found from 1795.

The symphony is clearly indebted to Beethoven’s predecessors, particularly his teacher Joseph Haydn as well as Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, but nonetheless has characteristics that mark it uniquely as Beethoven’s work, notably the frequent use of sforzandi and the prominent, more independent use of wind instruments.

Sketches for the finale are found among the exercises Beethoven wrote while studying counterpoint under Johann Georg Albrechtsberger in the spring of 1787.

Sketches for the finale are found among the exercises Beethoven wrote while studying counterpoint under Johann Georg Albrechtsberger in the spring of 1787.

The premiere took place on April 2, 1800 at the K.K. Hoftheater nächst der Burg in Vienna.

The concert program also included his Septet and Piano Concerto No. 2, as well as a symphony by Mozart, and an aria and a duet from Haydn’s oratorio The Creation. This concert effectively served to announce Beethoven’s talents to Vienna.

SYMPHONY NO. 2

Symphony No. 2 in D major (Op. 36) is a symphony in four movements written by Ludwig van Beethoven between 1801 and 1802. The work is dedicated to Karl Alois, Prince Lichnowsky.

The Second Symphony was mostly written during Beethoven’s stay at Heiligenstadt in 1802, at which time his deafness was becoming more apparent and he began to realize that it might be incurable.

The work was premiered in the Theater an der Wien in Vienna on 5 April 1803, and was conducted by the composer. During that same concert, the Third Piano Concerto and the oratorio Christ on the Mount of Olives were also debuted. It is one of the last works of Beethoven’s so-called “early period”.

Beethoven wrote the Second Symphony without a standard minuet; instead, a scherzo took its place, giving the composition even greater scope and energy. The scherzo and the finale are filled with vulgar Beethovenian musical jokes, which shocked the sensibilities of many contemporary critics.

One Viennese critic for the Zeitung fuer die elegante Welt (Newspaper for the Elegant World) famously wrote of the Symphony that it was “a hideously writhing, wounded dragon that refuses to die, but writhing in its last agonies and, in the fourth movement, bleeding to death.”

TRACK LISTING:

- 1-4: Symphony No. 1, Opus 21 in C Major

- 5-8: Symphony No. 2, Opus 36 in D Major

FINAL THOUGHT:

Regardless of what Wikipedia, above, says – I think Symphony No. 1 is clearly a “Beethoven” symphony” and not as indebted to his predecessors (unless we’re talking about length) as others may believe. And no matter how many times I listen to Symphony No. 2, I just don’t get the “hideously writhing, wounded dragon…” It’s just not that violent (but I’m sure that joke killed at the Biergarten after the concert).

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company)

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company)