Borodin – String Quartet No. 1 in A

Borodin – String Quartet No. 2 in D

Borodin String Quartet (Mikhail Kopelman – violin; Andrei Abramenkov – violin; Dmitri Shebalin – viola; Valentin Berlinsky – cello)

Recorded in 1980 by Melodiya in the USSR (Released in the US by EMI in 1987)

ONE-SENTENCE REVIEW:

It was “Kismet” that full-time scientist and part-time composer Alexander Borodin should write these exquisite string quartets! (see what I did there?)

ORIGINAL LINER NOTES (by John Warrack, 1982):

When Tchaikovsky and Borodin wrote their string quartets in the 1870s – Tchaikovsky’s three between 1871 and 1878, Borodin’s first between 1873 and 1879 – they were entering virgin territory.

Though both had written a good deal of chamber music as young men, these works were for the most part either student efforts or pieces conceived in a fairly unassuming manner for amateur entertainment.

The Russian string quartet, as a genre, did not exist. There were previous attempts – even Glinka completed a quartet, though he did not think much of it – but in Russian musicians’ endless debates on the course their art should take, the quartet did not play a large part.

The Russian string quartet, as a genre, did not exist. There were previous attempts – even Glinka completed a quartet, though he did not think much of it – but in Russian musicians’ endless debates on the course their art should take, the quartet did not play a large part.

The foundation of the Russian Musical Society in 1859 gave an enormous impetus to Russian musical life. Chamber music featured in the Society’s programmes; and new interest in the string quartet followed upon the founding of the Russian String Quartet in 1871.

Its members were Panov, Leonov, Yegorov and the young cellist, later to be a distinguished figure in Russian musical life, Alexander Kuznetsov. Tchaikovsky described them in 1874 as ‘an ideally harmonious ensemble.’ Other players, in St. Petersburg and Moscow, formed more or less regular ensembles; and the effect was to increase rapidly the appreciation and understanding of the classics of Western string quartet music among Russian musicians.

However, Russian composers were concerned to develop their own methods, rather than model themselves slavishly on Western example. More than the virtuoso French quatuor concertant tradition, it was to the Viennese tradition that they turned, despite the natural Russian affinity for Latin rather than Teutonic art; but when Borodin began work on his first quartet, he was clearly anxious to find structural methods that were more identifiably Russian.

The use of folk music, or melodies close to the Russian folk manner, was one immediate stimulus; but Borodin did not associate himself with the so-called Slavophiles, the more vigorously nationalistic of the Russians, and indeed when he showed his first sketches of this quartet to Mussorgsky and the critic Stassov, they were ‘horrified,’ he said.

He may have begun work as early as 1873-4; the sketches were ready by April 1875, more substantial work was done during a happy summer in 1877 in the country, and the quartet was finally completed, with the scherzo, in early August 1879.

He may have begun work as early as 1873-4; the sketches were ready by April 1875, more substantial work was done during a happy summer in 1877 in the country, and the quartet was finally completed, with the scherzo, in early August 1879.

The slow gestation can be partly explained by the fact that he was also working on Prince Igor (to which there are some thematic resemblances), also perhaps by the problems of building a novel work in a non-existent tradition.

The first performance, by the quartet of the Russian Musical Society (which had by now changed some of its members) was in St. Petersburg on December 30, 1880; it was a success, the players declaring that they were ‘simply delighted’ with the work.

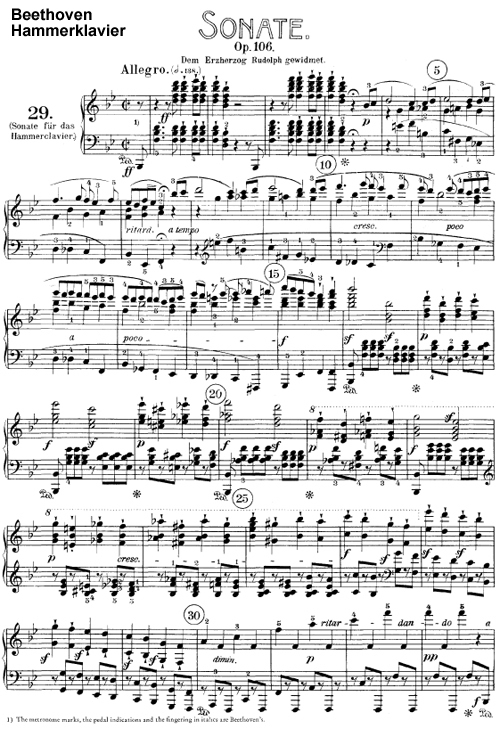

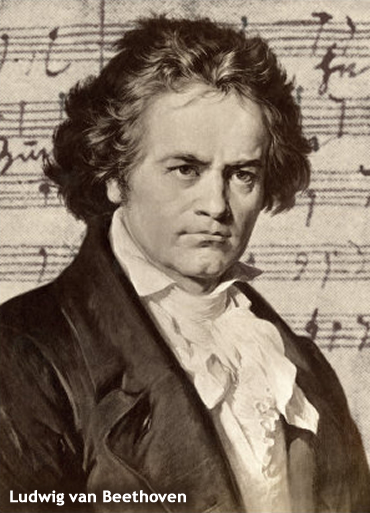

Borodin’s attachment to classical practice led him to keep to the traditional sonata form structure for his first movement; and indeed after a moderately slow introduction, the first subject of the movement is actually based on a theme by Beethoven.

In admitting this, Borodin did not identify the theme: it is in fact from the finale of the B-flat Quartet, Op. 130. However, the handling of the theme is in no way like Beethoven: the flowing melody is passed around the two violins and the cello with variants of its basic form.

This varied repetition was a device much admired by Russian composers in Glinka, and in many different ways used as the substance of large-scale movements, but Borodin’s handling is unusually free and subtle

It leads to a second subject also in freely-flowing quavers, at first over a shifting drone bass; and only towards the close of the exposition does the music reach any real tension, in the wake of a fugue initiated by the cello. After the recapitulation, the movement ends quietly with a long mysterious coda.

With the Andante, Borodin turns openly to a more folk-like manner, and even, it seems, to an actual folk tune. At the time he wrote the movement, 1874-5, he was helping Rimsky-Korsakov with gathering material for his Collected Russian Folk-Songs; and a song that particularly attracted him in one of the anthologies they searched, Vassily Prokunin’s Russian National Songs (1872-3), was ‘The Song of the Sparrow Hills.’

With the Andante, Borodin turns openly to a more folk-like manner, and even, it seems, to an actual folk tune. At the time he wrote the movement, 1874-5, he was helping Rimsky-Korsakov with gathering material for his Collected Russian Folk-Songs; and a song that particularly attracted him in one of the anthologies they searched, Vassily Prokunin’s Russian National Songs (1872-3), was ‘The Song of the Sparrow Hills.’

Borodin used a version of it in Prince Igor, on which he was simultaneously working, and, beginning with the viola counterpoint to the opening tune, the whole Andante is permeated with variants and reminiscences of the song.

Borodin’s biographer Sergey Dyanin, who studies these correspondences in detail, suggests that the course of the movement is also colored by the words of the song. This concerns an eagle holding in his talons a crow which tells him of a young hero he has seen lying dead, while over him hover three pipits that are his mother, his sister and his wife.

If we wish to follow this idea, the first theme may be associated with the eagle and the crow, the fugato with the pipits, the impassioned ending with their grief.

Dyanin goes further and suggests associations with an imagined story of the young hero: there is no justification for this beyond Borodin’s known liking for background programmes, nor any reason to regard the lively Scherzo and Trio as anything but a brilliantly assured contrast to the somber mood of the Andante.

For the finale, Borodin returns to sonata form, once again prefacing it with a brief introduction. As before, there is a stronger emphasis on sustaining the movement’s considerable momentum by means of varied repetition, and insistence on the driving rhythms, than on any development in the manner of Beethoven.

By contrast with this work, Borodin’s second, and much better known, quartet was written in a short space of time, during a contented summer in the country at Zhitovo.

By contrast with this work, Borodin’s second, and much better known, quartet was written in a short space of time, during a contented summer in the country at Zhitovo.

Increased assurance, rather than this burst of creativity, should perhaps be given credit for the quartet’s greater unity, not only of mood but also in thematic handling. Thus, there already appears in the first subject a dactylic figure (a long and two short notes) which the listener is clearly intended to recall when it occurs more prominently in the second subject.

These two related themes are the substance of the movement’s progress through the traditional exposition, development and recapitulation; but Borodin produces two other fragments of themes – they are scarcely more than figures of four bars each – which serve to shed contrasting emotional light on the main pair of themes.

The Scherzo is no less ingeniously put together. Perhaps Borodin thought it difficult to handle a traditional Scherzo-and-Trio in times so far removed from the Scherzo’s dance origins in the Minuet; but he acknowledges the connection by answering his fleeting, almost Mendelssohnian first theme with what is virtually a waltz. These are then made the material of a brief sonata movement.

After the famous Nocturne – a movement much abused by arrangers, and with its ravishing, somewhat oriental tune best presented as Borodin intended – the finale opens with a brusque, Beethovian gesture of question and answer.

Essentially, it is based on the rapidly and ingeniously varied treatment of these two themes (they immediately turn out to work together fugally) and a contrasting second subject. If the repeated question-and-answer interruptions suggest some private references, what matters to the listener is a skillfully and satisfyingly constructed finale, most original in form, to a brilliantly original quartet.

TRACK LISTING:

- 1-4: String Quartet No. 1 in A Major [36:51]

- 5-8: String Quartet No. 2 in D Major [28:53]

FINAL THOUGHT:

Methinks Mr. John Warrack is a bit of a snob in his notes. If you write CD notes about Borodin’s String Quartet No. 2 and fail to mention that some of the melodies became the foundation of a popular Broadway musical (“Kismet” – he even won a posthumous Tony Award!) and an incredibly beautiful popular ballad (“And This Is My Beloved”) and instead just say the quartet has been “abused by arrangers” – you are probably a bit of a music snob. For the most part, nobody would have even heard of Borodin if it wasn’t for “Kismet.”

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company)

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company)