Anton Bruckner (1824 – 1896)

Symphony No. 3 in D Minor – “Wagner”

———————

Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Conductor

Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra

Recording Location: Het Concertgebouw, December 1994 – Live Recording

———————

ONE-SENTENCE REVIEW:

Now we’re talking!

ORIGINAL LINER NOTES – “Anton Bruckner: An Antenna Pointing Into The 20th Century” – Nikolaus Harnoncourt In Conversation With Walter Dobner

W.D.: According to one 19th-Century review of the Third Symphony, “Bruckner has his moments -flashes of imagination of a kind found only with great men on genius – but they are soon past.” I don’t suppose you share this view, Herr Harnoncourt?

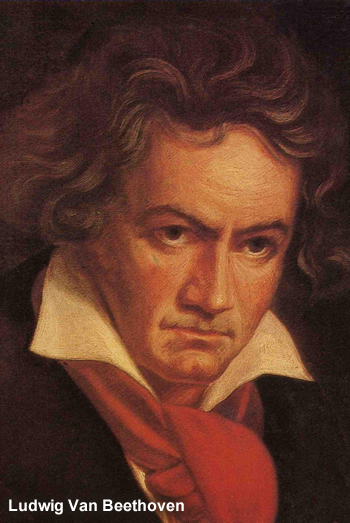

N.H.: Not for a moment. But nor do I share the view of contemporary critics of Beethoven’s Second Symphony. None the less, there’s some truth in the suggestion that a transcendent genius like Bruckner – or any other great composer for that matter – positively invites disapproval and criticism. You can’t expect people to agree completely with such music.

The whole meaning of a work is revealed only by contradiction. It’s only when you ask what happens between these flashes of genius that you may find a lot happening that may not appear so brilliant after all.

There was a time when I myself saw Bruckner in this light. I felt I was returning home from a Bruckner symphony with a relatively small number of very important discoveries. But the symphonies were too great for that.

Today, I’ve changed my mind completely, since I now understand much better what this music is all about.

W.D.: Can you say in a few words what you mean by that?

N.H.: The experience I had with Bruckner was similar to the one I had with Beethoven. I initially had great problems with the finale of both the Ninth Symphony and Fidelio. They struck me as too distended and, in consequence, as seriously lacking in substance. Only later did it become clear to me that I was approaching this music with the wrong standard.

In the case of the Missa solemnis I suddenly saw that it was simply absurd to judge Beethoven by Mozart’s standards. Beethoven makes other demands , asks other questions and so he got other answers. As soon as I set aside my “Mozart” yardstick and found one that seemed to me better suited to Beethoven, I suddenly discovered a whole new approach to his works.

Exactly the same thing happened with Bruckner. The more I got to know Brahms, the more precious Bruckner became. It was presumably the great effort and seriousness of Brahm’s writing that produced such wonderful results after years of polishing and honing and that led me to his antithetical opposite, Bruckner, bringing him closer and closer to me.

W.D.: Is Bruckner not also so difficult to understand because there are so many different links? Although his music speaks the language of the 19th century, it is also deeply indebted on a formal level to the Classical 18th century, to say, nothing of the gestures – and mysticism – of the Middle Ages.

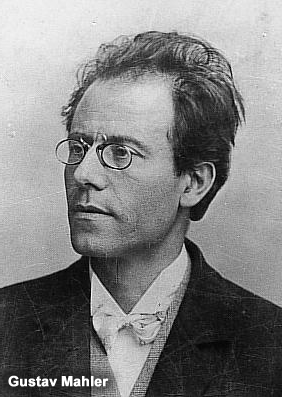

N.H.: Curiously enough, Bruckner strikes me – far more than any other composer of his generation – as someone with an antenna pointing into the 20th century. When people claim that it was Mahler who laid the foundation of the Second Viennese School, I have to say that this seems to me to have been even more true of Bruckner – not that I would want to disagree with any of the criteria you’ve listed.

Those aspects that go back to the Middle Ages are presumably tied up in some way with Bruckner’s markedly rustic character. But I don’t think it’s possible to approach his works from a biographical standpoint. If you were to start out from Bruckner’s personality, you’d expect to find extreme conservatism in his works. But his visions really can’t be squared with his simplicity as a person. In this respect, he is unique as a genius.

W.D.: But is it really possible to draw a total distinction between Bruckner as a person and Bruckner as a composer? Shouldn’t the thematic triality of his symphonic movements be seen not only as a symbol of the Trinity but also as evidence of Bruckner’s personal faith? What are your thoughts on this and on the theory that only a believer can interpret Bruckner?

N.H.: I don’t think faith comes into it. Anyone who performs Bruckner needs to be familiar with Austrian music, with Schubert, with peasant music and the whole ländler thing. I wouldn’t dare try to find evidence of Bruckner’s religious beliefs in the symbols of his music.

It may well be that these signs of personal belief does exist, but biographers, exegetes and musicologists who explain this only on the basis of the works, without the composer’s say so, are guilty, I believe, of venturing into a highly dangerous and highly speculative area.

For me, Brucker’s symphonies are couched in a language of musical sounds that is his very own, personal language. That his personality was very strongly influenced by his faith is sufficiently well attested. Whether his music would sound different without this pronounced religious influence, I don’t think any of us can say. But I think it’s far too simple as an explanation to derive this thematic triality from the Trinity.

W.D.: The ‘Musician of God,’ is only one of many Brucknerian cliches. Bruckner is also sometimes regarded as a typically Austrian composer. It’s argued that he takes his place in a line beginning with Schubert and leading to Mahler and, finally, to Schoenberg.

N.H.: I’d describe only highly concrete details of his music as typically Austrian, for example, the Trios in his Scherzos and a few melodic ideas that I associate with Bruckner’s rustic origins or with elements of Austrian folk music.

With Schubert, it’s totally different – he could only be Austrian, his music speaks Viennese dialect. The line of development that starts out with Schubert certainly leads in Bruckner’s general direction, but it actually goes, rather, to Johann Strauss; that’s pure unadulterated Austrian music for you.

There seems to me a very clear line of development from Bruckner to the Second Viennese School, especially to Alban Berg, rather less so to Schoenberg, although Schoenberg often transcribed Strauss.

I’m happy to leave out Mahler – he’s really not conceivable without Bruckner. I regard Bruckner’s music as absolute. The autobiographical element in his music isn’t all that marked. Unlike Mahler, who uses Bruckner’s vocabulary, Bruckner does not retell his own life in a superficial way. I see a basic difference between a composer who sees himself as the agent of his talent and one who uses the vocabulary of a composer like Bruckner in order to tell us all about his private sufferings.

W.D.: Herr Harnoncourt, you say that Mahler is inconceivable without Bruckner. Is Bruckner conceivable without Wagner?

N.H.: Certainly. The links between Bruckner and Wagner must have been in the air at the time. You can already hear Wagner and Tchaikovsky in a number of Mendelssohn’s works – I’m thinking of Die erste Walpurgisnacht and Die schöne Melusine. Virtually the whole of the 19th century is contained in these works.

One has the feeling that if Mendelssohn had had a normal lifespan, Wagner would have been inhibited by such proximity. I don’t think there is anything in Wagner’s musical language that wasn’t already part of the spirit of the times. Wagner had to exist in the 19th century. Bruckner had to exist as a writer of symphonies, not as a music dramatist. The fact that Bruckner revered Wagner I see as a sign of his modesty.

W.D.: Herr Harnoncourt, you’re beginning your explanation of the world of Bruckner’s symphonies with his Third Symphony, of which there are three different versions. Why did you opt for the second version?

N.H.: The final version was ruled out for me on account of its excessive cuts and excisions that almost destroy the work’s organic unity. For me, it’s a makeshift solution designed to keep the symphony in the running, as it were.

The first version is very complex and rambling, with a lot of Wagnerian quotations. I could well imagine conducting this first version after extensive preparation. I see the second version as the result of Bruckner’s wrestling with the first one. Also, I think that the coda to the Scherzo provides a very interesting and convincing ending here. I think Brucker knew perfectly well how he imagined his works would sound and that he set this down quite clearly.

He said: “My work is in the score.” But although he worked on the score, he did not – so to speak – prepare it in bite-sized morsels. The versions that various friends and conductors forced out of him were concessions to these friends and to audiences, prompted by the wish to be performed at all.

W.D.: And which edition of this symphony did you decide to use for your own performance?

N.H.: I’m conducting the second version in Nowak’s edition, since it’s the one I find most convincing. You must never forget that fashion plays an important part here, too. Now that we’re familiar with Nowak’s versions, we know how he arrived at his findings. The sources are available.

Of course, one could now try reaching one’s own conclusions and results on the strength of the sources. That’s the prerogative of every generation. I trusted Nowak more than I normally trust editors and haven’t reexamined every question on the basis of the sources in order to make my own decisions, but compared the various findings of the individual editions.

I also consulted an edition from the Concergebouw Orchestra, with whom I made this recording, since I also wanted to learn more about this orchestra’s tradition.

W.D.: Not only the Royal Amsterdam Concertgebouw Orchestra can look back on a long tradition of performing Bruckner, so, too, can the Vienna Symphony Orchestra, with whom you began your career as a musician. They, too, have considerable experience of playing Bruckner’s works. To what extent was this knowledge of the performing tradition of use to you during your present involvement with Bruckner, or did you fell inhibited by it?

N.H.: These experiences were of great use to me and certainly didn’t inhibit me. The older I get, the more natural Bruckner’s musical language seems to me. I feel at home here, it’s the element in which I live and breathe. I can recall some very great performances of Bruckner while I was a cellist with the Vienna Symphony Orchestra.

I’m thinking in particular of Karajan during the 1950s. I’d be interested to hear those performances again and would like to know whether my experience at that time – I’d not yet turned thirty – would stand up to my present understanding. But they left an indelible impression on me.

In the case of the present performance, it was important for me to work with an orchestra that knows and understands Bruckner’s language. At the same time, of course, I had to fight against this experience at rehearsals, since there are certain passages that are interpreted in identical ways by virtually every conductor.

I’m thinking, for example, of the decelerandos, especially in the slow movement of the Third Symphony; the answers in the orchestra are almost always taken twice as slowly as the questions. There isn’t the slightest indication in the score that this is how these passages should be taken. And yet orchestras are used to playing them like this.

But when a composer like Bruckner writes even the tiniest change of tempo into the score and when he prescribes even the least expressive nuance by means of footnotes and explanations, I’m tempted to agree with him and included to clear away all this ballast.

________________________________________-

Within twenty-four hours of his meeting with Wagner in Bayreuth in September 1873, Anton Bruckner could no longer remember whether the Master had accepted the dedication of his Second or Third Symphony.

Remarkable though this lapse must seem, contemporary accounts make it plain that Bruckner’s uncertainty was due not so much to his awesome encounter with a man whom he revered as “the master of all masters” as to the vast amounts of beer that he and Wagner had consumed.

With his memory of this historic encounter decidedly befuddled, Bruckner sent the older composer a note in an attempt to resolve the matter. “Symphony in D minor, where the trumpet begins the theme?,” he asked, to which Wagner appended his reply: “Yes, yes! Best wishes!”

The first draft of the score was completed by the end of the year, and Cosima Wagner confirmed receipt of the dedication copy on June 24, 1874. Shortly afterwards, Brucker offered his new symphony to the Vienna Philharmonic, but the orchestra rejected the piece after a trial run-through in the autumn of 1875.

As with so many of Bruckner’s works, the original version of the score proved only the starting point of a whole series of major revisions.

The ink on the dedication copy was scarcely dry before Bruckner had already set out to make ‘significant improvements to the Wagner Symphony (in D minor),’ to quote from a letter to Moritz von Mayfeld, but the result was not yet an independent version, for this, we have to wait until the thoroughgoing version of 1876/77, when Brucker added the ‘Adagio No. 2′ (1876) and produced an intermediate version that occupies a halfway house between the first and second versions. (As a result, there are a total of four versions of the slow movement – something of a rarity in the history of music – and three different versions of the symphony as a whole.)

On April 28, 1877, Bruckner finally added a note to the concluding movement ‘entirely new revision finished.’ The second version, Bruckner though, was now complete.

The work was premiered in this form in December 1877 and, notoriously, proved a failure. But Bruckner refused to be daunted and in January 1878 made a further series of changes to this second version, including the addition of a coda to the Scherzo. The second major revision dates from 1888/89, when Franz Schalk played a decisive role and incurred the charge of ‘foreign interference’ in the score. In this revised form the work found favor with its audiences.

The question of “failure” and “success” lead us straight to the heart of the problems surrounding the different versions. To a certain extent we are dealing here with “improvements” designed to accommodate the work to audience expectations. There is no doubt that Bruckner craved success and constantly sought recognition, avidly reading reviews. It is difficult to avoid the suspicion, therefore, that it was only those works that had proved an initial failure that were subjected to a process of revision, either by Bruckner himself or by others.

(It is surely significant in this context that the Seventh Symphony, with which the composer made his international breakthrough, was left untouched.) Legion are Bruckner’s remarks reflecting his conformist outlook and his willingness to make concessions.

In consequence, the various versions are assessed in different ways by musicians and scholars. For some, the principal aspect is the process of improvement, whereas others acknowledge the independence of each individual version.

It is important to realize that the changes should not be approached from a purely qualitative standpoint but must be examined in the light of the circumstances that produced them and the period at which they were made. Give the length of time that Bruckner devoted to the Third Symphony – a total of sixteen years – it would perhaps be more appropriate to speak of a ‘work in progress.’

In what ways do the three versions differ? This question is normally answered by reference to cuts, although this affects only one, albeit important, aspect. A comparison of the overall length of the symphony in all three versions reveals that, whereas the first version is 2056 bars long, the second runs to 1815 bars and the third is 1644 bars in length. But even here we must proceed with caution since the cuts do not affect all the movements equally. The Scherzo is the exception to the rule inasmuch as it is eight bars longer in the second and third versions.

Further changes affect the structure of the musical periods, a process that Bruckner himself called ‘rhythmic ordering.’ In the transitions he strove to achieve a greater interweaving of the motifs, with denser textures in the long ascents to climaxes that so often fail to materialize.

He also altered the accompanying figures and instrumentation. In the case of the Third Symphony, there is also the question of Bruckner’s collage-like use of fifteen Wagnerian quotations, the vast majority of which had already disappeared by the time of the second version, a change no doubt dictated by the composer’s wish to reduce the work’s powerfully subjective content and, at the same time, emphasize its autonomy.

The second version is closely tied up wit the Concertgebouw’s Brucknerian tradition; the Third Symphony was the first of the composer’s symphonies to be played by the Amsterdam orchestra, when Willem Kes conducted a performance on October 13, 1892.

In 1897, Willem Mengelberg conducted the local premiere of the Fourth Symphony, and the Ninth was introduced to Amsterdam audiences in 1908. A period of particularly intense interest in Bruckner began with Eduard van Beinum, who was appointed the Concertgebouw’s second conductor in 1931 and who once said of the composer: ‘Bruckner is my daily bread. I can never get enough of his music.’

Many outstanding performances of Bruckner’s symphonies too place under van Beinum’s baton, although they continued to be based on the seriously deficient first editions of the scores. Only slowly was Robert Haas’s old Bruckner Edition of the 1930s adopted.

In the sixties, Eugen Jochum and Bernard Haitink showed themselves to be Brucknerians of the first rank. While Jochum soon came to prefer Nowak’s new edition, Haitink remained loyal to Haas. Haitink was succeeded in 1988 by Riccardo Chailly, who has continued the Concertgebouw’s longstanding – and outstanding – Bruckner tradition.

Erich W. Partsch

_______________-

TRACK LISTING:

Anton Bruckner (1824 – 1896) – Symphony No. 3 in D Minor – “Wagner”

- Gemäßigt, mehr bewegt, misterioso – 19:29

- Andante: Bewegt, feierlich, quasi Adagio – 13:26

- Scherzo: Zeimlich schnell – 7:02

- Finale: Allegro – 14:37

FINAL THOUGHT:

Insanely long liner notes not withstanding, Bruckner’s Third Symphony is the one that turned the world in favor of Bruckner. And, thank God. If Bruckner’s 6th didn’t exist – it would have really sucked.

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company