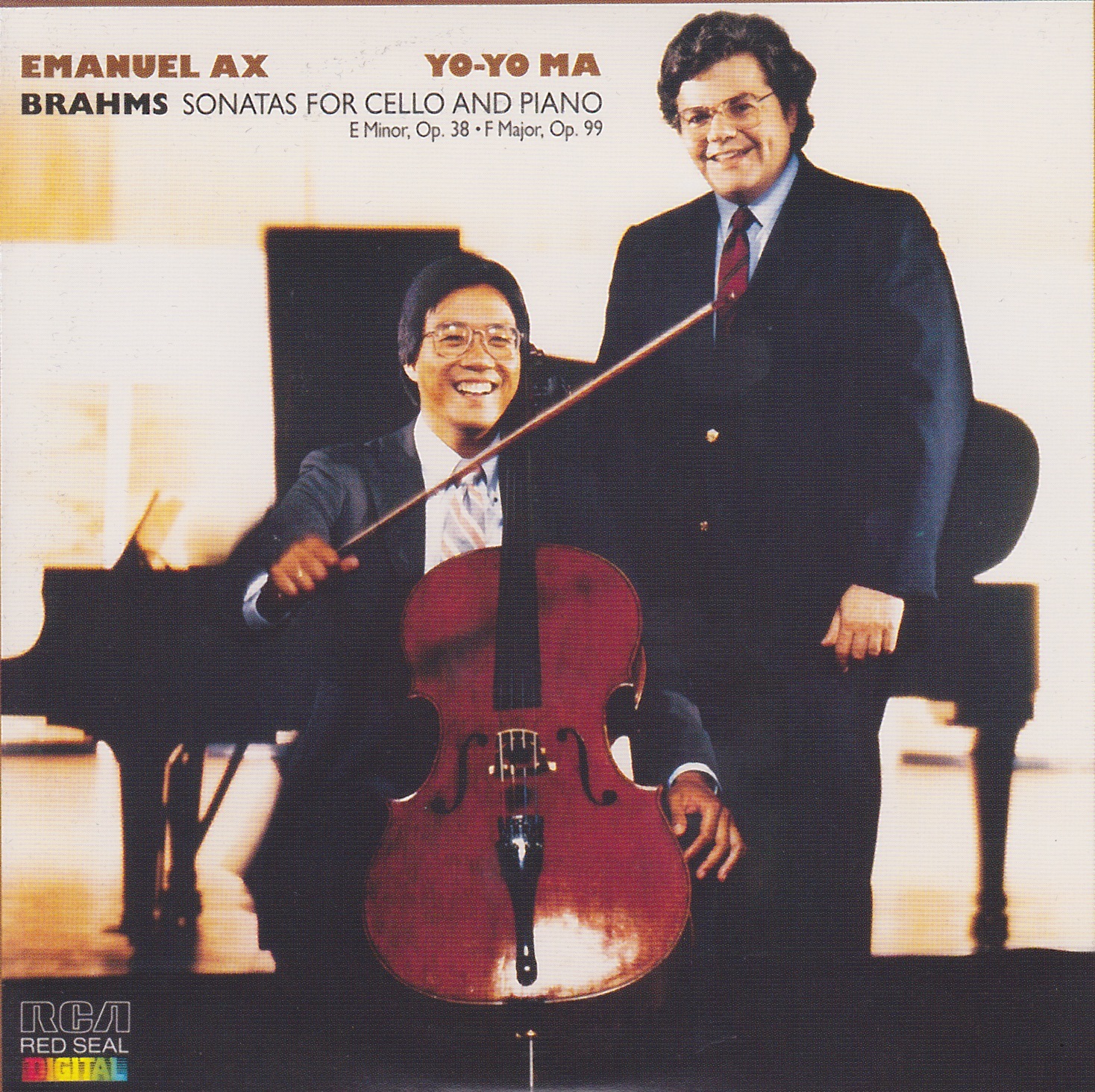

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897)

Sonatas For Cello and Piano

Produced by Jay David Saks

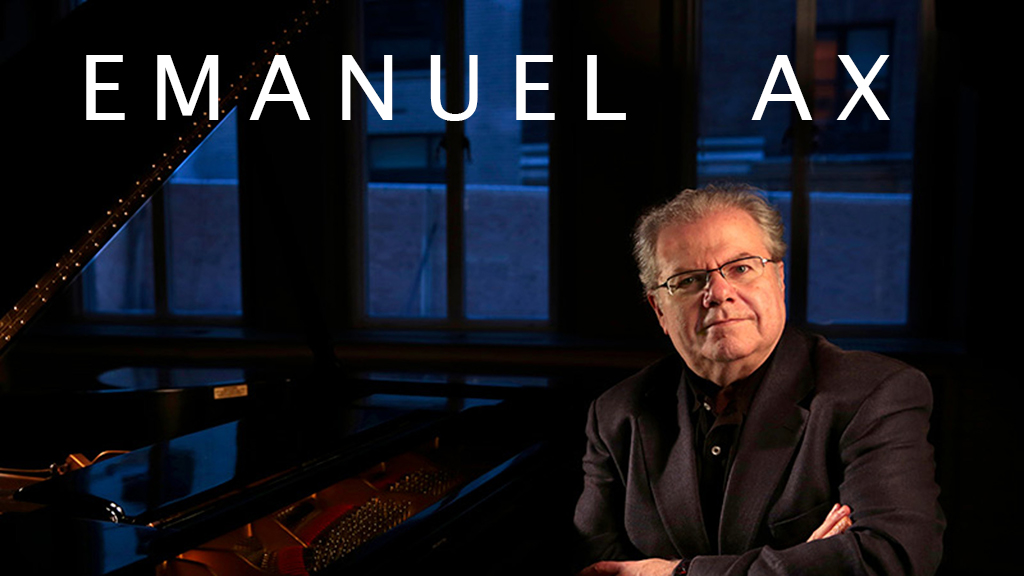

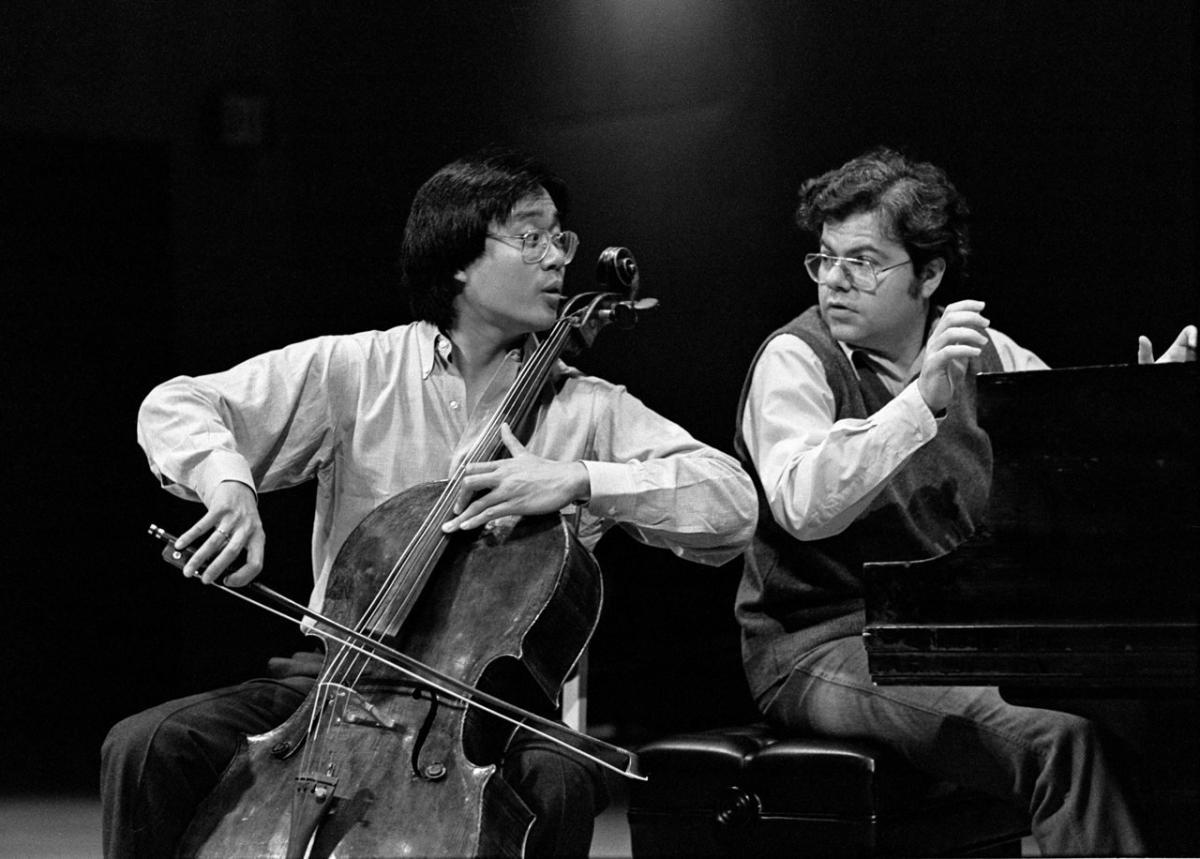

Yo-Yo Ma – Cello

Emanuel Ax – Piano

Recording Date: February 4 & 5, 1985

Recording Location: RCA Studio A, New York City

ONE-SENTENCE REVIEW:

Yeah, um, no – there is nothing to say other than Yo-Yo Ma and Emanuel Ax play Brahms.

ORIGINAL LINER NOTES (Bernard Jacobson, 1985):

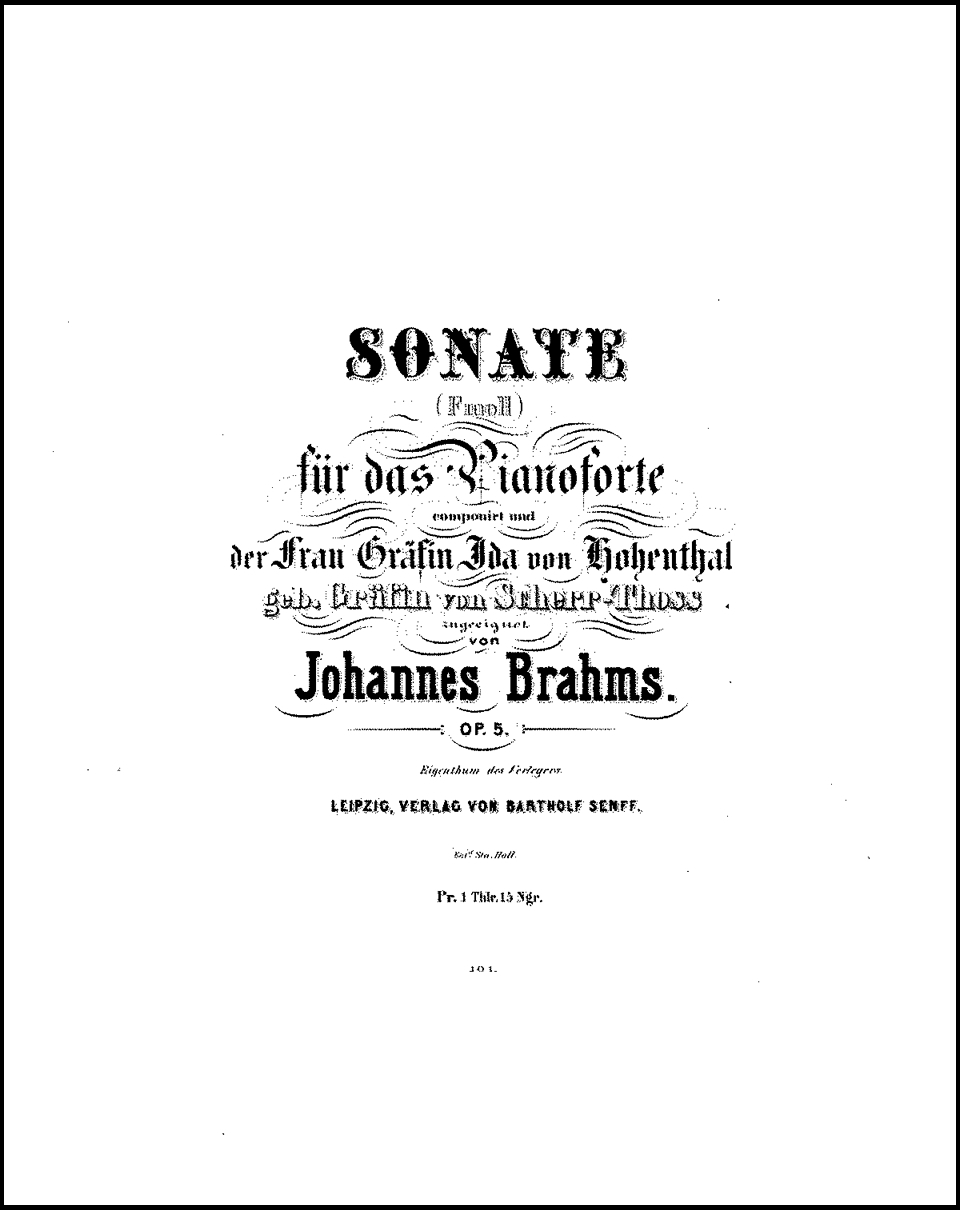

Opus 38 is not merely the first of Brahms’ cello sonatas: it was the first sonata he published for piano with any other instrument. The three surviving violin sonatas came much later and the two for clarinet later still.

Apart from early essays that the fiercely self-critical composer destroyed, including a duet for cello and piano that he played in public when he was 18, the E minor sonata’s only partial predecessor was the C minor scherzo (or Sonatensatz) he contributed in 1853 to a composite sonata written jointly with Schumann and Albert Dietrich as a tribute to the great violinist Joseph Joachim.

If you think about the character of Brahms’ music throughout his life, and in particular about the qualities of color and texture that make it unmistakably Brahms, it is not surprising that, in 1865, he should have approached the chamber-sonata medium through the cello.

The idea that Brahms was indifferent to instrumental color is a misapprehension. The truth is, surely, that he was relatively uninterested in the more obvious and dazzling instrumental effects.

Consider, for instance, his extraordinary use of the piccolo in the Tragic Overture. This usually obstreperous instrument appears in only 15 of the work’s 429 measures – and then exclusively in mysterious pianissimo.

Rather than brilliance, it was warmth of tone that attracted Brahms. And thus it is the clarinet and the horn that he most favors among the woodwind and brass families, and the cello among the strings. In all four symphonies some of the most memorable string effects are those entrusted to the cellos.

Then there are notable solo passages like those in the slow movement of the Second Piano Concerto, not to mention the wonderfully idiomatic handling of the cello in the Double Concerto, where it not only shares the limelight with the traditionally more extrovert violin but often takes the leading role in thematic exposition.

Following this line of thought, we find also that nobody, probably, has ever written a more cello-ish cello sonata than Brahms’ E minor. Through the entire length of the work (written for and dedicated to his friend Dr. Joseph Gansbacher) it is the special dark, introspective quality of the instrument that is stressed.

The very first theme exploits its ability to sing a sonorous melody in the lowest register, and at no point in the three movements does the pitch of the cello writing rise high enough to demand the use of the treble clef.

Tone color aside, the E minor sonata is Brahmsian also in reflecting its composer’s Janus-like relation to music history. Brahms faced equally in two directions: toward the past, and toward the future.

Much of his influence on later music derives from the linear and rhythmic freedom of his style, which was to have an effect at least as far reaching as – and arguably healthier than – that of Wagner’s innovations in the harmonic sphere. But Brahms’ liberation of line and pulse, though new to the 19th century, stems from his enthusiasm for the music of a much more distant past, going back to the time of Palestrina and indeed beyond that to the earliest origins of German song.

With all its freshness of expression, this sonata has a certain almost self-consciously old-fashioned air. In the first movement, it is to be found in the unhurried deployment of traditional sonata-form elements, and, more intangibly, in the kind of legendary, “far away and long ago” feeling to the actual cut of the themes.

The other two movements are more specifically historical in reference, the one recalling the minuet style, the other adopting fugal patterns, and the two together constituting a pair of genre pieces evocative of the baroque sonata or suite.

Yet, even here, the backward look is closely related to a forward influence. It is movements like this quasi-minuet that furnish the clearest link between Mahler’s folkish Knaben Wunderhorn vein and its medieval antecedents, and indeed the contrast of idioms between Brahms’ first two movements suggests a peaceable juxtaposition of past with present and future styles much like that of the corresponding movements in Mahler’s Second Symphony.

As Brahms matured, he turned away from formal displays of fugal erudition like those in the E minor sonata’s finale, the Handel Variations for piano and German Requiem, and instead began to fuse the forms and harmonies of his sonata style more intimately with its contrapuntal elements.

Certainly the finale of the F major cello sonata, written in his Swiss summer retreat at Thun in 1886, wears its learning more lightly than its youthful predecessor. But formidably learned this sonata still is, whether in the polyphonic play and pitting of three groups against duple meter in the finale, or in the subtle rhythmic elisions of the scherzo, or in the piano’s breathtaking pp dolce augmentation of the main theme just before the end of the first movement’s development section.

It is not so much learning, however, as passion that strikes the listener first in this deceptively youthful music. The very beginning of the Allegro vivace immediately proclaims the contrast with the E minor sonata: here all is full-blooded romanticism, felt in the constant tumultuous undermining of the movement’s official 3/4 pulse, and articulated as early as the seventh and eighth measures by the devil-may-care leap to the cello’s topmost register.

If the older Brahms tended more and more to moderation, this sonata is a glorious exception, as the “vivace,” “passionata” and “molto” of its movement-headings already suggest. Perhaps, as in the Double Concerto written the following year, it was the return to his old love of the cello combined with the inspiration provided by the gifted young cellist Robert Hausmann that prompted this resurgence of expressive ardor.

It is evident also in the plangent pizzicatos and subsequent Klangfarben-like coloristic effects of the Adagio affettuoso and in that movement’s remote and Haydenesque setting in the flat supertonic key of F-sharp major.

A tangible link with the Double Concerto, incidentally, is to be found in the transition theme of the sonata’s first movement, which could almost be regarded as the concerto’s slow-movement theme set at a different melodic angle.

But the superb coup just before the movement’s end – this time a purely harmonic device that transmutes the last, literal restatement of the stirring subordinate theme into a tender valediction – is a stroke of genius that is all the sonata’s own.

TRACK LISTING:

Johannes Brahms – Sonata For Cello And Piano No. 1 In E Minor, Op. 38

- Allegro non troppo – 14:43

- Allegretto quasi Menuetto – 5:58

- Allegro – 6:37

Johannes Brahms – Sonata For Cello And Piano No. 2 In F Major, Op. 99

- Allegro vivace – 9:22

- Adagio affettuoso – 7:45

- Allegro passionato – 7:20

- Allegro molto – 4:32:

FINAL THOUGHT:

Imagine you’re a cellist and a pianist and you’re trying to do some Brahms in your spare time and then freakin’ Yo-Yo Ma and Emanuel Ax come out and just stick the landing like it’s never been stuck before. That’s this recording!

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company)

Emily Sachs – President – Manka Music Group (A division of Manka Bros. Studios – The World’s Largest Media Company)